No question has dominated pop cultural writing over the last decade as much as this: what do you do when one of your faves is problematic? The situation is obviously a lot more nuanced than that, but that’s the essence of the dilemma, the question that people struggle with. How should you feel, and what should you do, when – not if – the creator of a work of art you love does something evil? How should you feel about them? How should you feel about their work? Should you go see their next film or buy their next book?

Last year, J.K. Rowling publicly confirmed, after years of speculation by fans of her work, that she hates transgender people. Rowling would obviously disagree with this characterisation, but I’m not interested in trying the case against her, I’m just describing my view. She’s often described by critics as a TERF, or trans-exclusionary radical feminist, but I don’t actually think that label is accurate. I remember when the term “TERF” was first popularised, and the entire point of it was to describe a specific kind of transphobic bigot, a radical feminist who denied that trans women are women, not just anyone who uses any kind of feminist rhetoric to justify their hatred. While some figures involved in recent anti-trans political activity in the UK fit that description, the vast majority wouldn’t be caught within a country mile of the actual political tradition of radical feminism. Those that are feminists at all are almost exclusively liberal feminists borrowing the arguments, but not the principles, of genuine TERFs, just as certain elements of the far-right use the contemporary rhetoric of antiracism to advance a white nationalist agenda.

J.K. Rowling is one of those liberal feminists. She’s not a TERF, just a garden-variety bigot trying to coat her hatred in a thin gloss of moral righteousness. I appreciate this might seem like a pedantic point, but I think it’s important to be fair, accurate and precise about people’s political positions, especially those of your political opponents. You can tell Rowling and other anti-trans feminists of her ilk aren’t proper TERFs because they can’t even make their shite arguments as well. They’re just regurgitating dunks they saw on Twitter or Mumsnet, passed on through some massive game of transphobic telephone, without ever understanding the underlying philosophy that motivates them. All their arguments are purely instrumental, just a way to advance the cause, itself motivated by more-or-less unmediated hatred and disgust toward trans people (especially trans women), rather than any even internally coherent set of values or ideas. Not that proper TERFs are less motivated by hatred, exactly, but at least it’s an ethos. These liberal knock-offs (I’m shocked “astroTERF” isn’t a thing yet) say shit like “you can’t just go around changing the definition of womanhood”, because that’s what all the other transphobes – or “gender-critical feminists” – say. But underneath it, even if they were speaking in good faith, it’s doubtful they could elaborate beyond a few more online talking points on how they define womanhood or how trans people’s existence undermines it.

This is not, despite the title, a takedown of J.K. Rowling’s personal bigotry towards trans people or her political activism to curtail efforts to expand their civil rights, access to healthcare and general ability to live safely in a world so hostile to their lives, not least because the definitive takedown already exists. She’s just a useful tool for thinking about the relationship between the art and the artist. Partly because she is, for better or worse, one of the most famous, influential and successful artists of the last fifty years. Partly because her common habit of publicly asserting things about the universe of Harry Potter that aren’t present in the books – e.g. that a Jewish wizard named Anthony Goldstein attended Hogwarts during the events of series or that wizards used to shit on the floor and magic it away until the eighteenth century – has already provoked lots of discussion on whether fans have to accept, believe or give a shit about what Rowling says is true of the world she created. But mostly because she’s been one of a few constant cultural figures my entire life, someone whose works were formative touchstones of my childhood that I returned to regularly up until a few years ago. I even wrote a (not very good) dissertation on them in my final year of college. Every shift in my attitude towards this question of the art and the artist – a topic I’ve been struggling with for years – has been informed at least in part by my changing relationship to both her work and her public persona. I learned how to bury authors from watching her dig her own grave.

