We’re five years into the boom in superhero television kicked off by the surprise success of The CW’s Arrow, and business is so good we’ve somehow strong-armed Noah Hawley into making a show based on a minor X-Men property. But at what cost? Arrow has just come full circle by concluding the story of Oliver’s time in exile and bringing us right back to the opening moments of the show, and the genesis of television’s superhero boom.

Now seems an appropriate time to examine and evaluate the landscape of the genre over the past five years and consider what the future may hold.

Let us begin with a tribute to the fallen: Agent Carter would still be one of the top three superhero shows on the air if only it was still on the air. It was smart and funny and understood how to balance the emotional drama we demand of good television with the pulpy fun we demand of good superhero shows. Whitney Frost should be remembered as one of the great supervillains of any superhero adaptation ever, but I suspect Agent Carter will fade tragically from our cultural memory like so many TV shows. Did you know there was a TV series based on Weird Science that ran for five whole seasons?

Powerless was one of this season’s worst debuts, a putrid mess of empty non-characters, terrible non-jokes and the bizarre, random, arbitrary use of wide-angle lenses for some close-ups but not others. The only time I laughed in twelve episodes of Powerless was the line “I used to be a caterpillar, now all I do is SCREAM”, as sung by Alan Tudyk, the most talented person in a whole cast of talented people completely misused by this terrible show. I will also concede that one of its unaired episodes, “No Consequence Day”, is sincerely good and did everything its other episodes didn’t: push forward important characters and explore the culture of a world of superheroes in a clever way. But overall, I’m glad it was cancelled, though I’m also sad because the original version of the pilot that aired at San Diego Comic-Con sounds like it was really good until it was aggressively retooled to emphasise more popular DC intellectual property, losing its creator in the process. Maybe someone else will get a chance to make a good superhero comedy without their show getting eviscerated by corporate stupidity, but that’s not what happened here and I’m relieved I’ll never watch another episode.

I did not watch any of Constantine, Powers or Sweet/Vicious, so I can’t offer them any more tribute than a half-hearted “them’s the breaks”, although the creators of Sweet/Vicious are still trying to get their show picked up at another network, so maybe them’s not the breaks after all. We’ll find out soon.

How about the shows that have survived? I’ve divided them up into five sections: DC on The CW, stand-alone DC, Marvel on Netflix, stand-alone Marvel, original properties, plus a look at the future. I’m gonna move through them in that order, rather than mangle an attempt at chronology. I won’t be covering any animated superhero series, as I haven’t watched any since Young Justice and Beware the Batman were cancelled. Besides, twelve live-action shows are more than enough to wrangle.

Let me tell you what it’s been like as a superhero fan to bombard this much schlock into my brain for five years.

Part 1: DC on The CW

Arrow

I’ve always liked TV. Once I was old enough to expand my taste outside children’s shows (though I’ve never abandoned quality kids’ cartoons), I gave hours of my life to great TV like Frasier and Scrubs, good TV like House and The Borgias, okay TV like Less Than Perfect and The Newsroom and a whole rainbow of procedurals from the Law & Order franchise to Criminal Minds to Sue Thomas: F.B.Eye. But I didn’t start to love TV until I moved away for college. I had nothing to do on my first weekend in the city, so I binged the first two seasons of Game of Thrones. I binged the first four seasons of Adventure Time a few weeks later. Then a month or so after that, I caught up on the first few episodes of a TV show I’d been hesitant to watch, but my partner assured me I’d love.

I’m still amazed by Arrow five years later. The first season is a great little show that gave the middle finger to any comic book fans expecting to be pandered to – our protagonist starts off too busy putting holes in slumlords and hedge fund managers to do battle with supervillains. Oliver Queen isn’t a superhero, he’s a murderous vigilante. We follow him in the present day as he sets out to kill everyone on a list of corrupt and wealthy businessmen left to him by his father. In flashbacks, we see how a doughy trust fund kid stranded on a desert island became a vicious outlaw with a plan to purge the city of exploitation and vice. When he gradually begins to target other criminals as villains of the week, they’re almost exclusively heavily reimagined versions of comic bad guys who are B-list at best – The Royal Flush Gang, Firefly, Count Vertigo – or based on characters who are heroes in the source material. The Blackhawks were rewritten from a heroic army squadron to a private security company staffed by corrupt Afghan War vets who robbed bank trucks on the side. Most controversially, the show reimagined the Huntress, a member of the Bat Family of superheroes, as a failed vigilante turned cold-blooded serial killer. Just two relatively famous villains appear in the first season, and both are radically different from the comics. The main antagonist of the season was traditional Green Arrow nemesis Merlyn the Dark Archer, reimagined from a nebulously defined baddie with an evil Robin Hood aesthetic for no reason to a fanatical eugenicist planning to level the city’s ghettos and kill their residents. More extreme still was the show’s interpretation of Slade Wilson, the comic villain better known as Deathstroke, who was initially portrayed as a friend, ally and mentor to Oliver in the flashback storyline, only to become his arch-enemy in the present day.

Arrow amazed me then because its casual disregard for fidelity to the source material made me feel like I had no idea what was going to happen. Smallville had an obvious endgame built into it – Clark Kent becomes Superman – and though it’s not a bad show, even as a teenager who loved superheroes, it was only ever a show I might leave on in the background if I couldn’t find anything better to watch. Now and then it would do an interesting take on a villain of the week, but there was an inevitability to the whole enterprise that made it seem like a poor investment of my time. Smallville could never surprise me, because I knew the only way it wouldn’t end exactly how I knew it would is if it got cancelled. Arrow’s flashback storyline had an endgame as it covered the five years Oliver was missing, presumed dead and how and why he returned home as a murderer, but the present-day story of his attempts to move beyond killing and be a true hero to his city felt open to all possibilities.

Arrow was committed to being a good TV show that happened to be about a vigilante with a bow and arrow, and not just a show about the Green Arrow. By the end of the first season, Oliver had two allies in his fight against crime. John Diggle was a completely original creation of the show, and Felicity Smoak was essentially one too, even if she shared a name and a similar profession with an otherwise unrelated and forgotten character from the 1984 Fury of Firestorm comic series. Both were given prominence in the show at first equal to and later exceeding any of the characters derived directly from Green Arrow comics, and most of those characters already shared little with the source but their names, with the sole exception of a substance abuse storyline for Oliver’s sister Thea (a reimagining of Mia Dearden, the second incarnation of Green Arrow’s sidekick, Speedy) that was loosely borrowed from the iconic Green Arrow/Green Lantern anti-drugs comic “Snowbirds Don’t Fly”, in which the first Speedy develops a heroin addiction.

As the show moved into its second season, no character felt safe just because they might eventually become the superhero who has their name in the comics – the show had already killed off a member of the regular cast (Oliver’s best friend, Tommy Merlyn) in season one and went on to kill another (Oliver’s mother, Moira) in season two. By the third season, even Oliver didn’t feel safe, and his seeming death in the mid-season finale was taken seriously as a possibly permanent plot development in the weeks before the next episode aired. In the fourth season, the writers killed off Laurel Lance (aka Black Canary), who’d been one of the show’s leads since the very start, and though I criticised that decision at the time, and still do, it’s a testament to the unsentimental and ruthless approach to craft that has made Arrow so reliably entertaining for five seasons. Even if the weakly-plotted third season and tonally-muddled fourth didn’t hang together as a whole, both are full of great individual episodes like “Suicidal Tendencies” and “Beyond Redemption”, and season five’s “Underneath” is both a masterpiece of episodic plotting and one of my all-time favourite bottle episodes. One of the show’s best qualities has always been that even when the big picture is blurry, its craft shines on a week-to-week basis. Arrow still amazes me five years later at least in part because it’s never lost that commitment to being a good show on its own terms – well-choreographed stunts and well-directed action, nuanced characters with strong relationships and punchy well-paced plots – instead of pandering to comic book readers. The most recent season ended with a cliffhanger explosion that may have killed any of over a dozen major characters, and I haven’t written off any of their deaths as possibilities.

