Check out previous instalments here.

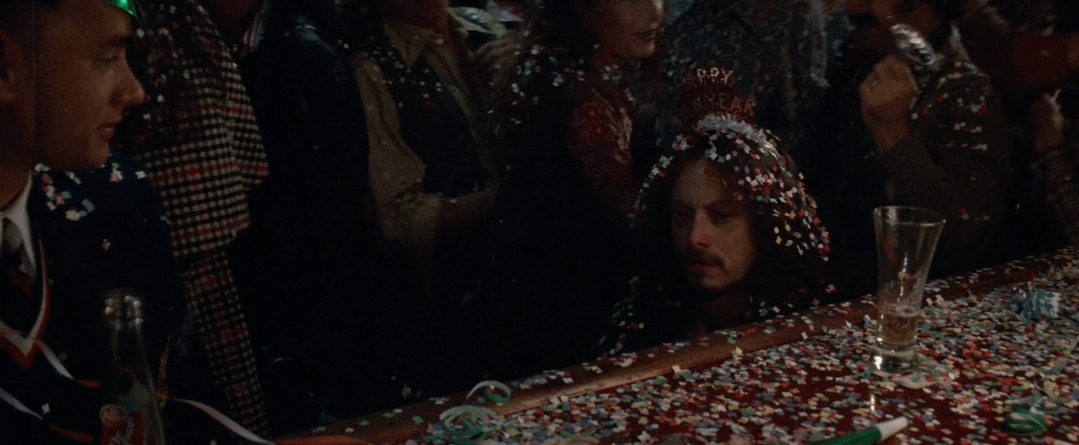

2025 was a year that happened and now it’s over. Ciara completed her PhD and finally watched Tiger King. Dean presented at his first conference and finally finished the second season of China Beach. Along the way, we saw Richard Herring live, and The Pillowman at The Gate Theatre, and did a long-overdue guest episode of our podcast with our friend Conor.

We also watched a lot of films, some of which stuck with us so much we just had to tell you about them. You’ll have to wait until the tenth (TENTH!?) annual Sundae Awards in March for our thoughts on new releases. In the meantime, as ever, please enjoy a selection of our favourite films from this year that didn’t come out this year.

The Buccaneer (1938)

Dean: “The Buccaneer is far and away my favourite film I’ve seen this year, the epic true(ish) story of how a load of scumbag pirates worked together to save America from the Brits – whether America liked it or not! Frederic March leads the film as Jean Lafitte, an idealistic smuggler captain based in a Louisiana swamp who believes that siding with the Yankees in the War of 1812 will give him and his men a chance to escape their life of petty crime and become citizens of this new multicultural republic. Full of adventure, romance, banter and death, nothing gave me the pure undiluted thrill of watching a great movie quite like this.

It is obviously a romanticised telling – the real Lafitte was a brutal slaver, for one – but it’s neither as neat nor as patriotic as I thought it would be, a film more about yearning for a country than loving it. March is extraordinary as Lafitte, and ably backed by Akim Tamiroff as Dominique You and Anthony Quinn as Renato Beluche, but the true star is Franciska Gaal as the sole survivor from an American ship attacked against Lafitte’s express orders. She’s not only the heart and soul of the film, she’s absolutely hilarious, and it blows my mind that she barely acted ever again.”

The Passionate Friends (1949)

Dean: “The Passionate Friends was my first taste of David Lean, and while I’m looking forward to watching some of his epics in the near future, I’m so glad I decided to start with one of his smaller, more intimate films. Ann Todd, Trevor Howard and Claude Rains might not be as incredible a scene trio as Ingrid Bergman, Cary Grant and Claude Rains in Notorious, but they’re a much more compelling love triangle, full of pain and longing.

If Notorious captured something of the world’s weariness after the Second World War, The Passionate Friends captures something of its grief for what might have been, the yearning to have not yet lived through the worst days of your life. The flashback structure, slipping from past to present, prefigures the reveries of Alain Resnais, who would release Hiroshima, mon amour a decade later, but there’s a gentle sadness to its remembering that stands apart.

It’s also very funny that David Lean and Ann Todd met, and began cheating on their spouses with each other, while making a film about marital infidelity.”

