“They say you gotta want it more,” a young man sings in ‘Another Day of Sun’, La La Land’s opening number, “So I bang on every door.”

He came to LA with dreams of making it in the entertainment business, but his problem is not that he doesn’t want it enough. He wants it desperately, single-mindedly. He’s dancing in the middle of a traffic jam, singing about wanting it – as desperately as the dozens of other people singing the same song.

‘Another Day of Sun’ sounds bright and happy, but lyrically, it’s about constant rejection, about running out of money, about leaving loved ones to pursue unrealised dreams – and about a pressure to blame yourself. They say you gotta want it more.

The chorus initially sounds like an ode to perseverance:

And when they let you down

You’ll get up off the ground

‘Cause morning rolls around

And it’s another day of sun

But it’s more melancholy with every repetition, as getting knocked to the ground emerges as a habit. “It’s another day of sun” is a joke about LA not having seasons, but it’s also a comment on how that lack of weather can feel oppressive. It’s an environment that refuses to bend, impervious to your feelings. There’s weariness to it: constant sunshine, constant disappointment.

La La Land is not a film about how you should pursue your dreams.

The willingness of critics, entertainment journalists, bloggers and thinkpiece writers – those who liked the film and those who didn’t – to take at face value that La La Land is a straightforward celebration of single-minded ambition baffles me. It’s partly because (mostly superficial) arguments about the politics of nostalgia and jazz managed to swallow up everything else, but it’s still odd, how one of the most written-about films of the last few years could have so few people take seriously that it might have more to say about its central theme than “dreams are good.”

Whiplash, writer-director Damien Chazelle’s previous film which centred on a jazz drummer at a prestigious conservatory, suffered a similar kind of fate. “The real subject matter of Whiplash is the nebulous boundary between mentorship and abuse,” Salon claimed in a typical article from when the film was released. That’s not true at all, because the behaviour of J.K. Simmons’s character is unambiguously abusive from the start of the film. But it’s easier to write a hot take on a simplistic, repulsive question like “is verbal and physical abuse by a teacher actually not only okay but actively good if you became a great musician?” than to wrangle with a complicated question like “is it possible to still find fulfilment in art if your artistic ability is, in large part, the result of abuse?”

Like Whiplash, La La Land is about the uneasy relationship between art and ambition, and between artistic ambition and the rest of human life. At its most basic, Mia (Emma Stone) and Sebastian (Ryan Gosling) have to choose between romantic love and artistic careers. The common conception is that while Whiplash, with its bloodied-knuckled protagonist practising drums, tries to take the problem of art and ambition seriously, La La Land is a bit guileless. “Rarely has the story [of a small-town girl who comes to Hollywood to make it in the film industry] been told with so little edge or satire,” Michael Green writes in Bright Lights (before comparing it to Sunset Boulevard for some reason, as if “not as good as a Billy Wilder film” isn’t a review you could justifiably give to almost everything), “La La Land takes a few tired shots at the industry – the screenwriter who talks exclusively about himself, the casting agents who never look up from their phones – but is ultimately only interested in the happy ending.”

Here’s the problem: La La Land doesn’t have a happy ending. The five years later epilogue, in which Sebastian has his own jazz club and Mia has become an international movie star and married another man, is a sucker punch. When they see each other again, when Mia goes to Sebastian’s jazz club, they share a what-if fantasy where they stay together, essentially a retelling of the story in a more traditional Hollywood musical, and it’s absolutely beautiful and how it fizzes with joy just makes the real ending all the more melancholy. Mia and Sebastian smile at one another, wistful, and then part ways.

Some people have tied themselves in knots to claim that La La Land’s ending is happy, but that only works if you read the film with logic instead of feelings: the characters got everything they said they wanted, so it’s a happy ending! That means lightly writing off huge chunks of the film, like Vulture claiming, “La La Land ultimately is not about Mia and Sebastian’s romance. The real romance was with the shimmer of dreams.” It means refusing to engage with the emotional reality of the fantasy sequence, pretending to find Mia’s husband more compelling than just a generic nice man, and wilfully misreading her and Seb’s smiles as something as uncomplicated as “We did it! We achieved our dreams!” It means buying into the idea that it is inevitable that relationships stand in the way of creative fulfilment.

Martin Scorsese’s 1977 film New York, New York is also about the tension between romance and career, and it’s clearly a big influence on La La Land. Like La La Land, New York, New York is an attempt to fuse an old-fashioned MGM musical with modern method acting, concerned with a romance between a jazz musician and a performer. The stars of New York, New York are Robert De Niro and Liza Minnelli, and there’s some correlation between them and Gosling and Stone: Robert De Niro and Ryan Gosling are both primarily influenced by Marlon Brando (with Ryan Gosling modelling his accent on Brando’s), and Emma Stone was playing Liza Minnelli’s part in Cabaret on Broadway when she was cast in La La Land. New York, New York, like La La Land, ends with an elaborate traditional musical sequence, and the two main characters briefly seeing one another before parting ways. But in New York, New York, though the ending is tempered with melancholy, the point isn’t that love and ambition are inherently at odds, but that they are here because of the unwillingness of Robert De Niro’s character to accept that his wife could have any wants or ambitions beyond her relationship to him, and his resentment of her success. None of that is the case between Sebastian and Mia.

Instead, La La Land seems to draw on the behind-the-scenes of New York, New York and its fallout. Scorsese was so upset by the failure of New York, New York that he was going to quit the movie business, but was convinced to give it one last try when Robert De Niro came to him with Raging Bull; in La La Land, Mia is so upset by the failure of her one-woman show that she quits the movie business, but Sebastian convinces her to give it one last try when she gets called for a big audition. Mia and Sebastian move from corresponding to the characters played by De Niro and Minnelli, to Scorsese and De Niro themselves: a legendary creative collaboration between two old friends.