But Arrow wasn’t always the most rewarding show to watch. The last stretch of the third season fell flat on its face due to a weak villain, poorly-defined stakes and a finale full of goofy, contrived plot devices, while the fourth season backed itself into at least three absurd creative decisions (Felicity’s sci-fi recovery from paraplegia, Oliver and Felicity’s breakup, and the redirected nuke) out of a misguided desire to escalate a show that’s at its best with its feet firmly on the ground. The show spent a good chunk of its second season building up creative good will and narrative justification to introduce a limited form of super strength to its universe for just that season because of its commitment to street-level superheroics, then suddenly found itself in a shared continuity with The Flash from season three onwards and Legends of Tomorrow from season four. Shying away from the implications of that shared continuity was never an option, especially with an annual crossover event, but I suspect many viewers would agree that Arrow bungled most of its attempts to engage with this sudden influx of sci-fi and fantasy elements.

Moreover, the death or departure of many of the show’s older characters (both in age and longevity in the cast) over the course of the first three seasons gradually created a rift between Arrow and its sense of its own history in the third and fourth seasons, especially after the death of Oliver’s mother in season two, Roy’s departure in season three and the utter emptiness of the fourth season’s flashback storyline, in which nothing significant happened to Oliver except what was necessary for the plot to send him to Russia for the fifth season flashback. The show began with Oliver trying to atone for his father’s crimes by murdering millionaires, and the second season’s plot was driven by the conflict between Oliver and his flashback-friend-turned-enemy Slade, but the show lost track of these core themes of legacy and sin and moral reckoning in the third season’s war with ninjas, and forgot them altogether in the near-apocalyptic nonsense of the fourth season. When season four ended with Team Arrow scattered to the wind, its members worn down by loss or haunted by guilt or just dead, I worried that Arrow had reached a point of no return, and season five would be its funeral.

Instead, season five was a rebirth.

I went into season three with no fear the show would disappoint me because I’d enjoyed the first two seasons so much – season two remains one of my favourite seasons of television ever – and any time I felt unsure about how the season was unfolding, I put my uncertainty to one side because I was sure it would all come together in the final stretch. But the final stretch was where it imploded. When I started the fourth season, I went in with my hackles raised a little, but the show did some interesting things at the top of the season that made me think it was gonna walk back some of its bad decisions from the previous season, and it did…until it made new ones that were even worse. So when season five started off great, I held back. I didn’t permit myself to enjoy it too much, even with an episode as excellent on its own terms as “Human Target”. I didn’t want to get stung again, and so it wasn’t until late in the season that I finally let myself say it: this show that I loved had finally remembered what it was supposed to be.

Everything good the show had lost in the previous two seasons was brought back to the fore. The themes of legacy and sin, and the show’s sense of its own history, were a central part of the plot, as Oliver faced off against Prometheus, a villain intent on punishing him for his time as a murderer. The old generation gap between Oliver, Thea, Laurel and their parents was recreated with Oliver’s new team of younger vigilantes, who grappled with the events of previous seasons from a completely different perspective to the allies who’d followed Oliver on his journey from serial killer to superhero and knew the grey between, while the newer heroes were suddenly confronted with the fact that their leader used to kill people every week. The flashback storyline brought events full circle with Oliver’s time as a member of the Bratva, and the final events that led him to embrace his darkness and return home as a murderer. Arrow has never shied away from discussions of the morality of vigilantism, and it’s always been smarter about those debates than most superhero shows or movies in part because it consistently refused to give firm answers or pick sides, and never trapped its characters in a smooth inevitable growth towards moral decency – season four ended with Oliver abandoning the no-kill rule he adopted in season two to put down Damien Darhk for good. The show acknowledged Laurel’s role as the ethical heart of the team by letting its characters become corrupted in the wake of her death, and their attempts to find an imperfect but liveable relationship with the moral grey area in which they operate is a major theme of season five.

Even so, I never expected an episode of Arrow like “Kapiushon”. Captured by Prometheus, Oliver is tortured into admitting his most terrible secret, a secret we learn is true beyond doubt as we watch him engage in clinical cold-blooded torture of his own in the Russia flashbacks. “Confess, Oliver. You don’t kill because you have to, so why?” Prometheus asks. “Why do you do it?”

“Because I wanted to,” he answers almost too quick to hear.

“What?”

“I wanted to,” he whispers breathlessly. Then he screams. “I wanted to! And I liked it!”

Our hero, a man whose halting but earnest steps towards the light we’ve watched and cheered on for five years reveals that we never truly understood the depths of his darkness, and given chance after chance in subsequent episodes to claim it was just something he said to make the torture stop, he refuses: he wanted to kill people. He liked to kill people. I’m still blown away by the guts of that move. Lots of mainstream superhero narratives toy around with the idea their heroes might enjoy violence – Captain America questioning whether he could ever be anything but a soldier in Avengers: Age of Ultron springs to mind – but for Arrow to lean the whole way into it and have the protagonist admit that he’s a serial killer, and not just in the technical sense, but in the deepest and most profound sense of himself as a person, was one of the more risky, ambitious and thrilling events on television this year. I realised immediately that I’d been too cautious in my hope for the show, and allowed myself to really enjoy the last third of the season.

The next three episodes rewarded my newfound optimism in the show’s future. “Disbanded” pitted Oliver against his own team as he ordered the team to disband and then traded control of the city’s underworld to the Bratva in exchange for the assassination of Prometheus. Just a week after Oliver was talked out of a slide into the dark, “Dangerous Liaisons” finally allowed Felicity to explore her moral ambiguity in a way the show had denied her for four and a half seasons by pitting her against the rest of the team as she helped a hacker group free their imprisoned leader. In the aftermath of both conflicts, “Unleashed” trapped Oliver and Felicity in a small environment (the Arrowcave, as it filled with methane) and managed to rehabilitate the paraplegia storyline by using it as a clever device in its brilliantly-plotted present-day storyline and brought their relationship back into focus with a tender and affecting flashback about an undisclosed fling during the inter-season time jump. With the debacle of the redirected nuke handled as well as such a ridiculous plot device could be earlier in the season, and the on-going effects of Laurel’s death echoing both overtly and implicitly throughout the season, season five did the impossible and somehow managed to tell a great story – several great stories, really – while reckoning with its recent missteps, giving all its characters a meaningful arc and bringing the story thematically full circle in a way that didn’t just close this chapter but opened the next.

Even the one episode that didn’t work that well – “Spectre of the Gun” – I could still respect for the ambition of its sincere but silly attempt at a political issues episode. I also had some problems with this year’s crossover episode, “Invasion!”, because it meant the show had to endure the indignity of its 100th episode taking place in a goddamn spaceship, but the story it told was so emotionally rich and self-contained that I could forgive it, even if I can’t forgive the shared universe itself for, again, and I can’t stress this enough, setting the 100th episode of Arrow, a show about a team of vigilantes who mostly fight street-level criminals, on an alien spaceship.

If even that episode couldn’t disappoint me, I can’t wait for season six.

Arrow was the third show in my journey from someone who liked TV to someone who loved TV. At the same time that it kicked off the boom in superhero TV shows, it also helped to turn me into the person I am today, a hermit who watches seventyish on-going TV shows and writes about only a few of them on this blog. Arrow was the first show where I actively shipped a couple and the show that completely disillusioned me with shipping. I learned to love stunt choreography and action directing from Arrow, and it was the show that taught me to appreciate the craft of scrappy little genre shows that don’t have the budget for prestige production values, but still have talent and heart behind them. Without Arrow, I’m sure I’d be a massive TV snob, and would never have appreciated the high-fructose pleasures of trashy network shows like Grimm and Once Upon a Time, or the audacity and brilliance of low-budget sci-fi shows like 12 Monkeys and Dark Matter. I’d have none of the good will and patience that helped me find diamonds in the rough like Between or Cleverman. I would sincerely not be who I am today without Arrow, and I’ll always love it for that if for nothing else.

But, for most people, if Arrow matters at all, it matters because every superhero TV show since owes its existence in no small part to the success of Arrow. Arrow was the TV equivalent of a crossover hit, finding an audience outside the traditional market that normally lets scrappy little genre shows just about survive, but never make a meaningful cultural splash. Now, we have twelve superhero shows on the air and more on the way, including at least one show that’s a serious Emmy contender. From zero to twelve in five years with only a handful of flops on the way is an astonishing boom.

Unfortunately, the boom itself might be Arrow’s most unforgiveable failure.