Part 1 – Joanne

The common phrase you hear around discussions around whether it’s okay to still like Harry Potter even though J.K. Rowling is a bigot is “separating the art from the artist”. I’ve really come to hate this phrase over the years. First, and most essentially, because it assumes the art and the artist are attached in the first place without explaining how or why. I’ve been reading criticism and literary theory since I was a teenager and I’ve basically never read a convincing explanation of what exactly the art and the artist have to do with each other except that the latter made the former. I get that connection feels significant: apart from our natural inclination to find causal relationships noteworthy, it’s also taken for granted in our culture that the art and the artist have a connection. But we aren’t taught to feel that way about most other things made by people. Admiring a chair or enjoying a pizza doesn’t come with an expectation of knowing or understanding who made it. In school, we’re taught to read fiction and poetry as a search of the author’s intended meaning, especially with writers like Sylvia Plath, whose work so readily reflects her own biography – lifelong struggles with mental illness, the long shadow of her father’s death when she was eight, the abuse and adultery of her husband, Ted Hughes – that her final work, “Edge”, is often taught more like a suicide note than a poem. Artists are constantly interviewed in the press and asked to explain “the meaning behind” their work or “what it’s really about”, something that seems to have declined somewhat since the insane peaks of a few years ago, when Vulture was essentially letting Aziz Ansari recap his own TV show, but nonetheless constantly positions the artist as special arbiters of reality whose sacred lips alone may dictate the truth of an artwork’s essential nature.

But I also hate the phrase “separating the art from the artist” because I feel like the definite articles and singular nouns – “the art” and “the artist” – while abstracting the idea from any specific case, still imagines the act of separating the art from the artist as something you have to do one at a time, as if every work of art you’ve ever encountered came with some horrible octopus monster attached to it that you have to peel off tentacle by tentacle. Works must always be disentangled from the life, statements, actions, personal beliefs and public persona of authors who’ve done wrong before they can be enjoyed ethically, provided you even believe such a separation is possible. It’s framed almost like psychological work, an internal self-audit of your soul, the same way we might examine and pick apart our relationship with our parents or “unlearn” a bad habit. I get to read Harry Potter, but only as long as I’m constantly aware of J.K. Rowling’s odious beliefs and watch out for the bigotry hidden in her work, lest she plant the dark seed of hatred within me and I wake up a transphobe.

So much of what’s frustrating about these discussions is that they get bogged down in the individual case, debating whether a given artist can be separated from their work, rather than questioning the nature of the relationship itself. This is part of why the “rules” are so inconsistently applied: a very public campaign to boycott the music of R. Kelly, but no similar campaigns to boycott the music of Elvis Presley, Tupac Shakur or David Bowie; Roseanne cancelled because Roseanne Barr did a racist tweet, while The Deuce kept airing with little controversy after James Franco was accused of sexual harassment and assault; Danny Masterson’s career ended overnight while T.J. Miller’s goes on. Whether or not an act of wrongdoing sticks to an artist’s reputation is pretty arbitrary, which just makes it more insane that we’re still apparently trying cases one at a time, weighing up the evidence against each individual artist, combing through their work for detectable impressions of their personal evil and running the moral calculus of continuing to “support” them, a word that can mean anything from paying to see a movie they’re in to watching a pirated version in the privacy of your own home.

