No matter how painful it can be, these shows make me grateful to love television and excited to be a superhero fan.

I can’t wait for the next five years.

When I last set out to survey the landscape of superhero television, figuring out where to start was easy. Arrow debuted in October 2012 and kicked off a boom in superhero shows that continues to this day. Where else could you possibly begin the story of the superhero TV boom? Just three years later, I have no idea where to start. The last piece ended with some thoughts on ten then-upcoming superhero shows. Just two of those ten are still airing. Seven were cancelled and one never made it to air in the first place.

The landscape of superhero television no longer has an epicentre. It’s not really a boom anymore, it’s a bubble: a big wobbly one that keeps growing and growing and growing and never bursts no matter the ludicrous shapes it takes. Last time I wrote about it, the superhero television market had at least three large competitors in Disney, Warner and Fox. But Disney ate Fox and AT&T bought out Warner so now it’s just two colossal conglomerates producing virtually all superhero TV shows. Both conglomerates have also launched their own bespoke streaming services, Disney+ and HBO Max, full of all the content they pulled from the original streaming giants who’d previously licensed it like Netflix and Amazon. Disney+ and HBO Max need to produce exclusive content on top of their deep libraries if they want to come out on top in the next phase of the streaming wars. Why not pump out a bunch of superhero shows? It doesn’t even matter that DC’s superhero shows are supposed to go on their dedicated streaming service, DC Universe: let’s release them simultaneously on both. Meanwhile, Disney is doubling down on the Marvel Cinematic Universe yet again by throwing mountains of cash at TV spin-offs for Disney+. The Falcon and the Winter Soldier. WandaVision. Loki. Naturally, the bigwigs over at Netflix and Amazon see they’re in an arms race and have ordered their own shows like The Umbrella Academy and The Boys. And on and on and on it goes.

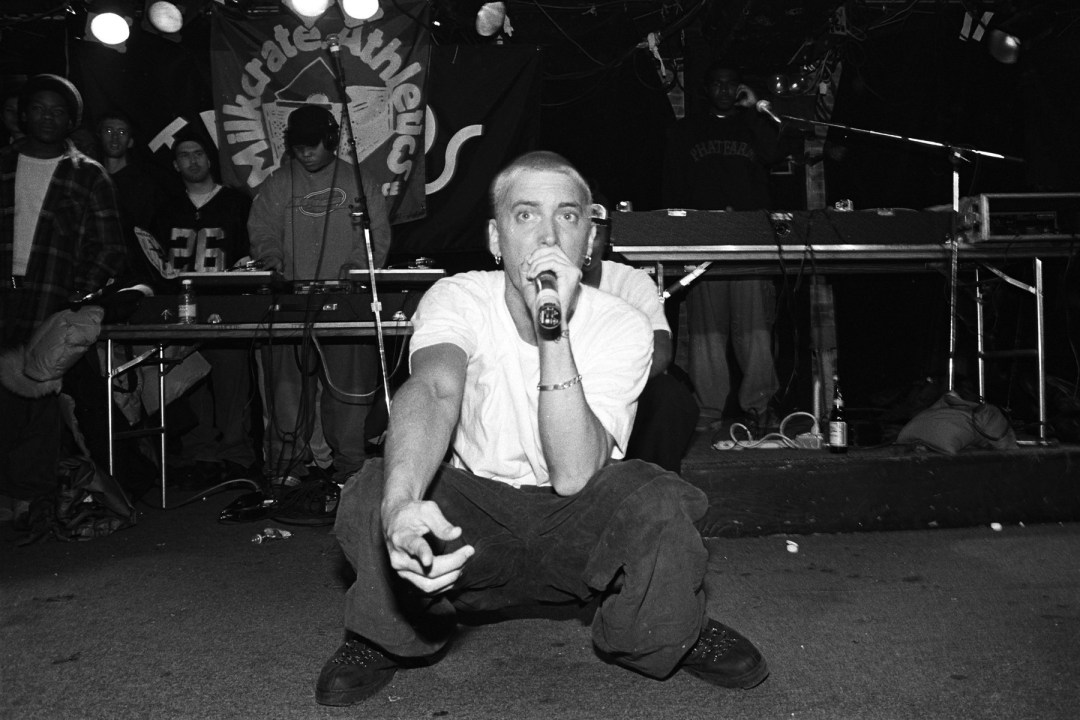

It’s hard to look at something that used to give you such joy and just feel tired. There’s nothing left of what used to excite you, just the same bland homogeneity repeated again and again into forever and beyond. I’ve loved superheroes all my life and I guess I still do deep down, but most superhero stories barely make an impression nowadays. Just an endless sea of pure content washing over me like a rock and slowly grinding me down to sand.

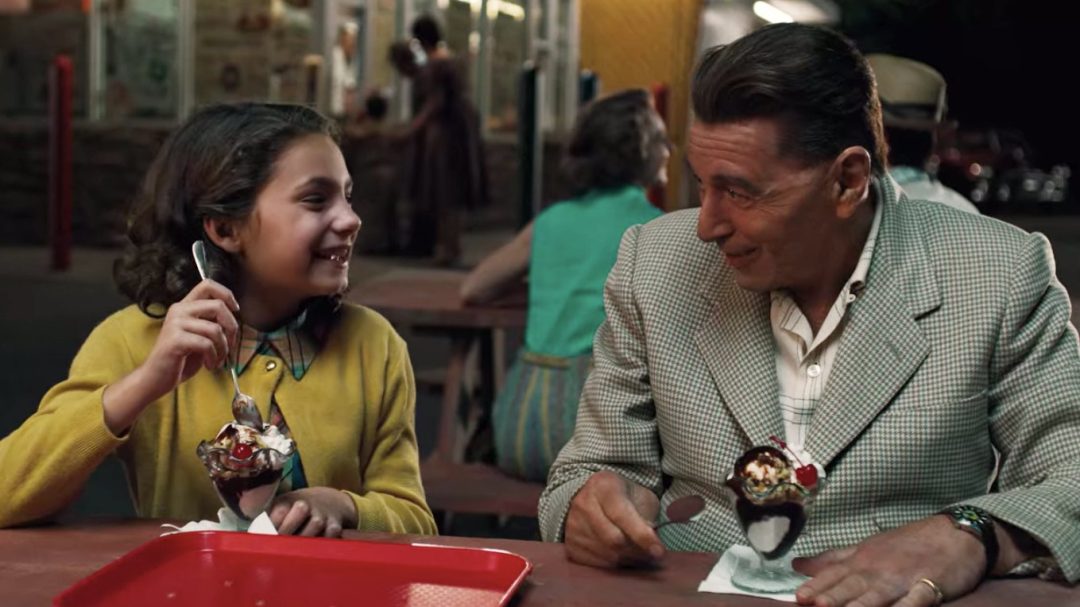

Three shows of the superhero boom that I watched to the end – Arrow, Gotham and Legion – each deserve their own retrospective. But, in lieu of anywhere else to start, I’ll still have to begin my eulogy to the genre with its last gasp.

The sixth annual Arrowverse crossover event – bringing together characters from The CW’s Arrow, The Flash, Legends of Tomorrow, Supergirl and Batwoman – was called “Crisis on Infinite Earths” and I did not enjoy it.