The Flash

I can’t really explain the sheer wonderful joy of watching The Flash as it aired its first season, and I know because I tried at the time and I didn’t come close. Between season two of Arrow and the premiere of The Flash, I watched Greg Berlanti’s first superhero show, No Ordinary Family, and I was already excited for another show as light-hearted and fun and sincere in its enthusiasm for the genre. We still complain today about how grim and foreboding the superhero genre is, but now Paul Rudd is a wise-cracking shrinking guy, Deadpool is one of the highest-grossing superhero films ever, and we have Supergirl and Legends of Tomorrow to light up our TVs. The Flash premiered a month or so after Guardians of the Galaxy and it’s hard to remember now just how much of a breath of fresh air they were, how fun and bright and warm, so I’d like to jog your memory by listing and briefly describing the plot of every mainstream superhero film made between The Avengers and Guardians of the Galaxy:

- The Amazing Spider-Man: Andrew Garfield faces his greatest enemy yet, Columbia Pictures, as they turn his dream of playing Spider-Man to shit by putting him in a Spider-Man movie where the plot is driven by corporate intrigue instead of silly people in costumes.

- The Dark Knight Rises: Bane and his army of terrorists break Batman’s spine and lock him up in a prison, then use the threat of a nuclear attack to enslave Gotham City, and mass execute and immiserate its residents.

- Iron Man 3: Isolated and alone when a terrorist attack on his home leaves him stranded in rural Tennessee, Tony Stark must figure out a way to rebuild his suit so he can prevent an evil businessman from assassinating the President and installing a puppet to replace him, also Tony is struggling with PTSD.

- Man of Steel: A horrible waking nightmare in which the adopted alien son of farmers from Kansas is raised to feel no empathy for other people, and then murders thousands of people. We’re supposed to think he’s a hero.

- The Wolverine: Logan must protect the granddaughter of an old friend from the Yakuza, who her father has hired to kidnap her so he can personally murder her, also Logan is struggling with PTSD.

- Thor: The Dark World: An evil space elf lays waste to Asgard and murders Thor’s mother, so he teams up with Loki to bring the space elves down, also Loki is struggling with PTSD

- Captain America: The Winter Soldier: Captain America is framed for the murder of Nick Fury and goes on the run with Black Widow to expose a vast conspiracy by Science Nazis to seize control of SHIELD and use its resources to take over the world by genociding millions of people with drones.

- The Amazing Spider-Man 2: Andrew Garfield faces his greatest enemy yet, Columbia Pictures, as they force-feed him the pile of shit that was once his dream of playing Spider-Man by putting him in a Spider-Man movie where he attempts to unravel the conspiracy of his parents’ murder and fights a sad confused autistic man who was experimented on by a mad scientist and his childhood friend who went crazy after injecting an incomplete cure for his terminal illness because Peter refused to help him make a better one for no reason, also Peter struggles with snapping his girlfriend’s spine in half.

- X-Men: Days of Future Past: Wolverine travels back in time from an apocalyptic future in which we watch all the X-Men we know and love die to change the past with the help of a young Charles Xavier, who is struggling with PTSD, also drug addiction.

I like a lot of these movies (four, to be precise) and I love Arrow, but the singular domination of the genre by such a dark tone was suffocating and it seemed like it might never end. Never again would Clark Kent change into Superman by running through a revolving door. He was too busy snapping necks and screaming in anguish. Then, suddenly, there was hope. Guardians of the Galaxy was a ray of light, but The Flash promised an hour of sun every week for half of the year, and I’ve never been more excited about a television show in my life.

The Flash was everything I hoped it would be and more. I’d never seen a show that wore its heart on its sleeve with such pride and conviction, and I fell in love with its characters over and over again as they faced the world with hope and courage and kindness. The Flash made superheroes fun again, with goofy one-liners and hammy performances and a full-throated embrace of the genre’s inherent silliness, yet it never sacrificed the heart and emotion that make the best superhero stories more than just a lark. The Flash had clever plots with clear stakes and a well-developed world that felt lived-in thanks to its cast of recurring civilian characters like Cecile Horton, Tina McGee and Linda Park and background details like the casual progression of Captain Singh’s relationship with his boyfriend/fiancé/husband. More than anything, The Flash felt excited to be here, grateful for the opportunity and eager to show us all what it could do, which turned out to be way more than I anticipated.

By something between coincidence and mutual reinforcement, I grew into my deep love for popular culture over the same time period when, among other things, I reconnected with the Catholic faith I’d rejected as a teenager, and the first season of The Flash was one of the first television shows where I found artistic expressions of the feelings of wonder and awe that I’d begun to relearn. In the finale, when Eddie Thawne, the purest of humanity’s children, shoots himself in the heart to prevent his evil time-traveling descendant, the Reverse-Flash, from killing Barry and everyone he loves, I was overcome with a sense of terrible beauty. I didn’t understand it at the time because it far exceeded even the fact that Eddie was my favourite character, but I now recognise it stemmed from the fact that Eddie underwent a small crucifixion, sacrificing himself to destroy an agent of death. I was still early in my journey back to Christianity at that point, and so I didn’t link the two, but it was illustrative to figure it out later. It helped me see how even art without a particularly religious or anti-religious point of view can articulate religious feelings and concepts in truly affecting and interesting ways, from 12 Monkeys’ portrayal of miracles to the dark nuanced exploration of grace in The Booth at the End to the crisis of mankind’s fallenness in Review. To this day, I can’t watch Eddie’s death scene without crying.

Unfortunately, there were further seasons of The Flash.

The Flash went to shit in its second season, and somehow got worse in its third, so bad that I stopped watching it after the midseason finale. I can’t overstate this enough: a show whose first season I literally just compared to a religious experience became so terrible that I couldn’t stand to watch it anymore. I’m anxious about whether YA sci-fi schlock Between will get a third season, I still hold a grudge about the cancellation of The Following, a show I’m not embarrassed to describe as maybe the dumbest television show in history, and I’ve watched all six seasons of Grimm and Once Upon a Time but The Flash just sucks.

I’ve written previously about the second season and I don’t want to go over all my criticisms of its complete abandonment of logic again, but here’s a sample from an old, now-unlisted blog post:

“After the team put Barry in the pipeline [a superhuman prison] while they go deal with Zoom [the main villain of season two] themselves, Jesse stops to tell Harry [her father] that she’s going to go back to Earth-2 [the parallel dimension they’re from] after they’ve defeated Zoom, but she doesn’t mind if he wants to stay at STAR Labs [Team Flash HQ] with his new friends.

But they later reveal that their whole plan is to throw Zoom through a breach back to Earth-2 and seal the breaches forever. Never mind that they already did that and then changed their mind because it wasn’t fair to sacrifice Earth-2 to protect Earth-1. Here’s a problem of pure story logic: when and how was Jesse planning to get back to Earth-2? And why would Harry not immediately respond to her plans by screaming “BUT WE’RE SENDING ZOOM BACK TO EARTH-2 AND HE’LL KILL YOU” in her face?”

I have so many criticisms to make of The Flash that I keep them in a note on my phone called “Bed Thoughts – 24/11/16”, a note that I’ve updated at least once a month since last November, even though I’d stopped watching the show and didn’t have any new problems to add to it, just old ones to notice in retrospect. The Flash went to shit so fast and so brutally that I thought of new stuff to criticise in the twelve hours between when I started this section of the article and reached the end of this sentence. I can’t fit them all in this article, and I don’t want to either. I’ve had a nicer time of life since I stopped watching The Flash and I don’t want to piss myself off by going on a deep dive into a show I’d rather put out of mind forever.

Instead, let’s switch genres.