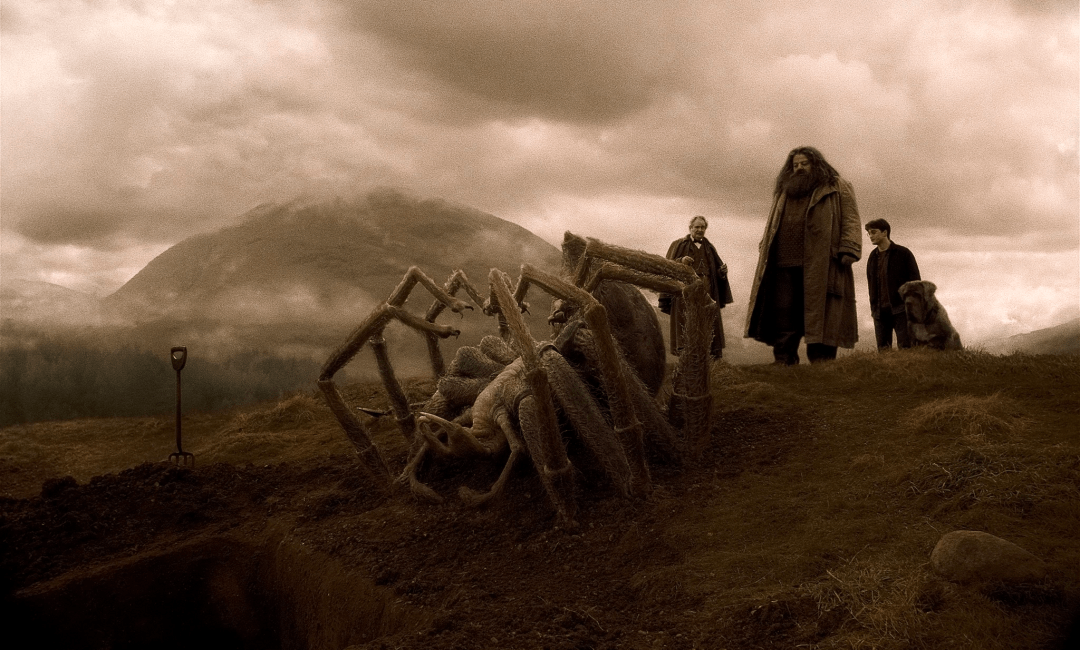

Rowling has attracted controversy and criticism for her public statements and actions before – like when she said the entire Scottish independence movement was just a front for fascism or declined to recast Johnny Depp after allegations of abuse by Amber Heard, his ex-wife – but never anything so widespread as the backlash to her decision to begin publicly advocating against the rights of trans people. I think, for a lot of her former fans, including me, it’s been easy for years to just think of her as an annoying person on Twitter who makes stupid announcements like “Hagrid was too dumb to do a spell all the child heroes could cast” or “Harry named his son after Snape because he felt guilty about everyone who died in the final battle”. Her public persona became extremely embarrassing to watch, but easy enough to ignore, even with the media’s habit of writing up every second thing she tweets as if it’s news. But then she began to alienate fans through her vocal opposition to political causes popular with her primarily millennial readership. She was an outspoken unionist in the 2014 Scottish independence referendum, when voters aged 25-39 were the only age cohort to vote for an independent Scotland. She has a frankly unsettling and obsessive hatred for the overwhelmingly youth-backed Jeremy Corbyn and spent his leadership picking fights with his supporters online. (Just in case you didn’t click the link, she wrote this insane thread in faux-biblical language where she imagines herself as a holy prophet smiting the Corbynites. It features the amazing line “‘Yea, I must speak,’ said she, ‘for when Jews no longer feel safe in Labour I too must leave’.” Just incredible stuff altogether.) Even if you didn’t find her politics disagreeable, it was exhausting how the simple fact of her celebrity turned everything she did online into, if not always news, then certainly a social media topic of the day. She went from embarrassing to irritating and became something of a hate figure in many parts of the Internet. But her decision to pivot – like Graham Linehan before her – from “celebrity who posts too much” to “public hate campaigner” was the straw that broke the camel’s back. Not all the fans who turned on J.K. Rowling over her anti-trans activism were necessarily aware of this background, but for lots of us, it wasn’t so much a break as a final disillusionment.