The Music Man (1962)

Dean: “I’d seen The Music Man referenced and parodied so many times – from The Simpsons to Crazy Ex-Girlfriend – I expected to find little surprising about it, and in the broad strokes, I was right. Harold Hill is a two-bit con man who travels the country setting up marching bands for youths so he can sell equipment to their parents, then skip town without teaching the kids how to play. His latest target is River City, Iowa, where he causes a moral panic about pool halls to sell the people on his plan, then spends the rest of the film flattering, schmoozing and bamboozling everyone to keep the plates spinning until his pay day arrives.

But, as ever, it’s the telling that makes the story, and The Music Man constantly surprised and delighted me, especially in all the ways its world runs on musical logic the way that comedies often run on cartoon logic. Every time the four members of the school board try to interrogate Hill about his credentials, he tricks them into singing a barbershop song and walks away. Harold is so supernaturally charming he feels almost like some kind of ancient trickster deity living among humans in the guise of a con man, so it’s wonderfully sweet that he finds his humanity by falling for the only person in town who can resist his wiles – unless she’s looking right in his pretty eyes, of course.”

Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion (1970)

Dean: “Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion is one of two Italian films about fascism starring Gian Maria Volonté I watched in a double bill this year. I enjoyed its counterpart, Slap the Monster on Page One, but I adored Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion. Volonté is a police captain about to be promoted to head of the political division, where he will serve as the iron fist of the state, cracking down on political dissidents and social deviants. The day of his promotion, he brutally murders his mistress and deliberately leaves evidence pointing towards himself, just to test the limits of his impunity and see if he truly is ‘above suspicion’.

Volonte’s captain – known as Il Dottore by colleagues – is a vivid portrait of the paradoxes of strength and weakness within the fascist mind, turning on a dime from a bellowing tyrant to a blubbering sycophant when he’s around his own superiors. He can’t even imagine a way to prove his own strength except by proving everyone around him is weaker: submission is the only evidence he accepts. When he feels like he’s getting away with it too easily, he makes himself more and more suspicious, as if the only thing that will sate him is getting away with it after confessing at gun point. Kafkaesque and with a marvelously unsatisfying ending, it’s stuck with me like little else this year.”

Clue (1985)

Dean: “Even though I’d heard that Clue was a fantastic film many times over the years, I watched it with great skepticism. I was willing to believe it was a good film, even surprisingly good, but come on now, fantastic? Worthy of a book about its production? Surely a big screen adaptation of the board game Cluedo couldn’t be a genuine cinematic masterpiece.

And yet, that is exactly what Clue is, a breakneck, laugh-a-minute comedy delight that runs like candied clockwork, bursting with quips, bits, gags and goofs galore. It’s also, even more incredibly, a Cold War satire and a parody of Cold War satires, with a punchline so satisfying I couldn’t breathe from laughing. The stacked cast includes the dream blunt rotation of Christopher Lloyd, Michael McKean and Martin Mull, but no one does it like Tim Curry as the butler, Wadsworth. The sequence where he recaps the entire plot of the movie to that point while sprinting from room to room is one of the best things ever captured in moving images.

When it first played in cinemas, each theatre got one of three different endings, but the home release features all three sequentially, and far from ruining the gimmick, it just makes it even funnier. Communism was a red herring!”

My Left Foot (1989)

Ciara: “My Left Foot sidesteps the familiar tropes of disability representation – paternalistic, pitying, inspirational – by portraying Christy as irritable, depressive, horny, sharp-witted, unromantic, and a great artist neither because nor in spite of his disability. He’s a jerk and I love him. Lots of people may condescend to and underestimate him, but Jim Sheridan’s direction prompts us to identify with Christy before he can even communicate, and so we aren’t trained to pity him just so we can be amazed later. Instead, you get angry at that neighbour calling Christy a dunce. Even though speech therapy plays a major role in the film, there is no ‘cure’ narrative: Christy’s speech gets clearer, but he doesn’t magically not sound disabled anymore.

Daniel Day Lewis is, of course, extraordinary. I cannot even conceive of how we physically performed the role. But it is not just that his body movements or his speech make for a good imitation of cerebral palsy. It’s the total and complete creation of a character on screen. What street in Dublin he grew up on, when he was born, all the times it was suggested to his parents to send him to an institution, every penny candle his mother lit for him, every game of football he lay in goal for – you can feel it all in him, a whole person made of a million moments, as rich and complex as a living, breathing person. I will think about his side profile on the floor next to his dad’s forever.”