#5: Flashpoint

At the time of the second season finale, I made three predictions about The Flash’s decision to adapt the 2011 comic “Flashpoint”, in which Barry wakes up in an alternate timeline where his mother was never murdered. My first prediction was that the dramatic stakes of the adaptation wouldn’t make any sense, because in the comic Barry doesn’t know he’s the one who changed the timeline, but he does on the show. I was right. Even though both versions involve Barry forgetting his original life, on the show, when he decides he doesn’t like the timeline he’s created after all, he just changes time again because he already knows he created the new timeline, whereas that’s a major twist in the comic, where he assumes it was the Reverse-Flash and spends the whole story trying to find him. My second and third predictions were about whether the Flashpoint timeline would be shown on Arrow and Legends of Tomorrow to avoid spoiling whether Barry undoes it:

“…The Flash is a show that shares a universe with other TV shows that will either be affected by this narrative choice, which would be disorienting and alienating for Arrow viewers who don’t watch The Flash in particular, or will not be affected, either because they take place back in the original timeline after the storyline is resolved, in which case viewers of both shows will know its impact straight away, or because Arrow will just not refer to it in any way…”

The show didn’t show the Flashpoint timeline on Arrow or Legends of Tomorrow, and I have to own up to a bit of stupidity on my own part. I never considered that The Flash would be so stupid as to have time travel in The Flash permanently alter the shared reality of all three shows even though not everyone who watches one show watches them all. However, they did just that by reversing a plot point from the original comic, where “time echoes” or whatever caused random changes to the new timeline causally unrelated to Barry saving his mother, e.g. Bruce Wayne is killed in the alley, and his dad becomes Batman, while his mother is the Joker. In the show, it’s the original timeline that experiences random changes from “time echoes” or whatever that were causally unrelated to Barry changing it back. Cisco’s brother is killed in a car crash, Iris isn’t speaking to Joe because of a falling-out and Caitlin has secretly developed the ice powers of her evil Earth-2 counterpart, Killer Frost. Barry is arbitrarily stopped from fixing them by the Flash of Earth-3, who tells him that if he messes around with time any further, he’ll attract the attention of the monsters that kill people who mess around with time too much. Much of the season becomes about Barry facing the repercussions of these changes.

I’ll deal with the other problems that came out of that creative decision later on, but its effects on the shared reality were so stupid I’m still processing them. I don’t mind too much that Martin from Legends of Tomorrow was given an adult daughter he can’t remember, because at least Legends of Tomorrow is itself a time-travel show and it wasn’t totally irrelevant to the plot. But for The Flash to change Diggle’s daughter Sara into Diggle’s son John Jr. on Arrow was bonkers – it was an impact with no impact, a symbol to represent consequences that had no consequences. No one on Arrow had their life affected by “Flashpoint”, but it still had to make a bizarre change to the show just to let the viewer know that “Flashpoint” happened, I guess. I hate every way these shows are forced to crossover for no good reason, but this was the worst, a dumb empty show of force signifying nothing.

#4: Misogyny

The Flash treats its female characters like crap, and it’s just embarrassing. The way the life and body of Barry’s mother Nora act as a prop for his personal development is genuinely disgusting and I was really uncomfortable with it by the time Barry teamed up with the Reverse-Flash to go back in time and send the Reverse-Flash into his childhood home to murder her. Nora is the first but not the last female character expected to exist just to further Barry’s emotional development. His only love interests beside Iris are both hastily written out of the show for unclear reasons once they’ve fulfilled their usefulness to Barry’s character arc, even though one of them is a co-worker and friend of Iris’s and should presumably reappear. Though, to be fair, the show just stopped portraying Iris at work in season three, because that’d be a distraction from her relationship with Barry, which is the only way she matters to the show at all. Caitlin doesn’t get a storyline that’s not about her relationship with a man until season three, and that storyline is about her being turned evil by ice powers that Barry gave her by screwing up the timeline.

Of course, it’s not clear why the ice powers would turn Caitlin evil, but she’s not the first woman who just can’t control her powers for no reason, which is a very weird thing to happen exclusively to female characters – Plastique, Trajectory, Magenta – but I guess women are just so bad at controlling their emotions that every season of The Flash must have a woman with superpowers she can’t control and we must live in a world where it is a pleasant change of pace that at least none the women with superpowers in season three explode. In fact, all the female villains are pretty pathetic in one way or another. Peek-a-boo and Doctor Light are scared and incompetent, Trajectory goes crazy from her powers and vaporises herself, and the Top is an idiot who gets decked with one punch even though she’s a professional criminal. The only exceptions are Bug-Eyed Bandit, who only appeared once and then moved to Arrow, Black Siren, who only appeared once and then moved to Arrow, and Golden Glider, who never appeared without her brother, Captain Cold, and so stopped appearing once he moved from The Flash to Legends of Tomorrow. Jesse Quick is the only female speedster who didn’t vaporise herself, so of course she’s the slowest. No one in the whole show has a mother who’s both nice and alive, but the world is full of loving fathers, from Joe West to Henry Allen to Harry Wells, only one of whom dies.

And, of course, there’s Iris, who always existed just to marry Barry, but exists more and more just to marry Barry with every passing season. Unable to contribute to the team due to her lack of practical skills, you’d think the show would find a way to use her job as a full-time investigative reporter in some way, but no, her real job is to sit there and love Barry and be loved by Barry and not much else.

#3: Secrets

Here’s the plot of every episode of The Flash:

Someone has a secret they’re keeping from the rest of the team for no reason!

Oh no, the secret is exposed! Everyone is so hurt by the deception!

Someone gives a speech about how “come on you guys, the team can’t work if everyone isn’t honest with each other and we’re a family!”

Everyone shakes their heads solemnly, and then they all go in for a group hug.

(five minutes later)

Someone has a secret they’re keeping from the rest of the team for no reason! Tune in next week to find out what happens!

#2: Incest

I’m a little nervous to write about this because hardcore shippers have spent hours tweeting at me that I’m a paedophile and a racist for saying this before, but I’ll say it anyway: there are creepy incestuous undertones to Barry and Iris’s relationship and the show refuses to just admit it and deal with it and it makes it really hard to watch when they’re the official couple. Barry was raised by Iris’s father from the age of eleven and Barry consistently refers to Joe as his father. Barry is Joe’s son and Iris is Joe’s daughter, but I’m supposed to believe they don’t have a sibling relationship? Patty refers to Barry as Iris’s brother in her presence and Iris doesn’t correct her or seem disturbed by her choice of words. Now, sure, they’re foster siblings or adopted siblings or whatever, but it’s not the blood relationship that makes incest gross, it’s the perversion of the family bond, and even if I were to accept Barry never saw Iris as his sister, I don’t believe Iris never saw Barry as her brother. I don’t even buy that she ever stopped seeing him that way, and it’s gross, and even if it wasn’t, they have no chemistry, so it’s weird how the writers could be so passionate about the relationship, but also not passionate enough to make even the smallest effort to overcome an incest subtext.

#1: Everybody Loves Barry

I stopped watching The Flash because of the seventh episode of the third season, “Killer Frost”. I watched the last two episodes before the winter break, the eighth because it was part of the annual crossover and the ninth to give the show one last chance. But it was “Killer Frost” that really put the nail in the coffin, and specifically this line:

“Man, I knew you were a hero, but this!?”

Joe says this to Barry when Barry resigns his job to buy off someone who saw Caitlin commit crimes while turned evil. Caitlin is only turned evil due to Barry’s actions and the show has made a point of showing that Barry isn’t particularly good at or interested in his job – he only became a CSI because he wanted to solve his mother’s murder, he was always late with reports until he developed super speed, and he constantly blows off work to be a superhero now. Barry is also independently wealthy because his nemesis left him a scientific research company in his will, so he’s not putting himself on the street, and he’s not doing anything to help Caitlin get better. He does the bare minimum he can possibly do to not ruin Caitlin’s life even more, at no real cost to himself.

To which Joe responds:

“Man, I knew you were a hero, but this!?”

The Flash gave me so much to hate as it moved from the near-perfection of the first season to the utter piss of the second and third, but the worst thing it did was insist on pursuing a darker tone and refuse to accept the consequences. The Flash wanted to worship Barry’s heroism like it did in season one, but it also wanted Barry to have killed his best friend’s brother and ruined his other friend’s life by giving her superpowers that turned her evil. I read somewhere that season three ended with Barry sacrificing himself to the Speed Force to atone for his mistakes or something, but even if I pretend his sacrifice is gonna stick and ignore the overwhelming likelihood he’ll be back within the first three episodes of the next season, it feels like too little, too late, and not what I wanted. The Flash was supposed to be the show that took away the pain and reminded everyone what it felt like to watch a superhero on a screen and feel happiness instead of the loud pounding drone of our souls flickering apart out of sheer boredom.

The Flash was sweet and heartfelt and fun, and now it’s just a dour puddle of crap. I don’t even have the energy to complain about the writers using increasingly faster and more evil speedsters as the main villain for every season. I’m done.