In the weeks after Rowling very publicly aligned herself with anti-trans activists last year, I saw posts on pretty much every social media platform I use outlining some of the dicey things in Harry Potter readers have taken issue with before – the antisemitism of the goblins, the portrayal of house elves as happy slaves, virtually everything about Cho Chang – and trying to add evidence of transphobia to the list. But the “evidence” of J.K. Rowling’s transphobia is that she keeps saying and doing things to hurt trans people right now, not the books she wrote when Tony Blair was still leader of Labour. Her portrayal of goblins as a race of big-nosed, money-hungry, untrustworthy bankers is uncomfortably similar to how antisemitic propaganda portrays Jews, but nothing in her public statements or actions indicates that her use of antisemitic tropes in Harry Potter reflects her views on Jewish people. The whole point of concepts like learned bias, rape culture and so on is that dangerous, inaccurate and unjust ideas about race, gender, class, age, ethnicity, disability, religion, etc. are so deeply woven into the fabric of our culture that even the most decent, good-hearted, well-intentioned people need to make a conscious effort to not unwittingly express and reinforce these ideas. J.K. Rowling doesn’t need to be personally antisemitic to have a web of cultural associations in her brain that made her portrayal of goblins seem like a good idea at the time. Goblins were commonly portrayed with big noses long before Rowling, like in the art of the pioneering children’s illustrator Arthur Rackham. It may well have seemed like a neat inversion of the standard conventions of western fantasy to have goblins – usually described as little more than animals in the works of Tolkien and his imitators – be industrious and money-hungry instead of the more typical dwarves. We don’t need to assume she thinks Jews are evil. After all, she’s so opposed to Scottish nationalism it verges on outright ethnic hatred, but that’s never come up in her books.

The main cited evidence for transphobia in the Harry Potter books was that Aunt Marge (the cruel sister of Harry’s abusive uncle) is described as having a moustache. Disgust for women with facial hair is obviously rooted in the same binary thinking about gender that underpins disgust for trans women, and I understand that disgust can also affect trans women, in the same way that policing the (alleged or actual) presence of trans women in women’s bathrooms leads to harassment and intimidation of both trans women and gender-non-conforming cis women. But it’s absurdly simplistic to call this evidence of Rowling’s transphobia, especially since it seems pretty likely that she was radicalised online in the last few years. She wrote The Prisoner of Azkaban, the book in which Aunt Marge appears, over twenty years ago. Most people who portray hairy-lipped women in a negative light don’t go onto become anti-trans hate campaigners. And even if you argue it can tell us something about Rowling, it tells us nothing about the books. Their content is what it is, regardless of Rowling’s beliefs, then and now, it doesn’t change because she changes. So what exactly do her beliefs and her works have to do with each other?

Part 2 – Art and the Artist, Again

The answer is usually something about how every work of art is shaped by the specificities of not only the time and place and process of its creation, but the people who do the labour of making it. That’s certainly true. In fact, it’s so true it kind of makes the idea of sole authorship of any work that has been shaped by multiple hands seem faintly ridiculous: back when she took notes from readers and editors, Rowling’s books were informed by their input and therefore, presumably, their beliefs. That doesn’t mean we need to let Rowling off the hook for the content of her books, but it throws a bit of a wrench in the individualistic “separating the art from the artist” concept. Separating the art from the artist in the case of, say, a Roman Polanski film shouldn’t hinge solely on separating it from Roman Polanski, but everyone in front of and behind the camera with a claim to a role in making the film what it is. The actors, the writer, the cinematographer, the editor, the production designer, the storyboard artists, costumers, sound designers, make-up artists, stunt team, effects supervisors, the whole cast and crew. But it never means that, and after years of struggling with this question, how to separate the art from the artist, the reason why is clear.

