No question has dominated pop cultural writing over the last decade as much as this: what do you do when one of your faves is problematic? The situation is obviously a lot more nuanced than that, but that’s the essence of the dilemma, the question that people struggle with. How should you feel, and what should you do, when – not if – the creator of a work of art you love does something evil? How should you feel about them? How should you feel about their work? Should you go see their next film or buy their next book?

Last year, J.K. Rowling publicly confirmed, after years of speculation by fans of her work, that she hates transgender people. Rowling would obviously disagree with this characterisation, but I’m not interested in trying the case against her, I’m just describing my view. She’s often described by critics as a TERF, or trans-exclusionary radical feminist, but I don’t actually think that label is accurate. I remember when the term “TERF” was first popularised, and the entire point of it was to describe a specific kind of transphobic bigot, a radical feminist who denied that trans women are women, not just anyone who uses any kind of feminist rhetoric to justify their hatred. While some figures involved in recent anti-trans political activity in the UK fit that description, the vast majority wouldn’t be caught within a country mile of the actual political tradition of radical feminism. Those that are feminists at all are almost exclusively liberal feminists borrowing the arguments, but not the principles, of genuine TERFs, just as certain elements of the far-right use the contemporary rhetoric of antiracism to advance a white nationalist agenda.

J.K. Rowling is one of those liberal feminists. She’s not a TERF, just a garden-variety bigot trying to coat her hatred in a thin gloss of moral righteousness. I appreciate this might seem like a pedantic point, but I think it’s important to be fair, accurate and precise about people’s political positions, especially those of your political opponents. You can tell Rowling and other anti-trans feminists of her ilk aren’t proper TERFs because they can’t even make their shite arguments as well. They’re just regurgitating dunks they saw on Twitter or Mumsnet, passed on through some massive game of transphobic telephone, without ever understanding the underlying philosophy that motivates them. All their arguments are purely instrumental, just a way to advance the cause, itself motivated by more-or-less unmediated hatred and disgust toward trans people (especially trans women), rather than any even internally coherent set of values or ideas. Not that proper TERFs are less motivated by hatred, exactly, but at least it’s an ethos. These liberal knock-offs (I’m shocked “astroTERF” isn’t a thing yet) say shit like “you can’t just go around changing the definition of womanhood”, because that’s what all the other transphobes – or “gender-critical feminists” – say. But underneath it, even if they were speaking in good faith, it’s doubtful they could elaborate beyond a few more online talking points on how they define womanhood or how trans people’s existence undermines it.

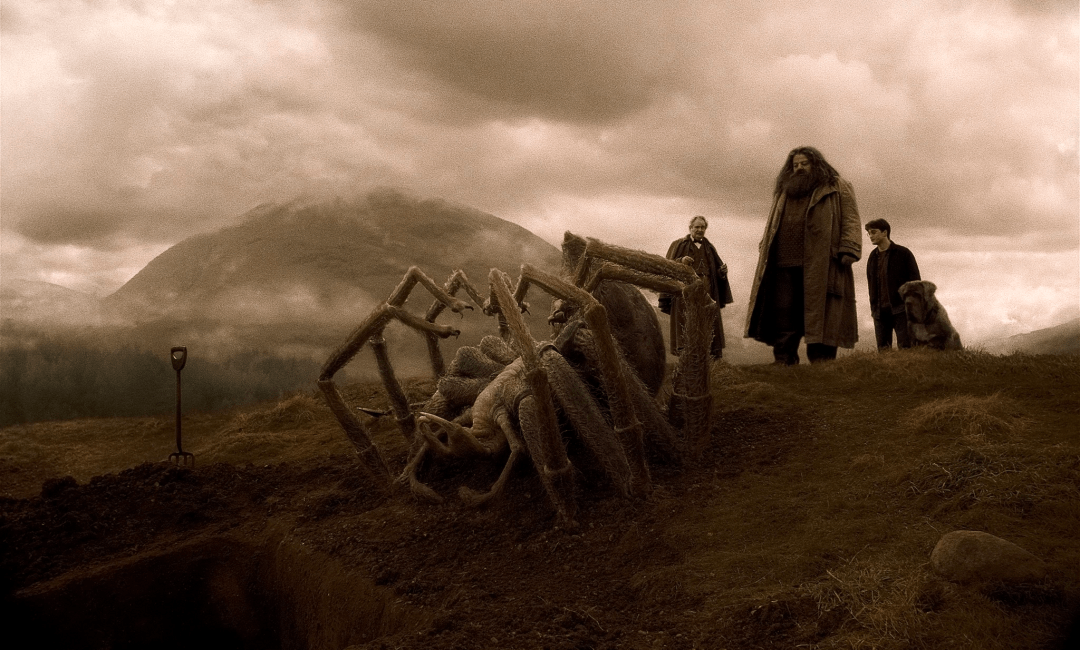

This is not, despite the title, a takedown of J.K. Rowling’s personal bigotry towards trans people or her political activism to curtail efforts to expand their civil rights, access to healthcare and general ability to live safely in a world so hostile to their lives, not least because the definitive takedown already exists. She’s just a useful tool for thinking about the relationship between the art and the artist. Partly because she is, for better or worse, one of the most famous, influential and successful artists of the last fifty years. Partly because her common habit of publicly asserting things about the universe of Harry Potter that aren’t present in the books – e.g. that a Jewish wizard named Anthony Goldstein attended Hogwarts during the events of series or that wizards used to shit on the floor and magic it away until the eighteenth century – has already provoked lots of discussion on whether fans have to accept, believe or give a shit about what Rowling says is true of the world she created. But mostly because she’s been one of a few constant cultural figures my entire life, someone whose works were formative touchstones of my childhood that I returned to regularly up until a few years ago. I even wrote a (not very good) dissertation on them in my final year of college. Every shift in my attitude towards this question of the art and the artist – a topic I’ve been struggling with for years – has been informed at least in part by my changing relationship to both her work and her public persona. I learned how to bury authors from watching her dig her own grave.

Part 1 – Joanne

Continue reading “Burying J.K. Rowling” →