Legends of Tomorrow

Legends of Tomorrow burst onto our screens in the worst way possible: through the ribcages of Arrow and The Flash. If you were a crossover sceptic like me, there was something horribly parasitic about watching the two-hour Arrow/Flash crossover/backdoor pilot for Legends of Tomorrow in 2015. Previous crossover events had mostly been clever and restrained: the two episodes that we now know as the first annual crossover event, “Flash vs. Arrow” and “The Brave and the Bold”, were self-contained episodes of each show where the two casts took turns helping each other with a case of the week. The Flash’s “All Star Team-Up” and “Who Is Harrison Wells?” were self-contained episodes that just happened to have exactly two Arrow cast members each as guest stars. The only hint we’d had so far of what was to come was Oliver’s guest appearance in the penultimate episode of The Flash’s first season, when he was deep undercover with ninja terrorists on Arrow, and Barry’s guest appearance in the finale of Arrow’s third season, when he had time to run to the Middle East to free Team Arrow from the bad guy’s prison, but no time to help them beat him, even though he’d just captured the Reverse-Flash with Oliver’s help in the previous episode.

Those were silly, but only if you were watching both – the problem was the continuity between the shows, not within each show. But the Arrow/Flash crossover/backdoor pilot for Legends was disruptive to the two host shows, even before the episodes themselves. If you’ve never heard of the time-travelling superhero team called the Legends of Tomorrow, that’s because there’s no superhero team called the Legends of Tomorrow – they were made up for the TV show, and that’s neat on one level, as a return to the “fuck you, who gives a shit about comics” attitude of early Arrow. Unfortunately, it’s in service to a different kind of pandering.

The team is composed of recurring characters from the other shows, and that meant Arrow and The Flash had to spend some of the earliest episodes of their seasons on getting all the characters in place to spin-off. Arrow had to bring Sara Lance back to life to become the White Canary and solve the mystery of Ray Palmer’s disappearance so he could be the Atom. Sara’s resurrection was handled well with a multi-episode arc that bordered on a horror story at times, while Ray’s return was meh, but it hardly matters anyway, because both storylines were just there to be written off the show, and it threw the whole balance of the opening episodes way off. The Flash had a similar problem with setting up some backstory for Captain Cold so his turn from villain to anti-hero would be more plausible, rebooting Firestorm after one of the two people who merge to form him died in the season premiere, and introducing Hawkgirl as a love interest for Cisco so she doesn’t just show up out of nowhere for the crossover, I guess.

By the time the crossover aired, I was nervous, and rightly so – it’s entertaining enough if you watch it as a TV movie, but in the context of each series, it’s a mess, even if you already watch both shows and don’t suddenly find yourself forced to muddle through on a vague idea of who the other show’s characters are. Oliver finds out his ex-girlfriend Samantha didn’t terminate her pregnancy, but gave birth to and raised their child, in an episode of The Flash and even with a “previously on…” segment, it’s just crazy that such a big moment for Arrow’s lead happened on The Flash. Most bafflingly, the crossover ends with Merlyn, at that point an uneasy ally of convenience with the heroes, helping the crossover’s villain come back to life so he could continue to serve as the main villain for Legends of Tomorrow, for reasons that remain unexplained.

But that’s the crossover pilot. What about the show?

It’s fine.

I wish I could praise it more. I wanted to like it, and I don’t dislike it, but I can’t imagine committing to watching it every week. The writers aren’t as good at handling the ensemble as the ensembles of the other shows, and they’re so bad at writing characters introduced for the show that Hawkgirl and Hawkman get written out of the show at the end of the first season, even though the whole season was about their conflict with the immortal villain. The founder of the team was written out at the end of the second season in a blatant Poochie exit (“I have to go now, my planet needs me”), and the second season reused four villains from Arrow and The Flash for their version of the Legion of Doom, because why not. The only new characters they haven’t written out yet are dull as dishwater. And I know it’s not fair, but this seems like an inopportune moment in history to announce the next hero from the comics you’re introducing is Isis, so I’m not sure why they didn’t just focus the next season on deepening the ensemble a bit instead of expanding its roster.

Episode-to-episode, Legends of Tomorrow is decent action schlock that doesn’t go hard enough with its silliness to compensate for the lack of a good overarching story with the simple kinetic delight of lots of people hitting each other. You’ve seen every episode before in dozens of TV shows and hundreds of movies, whether it’s an undercover mission to infiltrate the Nazis or a showdown at high noon with a generic black hat, but in lieu of surprising you with a plot that’s not completely rote and formulaic, Legends of Tomorrow offers you nothing. Some of the character development is interesting – I never expected Heat Wave, of all people, to become its deepest and most tragic character – but it’s too broad most of the time when a lot of strong specific character work is the only thing left to make your show worthwhile if you don’t want to do a lot of plot or a lot of action. I’m also not entirely convinced the writers have a firm grasp on the tone. The second season includes an episode set in the US Civil War that involves the black members of the team being taken as slaves and tortured and ultimately leading a slave revolt, which is genuinely moving in isolation, but it’s sandwiched between a wacky samurai episode and a wacky Cold War episode where Heat Wave tries to teach the Atom how to be a badass by robbing the White House, and the contrast does not hold up well.

I didn’t finish either season of Legends of Tomorrow, so maybe I’ve missed all the great episodes and I’ve just made a complete ass of myself by talking shit about a show I didn’t finish, but I doubt it. I’ve known great shows that were missed by critics who didn’t finish the first season – BoJack Horseman in the most infamous case – and I just don’t believe Legends of Tomorrow is one of them. If I walk into a room and Legends of Tomorrow is already on TV, I wouldn’t mind sitting down for one episode, but that’s the highest praise I can give it, and that’s not enough.

Supergirl

Supergirl is a messy show with a good heart and I worry for its future. When it debuted on CBS two years ago, I couldn’t know The Flash’s descent into darkness and the general meh-ness of Legends of Tomorrow would leave it to stand alone as the only bright optimistic superhero show on TV. Supergirl felt like a welcome addition to a revival of the genre’s heart, but now it’s the last hope for happiness, and all I can see are red flags that make me fear it’s about to succumb to all the problems that drove The Flash into the ground, and new problems of its own.

If I have any faith left in it, that faith is called Melissa Benoist.

Her portrayal of Kara Danvers is one of the best performances on TV, and I credit it entirely to her, because the material she’s given is so often the worst kind of schmaltz and shallow sentimentality, but she sells it flawlessly almost every time. Her commitment to the character makes Kara feel alive in a show where every other character teeters on the brink of cliché. She uses the tiniest expressions and smallest gestures to express the soul of her character, and delivers every line of dialogue with such complete sincerity that you never doubt it’s exactly what Kara would say in that moment, even when it’s the corniest shit in the world.

I knew Supergirl had the potential to be great very early in its first season when it aired “Human for a Day”, one of the year’s best episodes of television. After using a supercharged version of her heat vision in the previous episode, Kara loses her powers, only for an earthquake to hit National City and spark looting and riots. Kara tries to help in the chaos despite a broken arm, and ends up at the side of a dying man with on-again-off-again villain Max Lord. Neither of them are able to save him, which leads to the following pair of scenes:

The nuances of Melissa Benoist’s performance shine in comparison to her co-stars, even the hardly untalented Callista Flockhart. The episode’s B-plot also resulted in a massive subversion when Kara’s sister Alex and her boss Hank Henshaw have to stop an escaped alien prisoner at the Department of Extranormal Operations (DEO). Hank Henshaw is best known in the comics as the Cyborg Superman, a supervillain who originated in the 90s Death of Superman storyline and floated from story to story thereafter, including a stint as an enemy of the Green Lantern, and the show had already teased the reveal with incredibly unsubtle shots of Hank’s eyes turning red. But in a twist that made me jump around and pump my fist in the air, he reveals himself as the Martian Manhunter, my favourite DC superhero and the most underserved character in the publisher’s history. The rest of the season didn’t always live up to the potential it showed in “Human for a Day”, though “Falling” came close when it continued its exploration of Kara’s anger by turning her evil through exposure to Red Kryptonite. I had high hopes for the second season, a nice counterbalance to the despair I felt over The Flash and Arrow.

