It’s been the guts of a year since the height of the boom industry of Ghostbusters (2016) opinion pieces, and, I guess, since Ghostbusters (2016). The thousands upon thousands of words written about Ghostbusters were many things, but mostly they were exhausting. For months before the film was released, the Internet was alight both with backlash against the all-female reboot of Ghostbusters and with subsequent condemnation of the backlash as sexism. Somehow an all-female remake of an eighties comedy about hunting ghosts became a touchstone of socio-political debate in a year where the UK voted to leave the European Union and Donald Trump was elected the American president.

As it turned out, Ghostbusters (2016) is a really bad film. Other than a handful of okay lines (“anti-Irish fence,” “Ghosts from the Past: Both Figuratively and Literally,” “Don’t ever compare me to the Jaws mayor!”), it’s mostly just a series of half-ideas, missed landings, and dragging, poorly-edited improv. The “My cat” / “Mike Hat” bit was apparently strong enough to be quoted in several reviews, but doesn’t work when Chris Hemsworth so clearly enunciated “my cat” in the first place – and is just a G-rated version of a joke as old as dirt, anyway. The film’s characters are paper-thin. Kate McKinnon is wacky, and is clearly going for an early-nineties Jim Carrey rubber-face performance but, unfortunately, can only do one face. Melissa McCarthy is mostly given an endlessly, needlessly recurring bit about wontons to work with. Leslie Jones’s character is so underwritten that her main supposed contribution to the team is from obvious and poorly-integrated reshoots (“I read a lot of non-fiction!”) – almost certainly added in response to criticism of the only black Ghostbuster being the only non-scientist. Kristen Wiig, one of the finest comedic actors working today, is mostly relegated to the straight man. Wiig and McCarthy’s characters rebuilding their friendship is abandoned as a plot point twenty minutes in, only to be suddenly brought up again in the finale, as if to give the illusion that the film is about something.

There was a time when it would have broken my heart to say all of that. I desperately wanted Ghostbusters (2016) to be good. I am (was) a big fan of the remake’s director, Paul Feig: I love Bridesmaids and Freaks and Geeks completely, and I really like Spy and The Heat. I’m a big fan of Wiig and McCarthy. I wasn’t familiar with Kate McKinnon or Leslie Jones’s work, except for McKinnon’s Hillary Clinton impression in a handful of Saturday Night Live sketches, which, aside from being bad impressions, are maybe the finest example of non-medy in existence – comedy that not only fails to make you laugh, but makes you less laughing than you already were. I care a lot about women being given more prominent roles in films, especially in comedies, and I’m keenly aware that just one female-led bomb can undermine efforts to get further female-driven movies made.

And I love Ghostbusters (1984). It’s a maybe-perfect film. It’s wonderfully funny, full of deadpan wit and featuring three exceptional comic performances by three great comic actors – Dan Aykroyd, Harold Ramis and, of course, Bill Murray, in his best purely comedic role. His delivery of “human sacrifice, dogs and cats living together – mass hysteria!” is one of the best things ever captured in motion picture. Here is where I’m probably supposed to say that if I saw Ghostbusters for the first time tomorrow, I wouldn’t like it quite as much. To reduce my love for the movie to nostalgia, as has become a weirdly common way of undermining anyone talking about anything older than 1999 being great art. But that would be a lie.

When the backlash to the remake started, way before its release, I assumed that when people made fun of the self-described fans of the original who rejected the remake on premise alone, we were laughing at the idea that something as universally beloved as Ghostbusters was geeky and counter-cultural. We were laughing at the idea that a bad Ghostbusters movie could ruin your childhood when Ghostbusters II already exists. We were laughing at the idea of “Ghostbusters fans” as a small, niche community instead of the natural state of being for all humanity.

But after the film’s release, I was suddenly on the outside of that we. A lot of people said they really loved Ghostbusters (2016), and I could make a cheap joke about them all being liars, but I was and am happy for them. I have no interest in begrudging anyone a good time at the movies, at least not right now. What I am interested in is the tone with which people celebrated Ghostbusters (2016), and its implications.

“If there is one film that holds a political key to understanding 2016, it is Ghostbusters,” wrote The Guardian, “The movie, and the way it was received and viciously attacked online, told us something vital about the hive mind of the US’s reactionary right.”