It’s because “separating the art from the artist” isn’t really a theory or ethos or even attitude about how to interact with art. There’s no logic to it, no reasoning, no principles. It’s just some bizarre folk metaphysics of the relationship between the moral character of an artist and the content of their work stitched together on an ad hoc basis from stuff people read in thinkpieces and posts, heard in video essays and podcasts, or even occasionally sort of half-remember from a literary theory class or media studies seminar. But it adds up to nothing. The whole question is so suffocatingly focused on how to work out your personal feelings about how you relate to the art you engage with, when we should be trying to figure out the correct way to think about art in general. That’s why debates on the ethics of whether or not to listen to someone’s music are so inconsistent: for a combination of social, cultural and individual reasons, way, way more people find it easier to condemn R. Kelly and choose to not listen to “I Believe I Can Fly” and Trapped in the Closet than to condemn David Bowie and choose to not listen to “Life on Mars” and Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps). It betrays a relationship to art so thoroughly degraded by the atomising logic of market capitalism, it can only be conceived of through the lens of whether or not to consume a given work. Whether it’s the question of paying actual money or of simply spending your time on it, it’s imagined as a purchase. That’s why it all feels so bloody arbitrary: who does or doesn’t get “cancelled”, whose work demands an entire thinkpiece cycle of handwringing over whether watching it makes you complicit in their crimes, who is able to make films without anyone ever even considering whether the films reflect how they see the world in some fashion, who is inferred to be a bad person based entirely on the content of their work and who is allowed to get away with being a bad person because the content of their work proves they’re good at heart.

None of these questions are ever answered by some general rule or principle in the endless debate about whether we can separate the art from the artist: it always comes down to people’s subjective sense of what is, what matters, and what they can live with. Whether or not you think J.K. Rowling is a bigot, whether or not Rowling herself matters to you in some way that it weighs on your reading of her books, and whether or not you can live with that weight. These are not unimportant or uninteresting questions. It’s a good thing to try and live ethically, truthfully and happily, just as long as we’re not delusional about the stakes of our individual choices as consumers. The moral scales of nothing but my own comfort with the choices I’ve made will tip on the balance of whether or not I ever watch another Woody Allen film. Those are fine stakes to agonise over, but you can’t generalise them to other people. These are questions for yourself, about yourself, to be answered by yourself. If you believe it is morally urgent that people not spend money on certain products because it financially benefits people who ought not to be enriched, then organise a boycott – and not a hashtag boycott, a real boycott, with specific and achievable demands presented publicly as conditions of suspending or ending the boycott. Do not “boycott” an artist or publisher or whatever by tweeting about why they’re a bad person and saying anyone who “supports” them (however you define that) is a bad person too. It’s no more a “boycott” than wandering aimlessly around a city shouting slogans through a megaphone is a “protest” or running into the wall of a bank over and over is “direct action”. When public discussion about how we should relate to the works of artists who’ve done wrong is so myopically centred on our personal feelings about individual works and individual artists, rather than any actual theory about these relationships, it’s inevitable it would all become so arbitrary. There is perhaps no starker comparison than the reputational trajectories of Joss Whedon and Zack Snyder.

Whedon’s public support for feminism, the popularity of his earlier shows – particularly Buffy the Vampire Slayer – with women, and the beloved female characters and relationships in those shows, gave his public image a feminist gloss that stopped criticism of both the content of his work and his personal behaviour from sticking. By contrast, Zack Snyder has never been particularly politically outspoken nor has he been accused, to the best of my knowledge, of mistreating his employees, but his movies have been accused – fairly or unfairly – of expressing racist, misogynist and even outright fascist ideas, and the fanbase for his early films leaned male. His public image has long had a vaguely right-wing masculinist gloss: one of the filmmakers most often described as “bro” in a pejorative sense, eclipsed only by the even more baffling choice of Christopher Nolan. Based solely on the content of his movies and his interest in making a new adaptation of Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead, he’s often assumed by many to be personally right-wing, either a fascist or libertarian or, confusingly, both.