Then came the big announcement: Supergirl’s ratings on CBS couldn’t justify its budget, so it was to be moved to The CW with a reduced special effects budget and a switch of shooting location from Los Angeles to Vancouver to cut costs. Callista Flockhart departed from her role as the show’s breakout character, Kara’s boss and mentor Cat Grant, to stay close to her family in LA. The show was about to be retooled, but I stayed optimistic because I already knew what Berlanti Productions could do on a CW budget and it was easier to believe the show would survive the change to a thriftier production than admit the fight for the genre’s soul was over.

The results were mixed.

The integration of Kara’s tech whiz friend Wynn into the DEO side of the story with Alex and J’onn was smart, as was the promotion of James Olsen to CEO of the news company where Kara works in the wake of Cat Grant’s abrupt departure, and Kara’s promotion from assistant to reporter under the new editorship of the old-fashioned cantankerous newsman Snapper Carr. I thought the decision to use season two to explore Kara’s struggle to be both Kara Danvers and Supergirl was a well-conceived natural follow-up to the first season’s exploration of Kara learning to be a superhero after years in hiding, and scaling up James’s role in her civilian life to balance out the transfer of Wynn into her superhero life was an effective way to avoid isolating James from the story too much. Alex’s coming-out storyline and relationship with her first girlfriend, Maggie, was pleasantly well-executed and managed to avoid the trope of the perfect gay couple who never have conflict or relationship problems, though it’s silly that they were engaged by the end of the season. The top half of the season used alien refugees to explore issues of immigration and asylum in a way that felt both timely and timeless, unbeholden to the constraints of the current political moment, but effortlessly relevant to it.

Other ideas weren’t so great, and the worst of all was the almost total abandonment of the newsroom as a setting when James decided he wanted to be a vigilante all of a sudden and talked Wynn into making him a supersuit so he could become the Guardian, a C-list superhero that shares the name of a real-life newspaper, though no one made the obvious jokes. Kara’s journalism career was sidelined in place of a new romance with a fairly bland new character, Mon-El, a decision made all the more stupid and icky because the season premiere ditched her first season romance with James, a black man, for no reason, only to replace him with a new white love interest. J’onn was given a half-baked plot about finding another survivor of the genocide of the Green Martians by the White Martians called M’gann M’orzz, who’s later revealed to be a White Martian defector posing as a Green. J’onn and M’gann fell in love and then she went back to Mars to try to convince the rest of the White Martians to not be racist, and it was all very bleugh.

Most frustrating was Supergirl’s continued use of cheap thinly-defined female knock-offs of A-list Superman villains in place of the real deal, the obvious and annoying result of setting Supergirl in a world where Superman also exists. The first season featured Kara’s aunt as a female Zod and a lady Brainiac, both bland and eventually overshadowed by Kara’s uncle, a male knock-off of Zod with even less personality than his wife. Some minor Superman foes like Livewire and Silver Banshee made the cut as recurring antagonists, and villains-of-the-week included an undercooked Bizarro-Supergirl and an elderly Toyman, though he’s still a Superman villain and only shows up in Supergirl because Wynn is his son. The second season adapted one B-list Superman enemy as a villain-of-the-week, Parasite, and used Metallo as a henchman to the major villain of its first arc, Lillian Luthor, the fanatically anti-alien mother of Lex. Lillian was succeeded as the main antagonist by a second female Zod, the mother of Kara’s new love interest from Krypton’s “barbarian” sister world of Daxam. As of the end of season two, Mister Mxyzptlk is the only major Superman villain to appear without being pared down into a nothing character or gender-swapped for the sake of gender-swapping, and it’s no coincidence that he’s probably the only good villain the show’s ever done.

Supergirl’s second season had no standout episodes and a lot of problems, especially towards the end of the season. The writers cast Lillian Luthor as the show’s Trump figure in the first half of the season by comparing her fear that alien refugees were the vanguard of an eventual invasion with similar hysteria drummed up by far-right zealots in real life, but the season ends with an invasion of refugees from Daxam. Cat Grant comes back to National City to give a big speech to inspire everyone and describes their leader in Trumpian terms (“they say they want to make our world great again”). Lillian Luthor gets to say “I told you so” to the heroes and no one challenges or disagrees with her. I almost admire the attempt, but the writers of Supergirl don’t have the range to handle the material. They ended up regurgitating racist rhetoric about good refugees vs bad refugees in a show with two lead characters who are refugees from natural disaster (Kara) and genocide (J’onn). That’s a shame when it had much more interesting things to say on a less grandiose scale in its first season, like the scene where Kara and James allude to how society polices the anger of women and black men:

The last scene of the season two finale drags us back to the last moments of Krypton, where we see a third child was sent to Earth with Kara and Clark, a child who appears to be a female version of Doomsday, and so its second season ends just like the first season, with the Zod knock-off defeated and another survivor of Krypton’s destruction on the way, swapping out Mon-El for Lady Doomsday or whatever. Supergirl looks like it might fall into the same cycle of repetition that helped turn The Flash into the crap it is today. But I won’t give up hope just yet. We still have Melissa Benoist on our TVs and that’s enough for now.

Part 2: Stand-Alone DC

Gotham

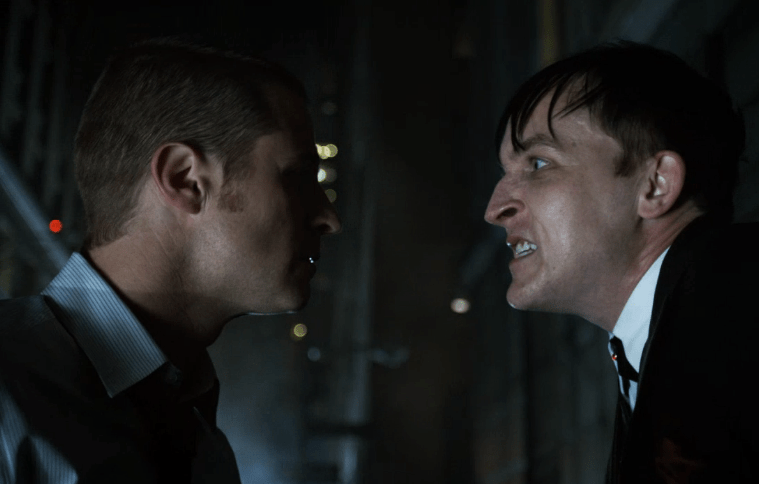

I’ve said it before, dozens of times, and I’ll say it again until it stops being true: Gotham isn’t a good TV show, but it’s fascinating and weird and ambitious and what it does well, it does great. The first season was a horrible experience because there were two to three bad episodes between every good one. But, much like Supergirl, the show had a secret weapon, an actor whose performance made any episode tolerable as long as he appeared, Robin Lord Taylor as Oswald Cobblepot, better known as the Penguin. Taylor isn’t the hammiest actor in Gotham (that’s Erin Richards) or the best (that’s Jada Pinkett Smith), but his performance is the one that feels most true to the character, like it’s not an act or a mask or a persona, like Oswald is really just that much of a psychopathic dork. When you watch a scene like this one, from the first season highlight “Penguin’s Umbrella”, there’s no sense of showmanship on Penguin’s part. If anything, it’s too earnest:

Once the writers dropped season one’s case-of-the-week structure to focus on serialised storytelling and went all on its dark campy mashup of genres, Gotham became one of TV’s strangest gems.

Who needs a tightly-edited straightforward narrative when you can suddenly bring the major antagonist of the season’s first arc back from the dead halfway through the second arc and then blow him up with a bazooka one episode later?

Who needs to honour the source material when you can have Teen Joker with his own severed face stapled to his skull fight Teen Batman with sad clown makeup in a hall of mirrors?

Who needs every scene to be clear and concise when you can have an awkward, meandering and largely one-sided conversation between Alfred and Lucius that’s so funny I sometimes burst out laughing apropos of nothing because I remembered it?

Gotham is so silly and so dark, and I know lots of reviewers don’t think those elements mesh very well, but I think they’ve misunderstood the show. Gotham is about madness and breakdown and the incoherence of identity, it’s a story of people just trying to live in this crazy world until they can’t anymore, and they succumb to it. They stop struggling. They drown in the horror of the world and let it fill their lungs and heart and brain until it stops hurting and starts to feel good, and then they say “I see now who I really am”. That’s what everyone in Gotham says after going over the edge, and whether they were pushed or jumped (usually it’s a bit of both), no one regrets their monstrosity. The heroes are the ones who suffer, because they persist, even when it’s hard, even when it’s hopeless, and that’s the only thing that stops Gotham from collapsing into nihilistic trash. Their struggle with the temptation to just give up and become another villain may be bleak and difficult and less fun than Jada Pinkett Smith’s Eartha Kitt impression but it’s also what gives the show its heart.