Maybe that’s true. There was certainly a sometimes intense and scary misogynistic reaction to the movie, and racist attacks on Leslie Jones, spearheaded by odious slime-person and guy who is famous for reasons I can’t figure out Milo Yiannopoulos. But it’s also true that the chair of Sony’s motion picture division said about backlash to the movie, “It’s the greatest thing that ever happened. Are you kidding me? We’re in the national debate, thank you. Can we please get some more haters to say stupid things?” Comments like this lend credence to the idea that Sony may have artificially inflated the backlash as a marketing gimmick, framing paying to see the film as standing up to misogyny and sexism. At the very least, all the reporters solemnly asking Paul Feig how he feels about his film getting a huge amount of free publicity is a little hard to take seriously.

If Ghostbusters “told us something vital about the hive mind of the US’s reactionary right,” it also told us something about the US’s soft liberal feminism.

When I didn’t like Ghostbusters (2016), when I found myself suddenly outside of the we, I was afraid to mention it on the Internet. I’m a tiny bit afraid to write this article. There are people on Twitter who spend their time searching things so they can tell random strangers that they’re bad people. “Call-out culture” ranges from public shaming to revealing personal information (like addresses) to trying – and sometimes succeeding – to get people fired. Once, having gently poked fun at the “safety pin box” – a prohibitively expensive for-profit subscription service designed to teach white people to be better allies to people of colour – I received a succession of unsolicited replies from strangers, condemning me. There are many people online who spend their time searching keywords on Twitter to find someone, with a handful of followers and almost no influence, to shame. This isn’t exclusively or even predominantly a liberal thing – I encountered the alt-right months before the term came into mainstream use, when I noticed how many of the people calling me complicit in “white genocide” for tweeting about Holocaust Memorial Day had #altright in their bios – but there is a particular sting when people using these tactics justify it with feminist language. These folks are, I’m sure, a tiny minority. But mainstream liberalism can mimic the effects at a more impersonal scale. It’s just good politics to be needlessly mean. Shame is the only education tool we have – and, after all, education is the only gap between you and those you disagree with. It’s only the targeted nature of the attacks that are distasteful, not the rotten core of the impulse. Writing off huge sections of the population – like cheering that Trump voters might lose their health insurance – has become so mainstream that many liberals actively sneer at the idea of empathy. You should care about someone else’s well-being only when they have been deemed worthy of caring about. I should know; I used to be one of those liberals, berating myself for my instinct to empathise with those who didn’t empathise with me.

For the rest of my life, I will, every so often, remember that this McSweeney’s article exists, and it will flabbergast me every time. The article is written from the perspective of someone who claims they don’t like the new Ghostbusters movie for a bunch of reasons that aren’t because it has women in it, acting as a satire of supporters of Bernie Sanders’s campaign for US president. This character is against the new Ghostbusters movie because he’s passionate about Hollywood finance reform. He would rather see a re-release of the 1941 Abbott and Costello movie Hold That Ghost, which doesn’t have any female leads but has “rarely voted against female lead issues.” (Which, aside from anything else, is a bad joke. Surely the article should read like it really is about Ghostbusters, or at least, only gradually reveal that it’s not?)

It continues on like that, and finishes with: “This old black and white movie is cool and I don’t dislike women or hold any weird hidden prejudices against them, I’m just really excited about this old movie a lot of people have seen before.”

Here’s the problem with this article: I do really care about Hollywood finance reform. I think the buyout of studios by corporate conglomerates and the emphasis on tent-pole franchise filmmaking has had negative effects that could be fixed with robust antitrust laws. I do want to wait “for the RIGHT new Ghostbusters movie, not just ANY Ghostbusters movie.” That seems like a self-evidently good idea, because good movies are better than bad ones. I am really excited about old black and white movies that a lot of people have seen before. Bicycle Thieves is just as good as everyone said it would be!

“I also know a couple women who would agree with me on the things I’m saying, so again, I think that proves I’m not sexist or misogynist,” the article’s protagonist assures us. You’re supposed to know he’s full of shit. Of course he’s a misogynist. He claims to believe all those ridiculous things! That I’m a woman and I agree with those ridiculous things means I’m ignorant or a liar or maybe I’m just trying to get boys to like me.