The Remains of the Day (1993)

Ciara: “I cry at movies pretty often. Not at the drop of a hat, but regularly enough that I don’t take special notice of it. But when I cry at a movie, the credits roll and I wipe my tears and go along my merry way. What I don’t do, with the sole exception of The Remains of the Day, is continue intermittently weeping for an hour or so after the film ends, muttering to myself about if only they had said something. As if I could fix it, because surely there had been some mistake, to leave things that way.

The Remains of the Day is a tragedy of manners, in which following the rules of propriety and never speaking what is not permitted to be said doesn’t lead to hilarious farce but to emotional devastation. It is beautiful, and horrible, and suffocating, led by career-best performances from Anthony Hopkins and Emma Thompson as the butler and housekeeper in a country estate. They fall in love, and really there should be no problem here, because they are two people of the same class, race and nationality, of equivalent position, and opposite genders. And yet, it is a love that dare not speak its name. This is, in part, because of the totalising emotional labour that compromises domestic service. The never being off the clock. The alienation from one’s own emotions – not just expressing them, but feeling them at all. So when Hopkins lets out one small shout, it feels as big as an earthquake.”

Design for Living (1933) / Y tu mamá también (2001)

Ciara: “I’m a sucker for movies where two best friends are in love with the same girl and, though they haven’t figured it out yet, also each other. Appropriate bonus points for being a screwball comedy or a teen movie. There are Challengers everywhere, for those with eyes to see.”

3 Idiots (2009)

Ciara: “I had always been intimidated by Indian films because Bollywood operates according to its own cinematic grammar, the most distinct in all of world cinema, in which the normative form is a three-hour musical. But I dived in this year, and went on a journey from cringing to enjoying to being sure I was watching one of the best movies ever made. That journey occurred in its entirety while watching 3 Idiots.

It took me awhile to adjust to the rhythms of 3 Idiots. Its humour seemed broad; its insights corny. But it turned out to be one of the great life-affirming sentimental comedy films, a genre that, at its best, has resulted in most of the best-loved films ever made. The story follows several very different students in an engineering college. Free-spirited natural prodigy Rancho (Aamir Khan); Farhan (R. Madhavan) who wants to be a photographer but studies engineering to please his father; Raju (Sharman Joshi) who hopes to lift his family out of poverty. The head of the college, nicknamed “Virus,” believes in treating education as a cutthroat competition. It’s a critique of the Indian education system’s emphasis on a narrow definition of success – you are your grades, and then you are your job – that initially seems fairly generic. Which is why the suicide of a student hits as such a shock. The hard shift from a silly musical sequence to his death is the first key turning point, demonstrating that 3 Idiots has enough on its mind to sustain its seemingly bananas runtime (171 minutes!).

It goes in many unexpected directions from there. But if you groan when they do the hackneyed bit about the astronaut pen – “why didn’t they just use a pencil?” – with apparently zero self-awareness or irony, let me tell you: they pay it the hell off, and you’ll probably cry.”

Ambulance (2022)

Ciara: “Ambulance is Michael Bay’s low-key chamber piece made under pandemic restrictions, so naturally, I could physically feel it make my heart beat faster in my chest. It has a crackerjack premise: two brothers hijack an ambulance with a paramedic inside after robbing a bank, and the chase that makes up the bulk of the film is like if Speed was a heist movie featuring emergency surgery by very-much-not-a-surgeon. As directed by Bay, it’s a showcase for both what repulses people about his movies and what makes him a genius. Bayhem. A kinetic energy that’s relentless and unending, born of Tony Scott and Walter Hill and Jackie Chan, that reaches towards the very essence of cinema. Yes, you do need to see every angle of every explosion. The camera’s constant motion – swooping and orbiting and flying – makes scenes of expository dialogue intense and thrilling. So when that’s happening during an exciting action sequence, oh boy. Is this how people who like Speed Racer feel about Speed Racer?

But on top of that, you have Jake Gyllenhaal giving the performance of his life in the lead. There are shades of Kieran Culkin in his genial freaking out and blasé blowing over, but dialled up to Joker levels. His manic intensity matches the camera’s. Yahya Abdul-Mateen II is a perfect foil as his brother, full of calmness and stoicism and anxiety and moral sense, and their chemistry sells the film’s earnest defence of adopted families, particularly across races, being real family relationships.

Also a random character straight up quotes The Rock, attributing it to The Rock, and if you can’t enjoy the brazenness of that then I don’t know, man.”

excellent rundown on those films that definitely seem like they are worth watching. Well done 👏

LikeLike