Gotham will never be great television (especially since it refuses to write Bruce out of the show until he’s tall enough to be Batman), but it’s never dull either. The cinematography alone makes it a small wonder. Who knows what’ll happen next? I guess it’s the League of Assassins, but they could change their mind halfway through the season and decide it’s time to do Bane instead. Or Maxie Zeus. Or Polka-Dot Man. The future holds all possibilities, except that Bruce might fuck off.

Part 3: Marvel on Netflix

Daredevil

Stop me if this sounds familiar: I loved the first season of Daredevil, but–

I was so excited about this show, but–

Season one was close to perfect, but–

Daredevil is my favourite Marvel superhero. I think the director’s cut of 2003’s Daredevil is a really great movie, with one of my favourite scenes in a superhero film. Matt comes home from a difficult night on the streets. He takes off his suit and gets into the shower. We see his body covered in scars and wounds yet to heal. He puts his finger in his mouth and pulls out a broken bloody tooth, then he just stands under the water, his head hung low in exhaustion. He walks to the sensory deprivation tank where he sleeps to drown out the noise of the city. Daredevil is blind, but his other senses are so powerful he can hear events blocks away from his small dirty apartment. Just as he’s about to get in the tank, he hears someone scream for help. He cocks his ear, and in his mind’s eye, he sees a woman about to get beaten to death. You can see him tense up, but you don’t know whether he’s steeling himself to go back out on the streets or for what happens next: her assailant hits her, hard. Matt listens but all he can hear is the sound of her ragged breath, fading… fading… gone.

Netflix’s Daredevil is just as interested in Matt’s internal struggle. He’s a working-class Catholic lawyer, but every night he stalks the streets to beat criminals into submission. Matt doesn’t have the resources of other superheroes – he doesn’t even make money as a lawyer because he lets his poor clients pay him in punnets of fruit. He believes in the law, but the law doesn’t always deliver justice. The law is corruptible, and that means sometimes the only justice is the justice that finds you in a dark alley on a cold night in Hell’s Kitchen. But he’s conflicted. How can he know if he’s on the side of good? Matt spends a lot of time in the church. He asks Father Lantom to tell him one way or another if he’s doing the right thing, even though he knows he can’t.

That’s not how this works.

Wilson Fisk is working-class too. He wants to save Hell’s Kitchen, but he doesn’t struggle with it. He is a man of pure conviction. He’s organised a coalition of criminal organisations to buy every building in Hell’s Kitchen, raze them to the ground and rebuild on the ashes. Any landlords who won’t sell will be made to sell. Any tenants who won’t leave will be made to leave. Any lawyers who try to stop the evictions will be made to regret it. Wilson Fisk is a monster, but he’s a man too, and you understand his point of view. You understand his pain. When he meets Vanessa, he falls in love with her at first sight, and you want it to work out. You want him to find in her heart whatever is missing in his own.

I could paint a similar portrait of every character in the show – Matt’s law partner Foggy, their secretary Karen, Fisk’s lieutenant Wesley – because all of them are so richly-defined and complex and played to perfection. But Daredevil is about Matt and Fisk, and there’s something tragic about their conflict. Not just because Fisk could be a better man, but because Matt could be a happier one. He doesn’t enjoy violence, or if he does, he hates that about himself. There are lots of ways someone can make the world a better place. No one has to take it all on their shoulders. No one has to do it alone. But Matt can’t share the weight.

That’s not how this works.

The second season is about ninjas.

More to the point, the second season becomes about ninjas, and it’s a painful transformation from where it starts – Matt needs to stop a murderous rampage by a new vigilante called the Punisher. When he finally subdues him, it becomes Matt’s job to defend him in court. If he loses, the case will set a new legal precedent on the prosecution of vigilantes. Those stakes would be heavy enough if Matt was the only other vigilante in the world, but the shared universe does its job for once here, giving a larger political context to the drama that raises the stakes. Everything hinges on Matt and Foggy winning this case. So, naturally, Matt slacks off from legal prep and misses important court dates because his ninja ex-girlfriend Elektra shows up and we’re supposed to believe there’s some deep connection between them that explains why he’d shirk his responsibilities to spend time with her but there’s not even chemistry. If anything, he seems to hate her, until he doesn’t, for no reason, because the plot says so. The case goes to shit, but it’s fine because no one mentions the precedent ever again, and then Matt and Elektra have to fight ninjas. Some other stuff happens to the other characters that’s way more interesting, but none of it is given much attention because it’s way more important that we watch Matt and Elektra fight wave upon wave of faceless ninjas. I think Elektra is also the Ninja Anti-Christ? I don’t care.

Jessica Jones

I hope Jessica Jones gets cancelled because its first season was close to perfect and I don’t want to risk the possibility that five years from now I’ll start another section of another blog post, or maybe an article on a real website, or a book if I’ve really made it, by saying that Jessica Jones was great in its first season, but–

I don’t want Jessica Jones to get cancelled. I want Jessica Jones to have several more excellent seasons. I want Jessica Jones to be a cultural touchstone. I want Jessica Jones to make lists of the best TV show of all time. I want Krysten Ritter to win an Emmy. I want Melissa Rosenberg to win an Emmy. I want Krysten Ritter to win another Emmy and rub it in the face of whoever at ABC was responsible for fucking up Don’t Trust the B—- in Apartment 23.

I just don’t know if there’s any point in hoping for any of that. Agent Carter is the only other show in the shared universe that started good and stayed good, and it was cancelled. Maybe I’d find it easier to hope for the better if it wasn’t the age of the forced crossover. No stand-alone stories! Everything must interact! Look, it’s Batman and Superman on the screen at the same time! Holy cow, the Flash and Supergirl are singing a duet! I can’t believe Doctor Strange is gonna be in a Thor movie!

Jessica Jones is gonna team up with Daredevil, Luke Cage and Iron Fist to take on Sigourney Weaver or something! We should all be so excited that the only good Marvel/Netflix show is about to get all the poison of the shitty shows that share its universe pumped into its veins until every good thing about it is purged from its body to make it fit into a story about fucking ninjas! Who isn’t fucking pumped as hell that Jessica Jones is about to be ripped away from Melissa Rosenberg so the two stupid jerks who made the second season of Daredevil can team her up with these other assholes? Elektra is gonna be in it! Who doesn’t love Elektra? Who doesn’t love crossovers? Who in the whole world isn’t daily shitting themselves in anticipation of The Defenders?

Four shows about young women with PTSD debuted in 2015: iZombie, Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, UnREAL and Jessica Jones. I loved them all. Two years later, iZombie is still great, but not as good as it was in its first season. Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt is still good, but not as great as it was in its first season. UnREAL is a stupid pile of crap.

Jessica Jones is still as good as it was in 2015. Jessica Jones hasn’t been crudely repurposed for This Age of Trump, This Age of Brexit. Jessica Jones hasn’t done three years of mind control villains. Jessica Jones hasn’t become a show about ninjas.

Jessica Jones airs its second season next year.

Luke Cage

The kindest thing I can say about Luke Cage is that I’d forgotten almost everything about it before I sat down to write this article. Once I refreshed my memory, I couldn’t think of anything good about it except the performances of Mahershala Ali as Cottonmouth and Alfre Woodard as Mariah. Not the characters, obviously, just the performances.

I realised three or four episodes into Luke Cage that it was a piece of crap, but I finished the whole first season because I didn’t want anyone to be able to dismiss my criticism by saying I didn’t even watch it all. That was a mistake and the universe punished me for it. Luke Cage is overlong, bloated and self-indulgent, even for a Netflix show. Multiple episodes include long musical performances in Cottonmouth’s nightclub that add nothing to the show. They don’t run concurrently with any major plot developments or enrich the emotions of the scenes around them. David Lynch is self-indulgent, but at least he has the common courtesy to put all the live music in the Twin Peaks revival over the credits.