After Ghostbusters (2016) came out, there was a lot of talk about how important it was for little girls, including sharing photos on social media of little girls dressed up as Ghostbusters. “It is important for young girls to realize that they, after all, are a valid part of this society and can be anyone they want to be,” Anna Spiess, who took a viral photo of a girl in a Ghostbusters costume meeting Kristen Wiig, told BuzzFeed, “even a GHOSTBUSTER!” It’s a lovely photo, and the children in it look really happy. It’s important for little girls to see themselves as protagonists in stories. But that common formulation – that girls need to realise that they can be Ghostbusters, or scientists, or presidents – has always felt alien to me.

In that version of the story, little girls see films and TV shows and read books with male protagonists, and a big wall of gender is erected making it impossible for them to really relate. The little girl identifies with some minor female character, and so sees the limits placed on minor characters in herself. She watches Ghostbusters (1984) and she’s either the love interest (Sigourney Weaver) or the secretary (Annie Potts), not a Ghostbuster. That’s not a particularly egregious example, because Potts and Weaver’s characters are both pretty great (although all the times Chris Hemsworth’s character being attractive but insanely dumb in Ghostbusters (2016) was described as “role reversal” would lead you to believe otherwise). But there are more egregious examples, where women and girls are essentially one-dimensional and only exist in relation to men, and the effect is cumulative. If protagonists are usually boys, and you can’t identify with boys, you cease to see yourself as a protagonist.

But I never thought I couldn’t be a Ghostbuster. The Ghostbusters were funny and smart, and I could be those things too. The Ghostbusters were men, sure, but if I had to describe them, “scientists” and “friends” would be a lot higher on the list, and I could be a scientist and a friend. I never had any problem identifying with male characters – I might have identified with them more often, because it’s hard to relate to a cardboard cut-out.

Of course I could be a protagonist. Of course I could be a Ghostbuster. Of course I could be president. The problem that disproportionately seeing men in the centre of stories created was that it meant that since I was at the centre of my story, maybe I couldn’t be a girl. There were some notable exceptions, but many of the girls I saw in stories were often so different to me – either very feminine girls who cared about things that I didn’t, or tomboys who were sometimes more like me but they liked sport and cars and always grew out of it anyway – but there were all different kinds of boys in stories. Lots of them were nothing like me, of course, but some of them were, jagged mixtures of smart and really scared and funny and brave and lonely, and all of that seemed much more important than gender. But it’s the gnawing cumulative effect. Being made to feel alienated from your gender, because you can’t reconcile it with the stories.

The only time I’ve ever read someone articulate that feeling was in Hadley Freeman’s excellent book about eighties movies, Life Moves Pretty Fast. She writes:

Men are generally the protagonists of comedies, because comedies tend to be written by men, so it’s easy to grow up resenting your gender, a little. Why do you have to be a woman? Women are boring. Women are there just to laugh at the men’s jokes, or be the disapproving shrew. Women don’t get the good lines. Women are Margaret Dumont and men are the Marx Brothers, and I like Margaret Dumont… but I prefer clowning to making moues of disapproval at Groucho.

Whenever people talked about Ghostbusters (2016) being important for little girls, I can’t help but imagine a little girl ten years from now, seeing the original film and loving it and finding out there’s another Ghostbusters but with girls and being so excited and then seeing it and – it turns out girls just aren’t very good at ghostbusting, apparently. The only ghost they manage to successfully catch in the whole film, they accidentally let loose, and it ends up killing a man. They don’t even bother inventing storage for the ghosts until the film’s epilogue. The male Ghostbusters caught so many ghosts that they made the cover of Time. Maybe that’s supposed to be some kind of commentary on women’s work going unremunerated, but if so, the women failing to catch any ghosts except the one that they immediately let loose undermines it quite a bit. But mostly, I imagine a little girl watching Ghostbusters (2016) and learning, once again, that women aren’t as funny as men. It hurts to grow up seeing that women are only there to laugh at the men’s jokes or be the disapproving shrew, but at least then the problem is only in how the roles are distributed. Maybe if a woman got the chance, she could be Groucho Marx. I could be funny, if you gave me the chance, if you let me. So it will hurt a hundred times worse to see a woman take centre stage, and learn that she isn’t anywhere near as funny as the boys were when they did Ghostbusters.