Snyder had been in conflict with the studio throughout the making of 2017’s Justice League when his daughter Autumn took her life during post-production. He and his wife Deborah, a producer, left the film to focus on their family, and Whedon, already brought in to punch up the script, took over post-production, directed reshoots and supervised a cut of the film that favoured the studio’s vision. Dissatisfied Snyder fans campaigned Warner Bros. to allow him to finish “the Snyder Cut”, which was released this year. Between releases, Ray Fisher, who played the superhero Cyborg in both cuts, accused Whedon of racial discrimination, harassment and abuse during reshoots, supported and facilitated by studio executives who threatened to end Fisher’s career if he went public. It’s too early to say if trying to ruin the life of a promising black actor for daring to stand up for himself will be the final nail in Whedon’s coffin, but his reputation is certainly at rock bottom. Meanwhile, Snyder is enjoying renewed popularity after (among other things) the Snyder Cut was praised for giving Fisher a much larger role.

It feels like an episode that should have exposed just how nonsensical the way we think about these issues has become. Neither reading the values of an artist into their work nor reading the values of a work into its artists are new phenomena, but the increasingly strange dynamics of modern celebrity have made the absurdity of both much more apparent. It’s just speculative bullshit. I’m at an age where a few people I knew in college have a degree of fame as writers or musicians and it’s been extremely weird seeing people who don’t know them at all reverse-engineer assumptions about what they must be like from their work, to watch in real time as people make up imaginary versions of real people in their head to get mad at (or be in love with). I’ve seen people who grew up poor accused of being “trust fund babies”, queer people accused of being straight, and most horrifyingly, people from rural Ireland accused of being from Dublin. But it goes beyond demographics: people imagine entire personalities for them, decide they’re stuck-up or hostile or shy, mutter darkly about what they’re probably doing right now with all the money they imagine they have. It’s sick. It may not be as fucked up as the most recent thing Nicki Minaj fans have done, but parasocial thinking shouldn’t have to be that out of control before we recognise it as unhealthy.

But even if it wasn’t nonsense, even if we exclusively made accurate inferences from art to artist and vice versa, it’s still a meagre, narrow-minded, stunted way to look at art. Critics constantly, correctly complain about the way we’re taught to “understand” art in school, by picking through clues from a poet’s life to figure out what they “really mean” or what their use of certain imagery “represents”, our answers decreed “right” or “wrong” by the authority of the teacher, the textbook and the exam corrector. It teaches us to see art as a riddle to be solved rather than beauty to be basked in, to think every book or movie or song has a “point” it’s trying to convince you of, and that while your opinion of it can differ, there is one, true, real thing it’s actually “about”. It conditions us to expect a work’s meaning can be “confirmed” by some sufficiently credentialed authority, but instead of teachers, we have critics and reviewers, academics and bloggers, and the artists themselves. It doesn’t develop a capacity to actually engage meaningfully with art ourselves, just to “learn” what it’s “really about” from other sources. It’s awful, it’s death, it’s the abolition of aesthetics itself, and it’s also not that much less sophisticated than how contemporary criticism treats works of art as personal statements or actions by artists that should be interpreted through the lens of their lives and beliefs. Either way, you’re letting the person of the artist define the limits of acceptable interpretation, the limits are just more generous when you’re not learning them in a textbook.

Art needs an artist to create it, but not to sustain it. Once it’s been put into the world, it exists of its own accord, and whether we give a shit about who made it, and in what circumstances we give such shits, is entirely up to us. We can care about who financially benefits from our movie ticket and still refuse to let the bastards to tell us how to watch it. One of the reasons I loved studying Old English poetry in college was so many of them were written by authors unknown, so interpretation felt so much freer. “Wulf and Eadwacer” is conventionally interpreted as a woman’s lament for her lover, but if you read the word “hwelp” (whelp, cub or pup) as a metaphor for the product of two people’s love, rather than offspring specifically, the speaker’s gender is left totally ambiguous and it opens up to a reading as a lover’s lament from one man to another. That’s the kind of subversive, reclamatory or exploratory interpretation that’s possible when we attend to the art itself instead of shackling ourselves to the artist.