I don’t know if I could ever run out of problems with Luke Cage, from the most basic level of story up to its awful politics. Late in the season, Luke is shot with a “Judas Bullet” that can pierce his famously bulletproof skin – shrapnel is scattered through his body and he’ll die if it’s not removed. He’s taken by Claire, a nurse who appears in all four Marvel/Netflix shows, to the mad scientist who gave him his superpowers. The scientist explains that Luke’s skin can be made permeable if they drown him in acid first, so they do, and then Claire removes exactly one piece of shrapnel and Luke is fine. The villain of the second half of the season, who shot Luke with the bullet, is a crime lord called Diamondback who’s off-screen until halfway through the season. When he does show up, he’s revealed to be Luke’s previously unmentioned childhood best friend, Willis Stryker, and then, in the same episode, also revealed to be Luke’s half-brother. If someone wrote that in a parody of the worst soap in the world, it’d be too on-the-nose. Luke Cage is made with the ineptitude of the kind of low-budget action movies slapped together by small business owners and middle-aged karate instructors looking to cash in on the VHS boom of the 80s. Ten percent of Luke Cage’s entire runtime is characters repeating exposition from previous episodes, sometimes from the same episode. The other ninety percent is shit, especially the action. The original comics were inspired by blaxploitation movies, and I understand why the creators decided to take the show in a different direction, I just don’t get why they replaced all of its blaxploitation DNA with Miami Connection:

No one in Luke Cage is half as well-defined and coherent as the most minor characters in Daredevil or Jessica Jones, even or especially Luke, who debuted in the latter. I know Mike Colter can act, because I’ve watched The Following, and I know he can play Luke Cage, because I’ve seen Jessica Jones, but given the chance to front his own show, Colter portrays Luke as a man tragically incapable of using facial expressions or tone of voice to convey his emotional state. If he could remember how to act, Mike Colter might have made the show tolerable, but a shoddy performance of the worst script in the world is like getting stabbed with cholera – one or the other, please, but I can’t survive both.

I could go on. The directing is lifeless. The dialogue is cringeworthy. Luke and Cottonmouth have no ideological conflict whatsoever. They both give speeches at a funeral about how they want to Make Harlem Great Again and it’s shot and scored like a moment of triumph for Luke, but their speeches sound exactly the same. Compare that to Daredevil, where Matt and Fisk both want to save Hell’s Kitchen, but believe in different kinds of salvation. Speaking of Daredevil, the actor who plays Shades, a secondary antagonist, based his performance on Charlie Cox as Matt because he wears sunglasses a lot, but it just confused people by making it seem like he was blind when he isn’t.

But the worst thing about this show is its sleazy, cynical exploitation of racial politics.

In both marketing and the show itself, Luke Cage attempts to exploit the mass outrage against the murder of black people in the US by police that entered mainstream political discourse after the murder of Mike Brown by Officer Darren Wilson in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014. The show’s creator, Cheo Coker, told the audience at Comic-Con 2016 that “the world is ready for a bulletproof black man”, and Coker and Colter both used interviews to hype the show’s timeliness and relevance to the political climate. The “bulletproof black man” line was echoed in press for the series, by critics in reviews and in the show itself – Method Man cameos as himself in Luke Cage and talks about how powerful it is to see a bulletproof black man.

But Luke Cage is the most pro-police superhero show ever made. The secondary protagonist, Misty Knight, is a black police detective who believes steadfastly in the law. When she starts to doubts the system late in the series and gets a witness killed by hiding her in her home instead of a safehouse, the show blames Misty for her lack of trust in the system, not the system for destroying it. Whereas Daredevil features Brett Mahoney, the only good cop in New York, Luke Cage features Rafael Scarfe, the only corrupt one. Luke Cage refuses to countenance the mere possibility there could be any systemic problems in American policing. The show doesn’t depict the constant harassment of black citizens by police – no racial profiling or spurious arrests or trumped-up charges – until Diamondback makes it look like Luke is on a killing spree against the police so he can sell them Judas Bullets.

Luke Cage wants you to know that police would never target black people out of hatred, only out of legitimate fear of a bulletproof serial killer. Sure, in the heat of the moment, under pressure, in fear for their lives and mourning the murder of fellow police, an officer might lose his cool and try to beat information out of a black kid. But no police officer would ever crush a man to death because he sold cigarettes on the street or shoot a 12-year-old black boy for playing with a toy gun or kill a pregnant woman who called the police because her home was robbed. No police officers would ever pull a black man over and shoot him seven times because he reached for his license and registration while a four-year-old girl watched from the back seat. That’s not Luke Cage’s America. Bill Clinton didn’t execute an intellectually-disabled black man to win an election in Luke Cage’s America. Five percent of black men aren’t in prison in Luke Cage’s America, and the guards don’t turn off their water and leave them to die by dehydration or boil them alive in showers or kick them and punch them and throw them down stairs until they’re dead. Black children aren’t forced into the criminal justice system for misbehaviour in school that wouldn’t get a white child suspended, no sir, not in Luke Cage’s America.

Luke Cage is supposed to be a hero for these times, but all he does is tell black kids to pull their pants up and lecture other black people on how they don’t live up to the cavalcade of black icons he’s constantly namedropping in a meaningless vomit of sound. Luke Cage says he wants to Make Harlem Great Again, but he never says how. The only person who wants to help Harlem in any specific way is Cottonmouth’s cousin, Mariah, and the show casts her as a villain because she uses some of Cottonmouth’s dirty money to fund her community renewal projects. Who cares? The city council won’t fund her projects – they want Harlem to decline so they can gentrify it. But then Luke declares war on Cottonmouth for no reason and exposes Mariah, and even then she doesn’t actually do anything evil. Mariah doesn’t hurt anyone until she smashes Cottonmouth’s skull to pieces with a mike stand for saying she was asking for it when their uncle raped her as a child. She frames Luke for the murder so she can continue to pursue her life’s working of saving Harlem from gentrification, and she only teams up with Diamondback to kill Luke because she’s afraid he’ll destroy her life’s work in revenge. In the most sickening moment of the show, she uses Black Lives Matter rhetoric to sway the crowd at an anti-police rally (that she instigated by leaking photos of a police beating) into supporting the militarisation of the police (so she can kill Luke Cage and make money for her evil community renewal projects) in less than a minute. The whole scene is so ridiculous that I have to quote it in full:

“Oh, it warms my heart to see you here this evening. My cousin, Cornell Stokes was murdered right where you’re standing, and it pains me to even be here. But it’s necessary. Luke Cage murdered my cousin, and I am not afraid to speak out about it. The man is a liar, he is a menace, and as long as he is running around loose, hiding amongst us, no one is safe.

Now, I know what brought us here tonight. The police putting their hands on yet another young black man. It’s wrong. It is wrong. No doubt about that. But we cannot lose focus here. A cop was killed by this super-powered menace. And our young brother was hurt during their witch-hunt.

Brothers and sisters our world has changed. We have new threats, new terrorists. That woman over in Hell’s Kitchen snapped a man’s neck because he was mind-controlling her. We got a bulletproof murderer on the loose in Harlem with his own twisted sense of justice, putting us all in harm’s way.

Do I trust the cops? Not blindly. We need protection from Luke Cage. We need protection from the other powered people like Luke Cage. He is the real threat! We need to arm our men and women in blue so that they can protect us – truly protect us and never confuse us with those who are the real threat.”

In Luke Cage’s America, protestors against police violence are so stupid and gullible and easily-led that a short speech by a mildly charismatic local politician can turn them into a bunch of Blue Lives Matter die-hards.

I don’t know why Luke Cage was allowed to get away with such sleazy exploitation of the political struggle against state violence, but it’s disgusting. I’d understand more if it was a good show, but it’s not. Luke Cage is the worst superhero show I’ve ever seen, and no matter how many woke things Cheo Coker says in interviews, it’s also one of the most grotesquely conservative. I hate it.

Iron Fist

This is a reflection on the boom, not a reflection on every show born of the boom, so I’ve included this section to tell you about my experience of not watching Iron Fist, the only superhero show I’ve avoided on purpose and not just by chance. My journey began with the announcement of Iron Fist as part of the Marvel/Netflix sub-universe. When I saw it, I thought to myself “ugh, really, Iron Fist? I bet they’re gonna fuck that up”. Just two years later, Iron Fist was released.