Even though this is Ghostbusters with ladies, Chris Hemsworth ends up having as big a part as any of the Ghostbusters, or bigger. A woman can’t be mayor, but she can be the mayor’s assistant. A woman can’t be a police officer. A man creates the Ghostbusters logo, which needs an origin story despite being literally just a cartoon ghost with a circle-backslash symbol around it.

(It’s also directed by a man, which is the most feminist thing of all. Nobody mentions that George Cukor made The Women in 1939.)

But when people talk about this film being important for girls, there is no particular effort to reconcile all of this. That would be fine – I don’t expect anyone to spend as much time thinking about Ghostbusters as I have, and I wouldn’t recommend spending that much time thinking about Ghostbusters to anyone – were it not for the context surrounding it. When people said that Star Wars: The Force Awakens would be important to little girls, it was generally a standalone statement in praise of the movie. Not necessarily always, but since The Force Awakens was generally well-received, saying that it would be important for little girls wasn’t a direct response to anything in particular. But with Ghostbusters, it was a line of argument.

But it only works as a line of argument if the person you’re arguing with is a man.

It’s hard to explain if you haven’t witnessed it yourself, but condemning certain viewpoints as being held predominantly by white, straight men, and then framing anyone who holds those viewpoints as necessarily white, straight men has become a pervasive rhetorical trick in liberal circles. Probably eighty percent of Twitter consists of white people accusing other people of being white in order to discredit their opinions. Shuja Haider’s excellent article about the relationship between cultural identity politics and the alt-right explains, “The eligibility of people to make certain kinds of claims is dependent on the set of criteria that fall into the category of ‘identity.’ […] We’re left with a simple rubric for determining the truth-value of a statement. Who said it, what group do they belong to, and what are members of that group entitled to say?” Richard Roeper received online abuse for giving Ghostbusters (2016) a bad review, because if all debate is evaluated based on identity, than any man who would give Ghostbusters a bad review is being misogynistic. If all politics is identity politics, then all debate is a matter of stacking identities up and comparing the piles – even for something as subjective and frivolous as a professional critic reviewing a comedy blockbuster.

You would think this kind of evaluation would break down when confronted with someone who isn’t white and male holding the opinion that has been designated white and male. But instead, there is a perverse kind of doubling down.

Bernie Bro, a pejorative for supporters of Bernie Sanders, was coined in The Atlantic in October 2015. It was generally used to refer to young, white men who supported Bernie Sanders and said misogynistic things to women on the Internet. What’s interesting reading that original article now is that it never talks about harassing women online: it talks about young men who are idealistic and maybe post too much on Facebook. The characteristics of the Bernie Bro are things like “supports a 15 dollar minimum wage” and “isn’t normally a fan of Vox.” The main thing The Atlantic accuses them of being is idealistic and excitable, which aren’t particularly bad things to be.

But when “Bernie Bro” took off, it wasn’t used as gentle mocking. It was condemnation. This was, initially, probably in response to real problems: there were sexist Sanders supporters, just as there are in any group of men large enough, and tackling sexism is important. But the Bernie Bro was treated as a pervasive problem – that people could only be supporting Bernie because they hate women. That there were no reasons to be sceptical of Hillary Clinton, or just interested in a competitive primary process, other than being opposed to women in power. Never mind that Sanders is more popular with women than with men. If the term “Bernie Bro” ever had a useful application, it very quickly began to disappear when the term was used to dismiss any criticism of Hillary Clinton, regardless of content. It disappeared completely when – often male – Hillary Clinton supporters started calling women who supported Bernie Sanders “Bernie Bros”.