But the authors don’t need to be unknown: I once wrote a poem from the perspective of a suicide bomber in the moments before she detonates the bomb that a classmate read as a poem about the wedding-day anxieties of a woman who married for money. It wasn’t what I intended, it wasn’t an interpretation that had ever occurred to me, but I read the poem again and there it was. Right there alongside and overlapping with my own interpretation. Artists make art, but people make meaning from it. That doesn’t mean everyone’s opinion is equally valid, their analysis equally rigorous or their conclusions equally fair. It just means we need to stop letting artists dictate the terms of our understanding, whether it’s literally letting them tell us what their work is “about” or insisting on reading it through the lens of their image, life or beliefs. We need to separate all art from all artists altogether.

We need to kill all the authors.

Part 3 – The Living Dead

The term “separating the art from the artist” is often used interchangeably with a concept called “the death of the author”, named for the essay of the same name by the French literary theorist and philosopher Roland Barthes. “The Death of the Author” is somehow both the work of literary theory assigned most often to college literature students and the work comprehended by them least. I’m not a huge fan it myself. I hate the idea academic writing is worthless if it’s too dense and technical for a casual reader, but you’d think an essay that claims to be a revolutionary document could tone it down a little. I don’t think it leaves enough room for the materialism of acknowledging that artists can have styles and habits and so on. The literary references it uses are very inside baseball: it’s not just they’re dated or specific to the field, but that the essay takes for granted it can skip over some of its own reasoning by going “you know, like Mallarmé”. But the theory it proposes is nothing like “separating the art from the artist”: separating the art from the artist presumes a link between the art and the artist that must be severed, the death of the author denies such a link exists at all. The death of the author argues readers – casual and critical alike – should cultivate a radical disregard for the artist when we engage with art, because the idea there’s some link between them that we should be conscious of, let alone guided by in our interpretation, is not just incorrect, it’s actively hostile to the human experience of art itself.

Perhaps appropriately, my favourite demonstration of the validity of the death of the author comes from a writer who doesn’t believe in the death of the author, digital essayist and comic book critic Colin Spacetwinks. Their essay “Comics and Cowardice” is about how both specific artists like Nick Spencer and the comic book industry writ large uses political imagery to gain positive attention as a “serious” medium, but denies political themes or content when critics take them seriously enough to say they’re bad. It’s a pretty familiar dynamic for anyone interested in mediums whose fan and artist cultures have a massive inferiority complex about whether people see them as “real art”, and I like comic books, video games and professional wrestling, so I’ve seen a lot of it. But I’d never thought of it as lying until I read Colin’s essay. And then it all kind of fell into place.

Because Colin’s essay shows the artists are lying about the art by analysing the content of the art itself. The art is what’s true and real and fixed. The art is what we measure statements about it against: if someone tells us a scene in a film that we think is gross is actually romantic, we don’t check by looking for an official statement confirming one way or the other, we put on the scene and try to see it from their point of view. Or at least we should, because the core relationship in art, long before we even had the modern idea of single authors (an extremely new concept, historically speaking), has always been the relationship between the book and the reader, the movie and the watcher, the song and the listener. The author is just a parasocial illusion, a person we imagine we can understand well enough to draw links from their work to their souls, or from their souls to ours, but who isn’t really accessible to us. At the end of the day, our interpretations of works of art are ours and ours alone: they can and should be informed by multiple perspectives, and we should never be so committed to our initial feelings on individual works that we can’t be open to changing our minds later, but they’re ours.

When J.K. Rowling finally went full public bigot, Daniel Radcliffe released a statement of polite but firm disagreement through The Trevor Project, a non-profit focused on suicide prevention among LGBT people. I think the final paragraph is worth quoting in full:

“To all the people who now feel that their experience of the books has been tarnished or diminished, I am deeply sorry for the pain these comments have caused you. I really hope that you don’t entirely lose what was valuable in these stories to you. If these books taught you that love is the strongest force in the universe, capable of overcoming anything; if they taught you that strength is found in diversity, and that dogmatic ideas of pureness lead to the oppression of vulnerable groups; if you believe that a particular character is trans, nonbinary, or gender fluid, or that they are gay or bisexual; if you found anything in these stories that resonated with you and helped you at any time in your life — then that is between you and the book that you read, and it is sacred. And in my opinion nobody can touch that. It means to you what it means to you and I hope that these comments will not taint that too much.”