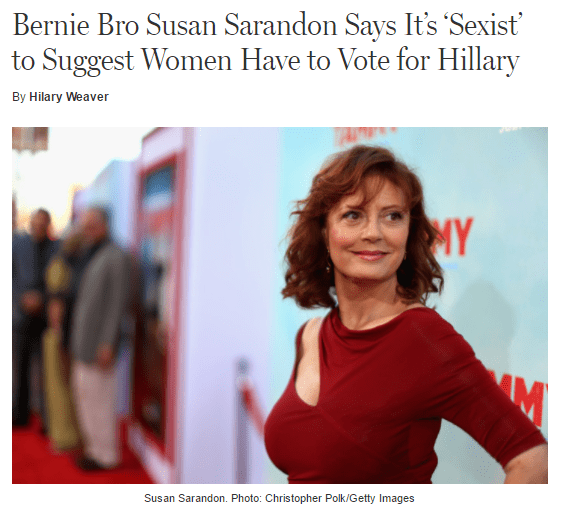

You would think that calling Susan Sarandon a “Bernie Bro” would be a wry, knowing joke, not something that would appear seemingly unironically in a New York magazine headline. Susan Sarandon is a woman, but if she disagrees with you, then you call her a “bro” and her opinion doesn’t matter. It’s one thing to discredit a man by calling them a man, although I don’t like that very much, not least because it pressures otherwise marginalised men to reveal personal information like sexuality or disability in order to prove their “right” to have an opinion. But discrediting a woman by calling her a man, all in the name of feminism, is dystopian.

For a lot of liberals, there are two basic rules: 1. Opinions can be evaluated on the gender of the holder. 2. There are only two genders: people who agree with me and people who don’t.

Only bros like Ghostbusters (1984). Only bros care about getting money out of politics and not bombing the Middle East. Only bros like David Foster Wallace, Quentin Tarantino or the Beatles. Only bros like La La Land, It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia or The Catcher in the Rye. If all this is indistinguishable from misogynists saying only men can like GoodFellas, if it gives me the same anxious feeling in my gut as choosing between the boys’ toy and girls’ toy with your kids meal at a fast food restaurant as a child and somehow knowing that there is no choice, well. Maybe that’s how feminism is supposed to make you feel.

Anita Sarkeesian thinks that Mattie Ross from Joel and Ethan Coen’s True Grit isn’t a feminist character because she acts like a man. Mattie doesn’t display a “range of emotion” and she doesn’t question the validity of capital punishment for her father’s murderer. Sarkeesian says that our male-dominated society values aggression and emotional inexpressiveness, and Mattie just replicates these values. The question of whether Mattie is a “feminist character” is pretty uninteresting, because I’ve never been sure what that’s supposed to mean, but the idea of “acting like men” lays bare something dark and weird.

Women shouldn’t act like men. There was a time when that was a regressive argument against women wearing trousers or drinking beer or working outside the home. Cross your legs. Act ladylike. But if you search “women shouldn’t act like men” here in 2017, you mostly get results about whether it’s feminist for women to “act like men” to get ahead in the workplace. A lot of this stuff is about how women shouldn’t have to change feminine speech patterns and should be able to make taking care of their children a high priority, which is great. But that masculine women find it easier to get ahead in the workplace is unquestioned, even as women are sent home for not wearing high heels to work and two-thirds of employers would be less likely to hire a woman who didn’t wear make-up to a job interview and sixty-one percent would be less likely to promote a woman who didn’t regularly wear make-up at work. Mattie Ross is an unfeminist character for not being emotional or seeking cooperative conflict resolution, and I’m sure it doesn’t help that she wears men’s clothes. Women should behave like women, and let’s not think too much about who decided what that means.

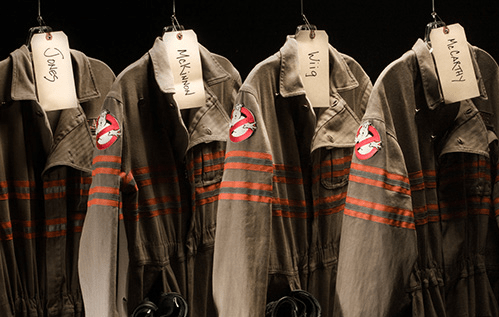

“I wanted for little girls to be able to see themselves up on the screen,” Paul Feig, the director of Ghostbusters (2016) said, “The original one exists, so you can see boys doing it, but how fun for girls to have this experience! […] I’d like girls to be able to put on a proton pack and run around.”

That’s a noble ambition, but I didn’t know girls weren’t allowed put on a proton pack and run around before. As if no girl has ever loved a comedy film, and seen herself in the male characters because that’s all that you can do. I guess nothing has ever embodied hegemonic hypermasculinity as much as a comedy about some schlubby academics becoming exterminators.

But I guess I’m just some bro mansplaining to Paul Feig.

Hey, this one is very old but I just want to say I adore it

LikeLike

Thank you Mark!!

LikeLike