I think this is a beautiful sentiment: the relationship we have with an artwork, our experience of it through our senses, in a particular time and place and mood, is real in a way our parasocial relationship with their creator isn’t. I was genuinely moved that Radcliffe called it sacred, that he used the opportunity to not only speak out against J.K Rowling, but to affirm to readers that the book is, was and always will be theirs, not hers. But even a lot of people who appreciated Radcliffe speaking out were critical of this portion. They said it was letting people off the hook for still liking Harry Potter, and it made me want to scream. Years of public handwringing over what you should do when your fave is problematic has apparently left a lot of people thinking that the only reason you could ever possibly argue for this point of view is for your own personal comfort, because that’s pretty much all this debate has ever been about for them. But the death of the author doesn’t discriminate: I am as opposed to letting artists I love, like Martin Scorsese, dictate how I interpret their films as those I loathe, like Woody Allen. My first break with J.K. Rowling – long before I ever hated her – was over an interpretation I agreed with. When Rowling first declared Dumbledore was gay, I was elated to have my understanding of the character, how I had interpreted him while reading the final book in particular, “confirmed” by the author. But over time, my feelings about it soured. It’s not that Rowling did nothing to contribute to whether I thought Dumbledore was gay – she wrote the books after all – but I was the one who saw his relationship with Grindelwald, felt a queer undercurrent to it and chose to look at it that way. Overthrowing the dictatorship of the author means we get to read, interpret and analyse the art that enriches our lives in ways that feel true or interesting or just because we want to see what a work looks like through a given lens. It means we can have a conversation about Harry Potter that isn’t about J.K. Rowling. It means we can talk about Aaron Sorkin films and TV shows as something other than direct, explicit statements of Aaron Sorkin’s personal beliefs and Aaron Sorkin’s personal beliefs alone. It means we can stop fucking bullying each other on the Internet over whether or not we listen to certain music just because someone who contributed to it was a prick.

I’m not pretending this is a simple attitude to adopt in a world where we are taught from a young age to think the people who make art are central to its meaning. I disagreed with authors from a young age, studied anonymous poetry and read “The Death of the Author” in college, had someone completely change my understanding of my own work with their interpretation and it still took over a quarter of a century for me to begin to develop an indifference to the cultural authority of the artist. I still struggle with it constantly – I have some impassable mental block around Woody Allen that keeps me from his movies, even though I feel ridiculous – but the exceptions of our personal experience with individual works of art should be considered just that: exceptions, and personal. It’s totally reasonable to not want to engage with works of art that bigots, predators or other kinds of scumbags had a hand in creating, but making morality out of it, trying to create a general obligation to steer clear of art “tainted” by an artist, especially for cultural critics, is absurd.

We shouldn’t be closing off ways of understanding art, we should be opening up new ones, and we’ll never be able to do it as long as everything always has to come back to the bastards who make it. Our culture may be stuck in a posture of deference and worship toward authority, but that doesn’t mean we have to go along with it. It needs to be resisted and dismantled and cast into the rubbish heap of history. We need to continuously strive to banish the long shadow of the author from our minds, from our criticism and from our culture. The author is dead, but the author doesn’t remain dead: the author is a zombie clawing its way out of a grave to eat our brains, something we can’t kill in one go, or even forever, but something we can keep in the ground as long as we commit to killing and burying it over and over. I don’t like “The Death of the Author” very much, but I was always moved by its last line: “The birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the author.”

You might even say that neither can live while the other survives.

3 thoughts on “Burying J.K. Rowling”