Being able to pursue creative fulfilment while being with the person you love is not a lofty goal. Those things are, in their basic form, very simple human wants and needs. They are not intrinsically incompatible: not even close. The two most common reactions to the ending of La La Land that I’ve come across are bittersweet joy because Mia and Seb have correctly sacrificed their relationship for the bigger dream of professional creative success, or frustration that there were no real obstacles that kept them apart. I don’t agree with either, but they’re both half-true, like the blind men describing the elephant. Mia and Sebastian sacrificed their relationship for their careers, and they, I suppose, needed to in order to attain the type of success they have in the epilogue. But they shouldn’t have needed to.

The most important scene in La La Land, the one nobody talks about, is of Sebastian listening to Mia talk on the phone to her mother in the hallway. She’s talking about her plans for a one-woman show (“I’m not getting paid. I’m paying to do it”) when her mother asks about Sebastian, though we only hear Mia’s side of the call.

“He’s going to open his own jazz club. Yeah, it’s going to be incredible.” She pauses, is more sheepish when she says, “No, he hasn’t opened it yet.” Pause. “He’s saving up. I think.”

Seb is buttoning the top button on his shirt and fussing with his tie, and his fond smile fades into something else. He’s looking up at the stain on his ceiling.

Mia tells her mother in a more hushed voice, “He doesn’t have a steady gig. He’s figuring it out, it’s just been a little tricky lately.” Then, more confident, “He’s going to find a way to open it and you’re going to love it, okay? How’s dad?”

I saw La La Land in the cinema three times. It’s a film I love, and a film I’ve thought a lot about. But for all the impressive work on show, I always think back to that ceiling stain. To the way Ryan Gosling’s expression changes – from the easy smile of someone in the bloom of love to something concerned and uncertain – when he hears Mia talk him. It’s not surface-level obvious that La La Land is about money, but more and more, when I think about what La La Land has to say about art and ambition, I think about what it has to say about money. I think about Seb looking up at that stain on his ceiling.

Whether or not you think the film does a good job of establishing it, Sebastian’s relative poverty is basic tenet of La La Land’s fiction. Mia is younger than him, and although she works, it’s pretty implicit that she’s receiving financial support from her parents. Sebastian’s financial situation is much more precarious, and this is established from the outset: while his apartment is by no means in a slum, the size differential between it and Mia’s is very deliberate. His sister admonishes him, “Do you think mom or dad would call this a home?”, “You’re driving without insurance,” “Unpaid bills are not romantic.” When Seb threatens to change his locks, she tells him that he can’t afford it.

“You’re acting like life’s got me on the ropes. I want to be on the ropes, okay?” Sebastian tells her, “I’m letting life hit me until it gets tired. Then I’m gonna hit back. It’s a classic rope-a-dope.”

All of that is before Sebastian gets fired. He plays Christmas songs at a restaurant, a job he clearly finds demoralising, but one he’s glad to have. He tries a funny, sad little negotiation to get to rotate in some of the jazz music that he loves to play (“How about two for you, one for me? How about all for you and none for me?”) but his boss has all the power in the situation. No matter how often you describe employment as an agreement freely entered by two parties, the employee is the one who needs a job to live, and the employer is the one who can take advantage of that. Sebastian puts his own money in the tip jar, and he plays ‘Deck the Halls’ or whatever. Nobody’s listening, and in a moment of daring, he plays some of what his boss calls “the free jazz,” trying to wring some joy out of his situation. After all, no-one is listening.

He immediately gets fired. He begs in hushed tones to keep the job: “What you mean is, play the set list. It’s a warning… Don’t fire me. Don’t fire me. It’s Christmas.”

Later, he plays keyboards in an eighties cover band, costumes and all. Apart from some bum singing, they sound great, but it’s worlds away from what Sebastian wants to be doing. His grand romantic dream is to own a jazz club – to, essentially, have job security, doing what he loves. To be able to play “pure” jazz and not get fired.

Meanwhile, Mia is auditioning for TV and films, and it’s routinely humiliating. She’ll be delivering an intense, moving performance, and the casting director isn’t even looking at her. She walks back into the hallway, to scores of girls who look like her and are dressed like her. “I’ve been to a million auditions, and the same thing happens every time,” Mia says, “Where I get interrupted because someone wants to get a sandwich. Or I’m crying, and they start laughing… I think it hurts a little bit too much.”

In La La Land, employers and potential employers either humiliate or demoralise you. And even then, they pay you so little, you’re either dependent on outside sources of income, or you can’t afford insurance on your car.

Sebastian takes a job with Keith (John Legend), an old frenemy who loves jazz but without Sebastian’s rigid traditionalism. He takes the job as a direct response to overhearing the faltering in Mia’s voice when she tells her mother that he’s unemployed (it cuts straight from the ceiling stain scene to Seb going to Keith’s studio). The job in Keith’s band represents financial stability and a steady job. Seb’s eyes practically bug out of his head when Keith says he’ll be paid a thousand bucks a week – he’s so shocked he can barely choke out his agreement, and it’s obvious he would have done it for a lot, lot less.

A lot of people seem to think that because Sebastian doesn’t enjoy playing in Keith’s pop/jazz-fusion band, the film believes that Keith’s band is some kind of affront to good taste and is obviously “selling out” (an idea that is weirdly ascribed to being a core conflict in La La Land’s story, even though Sebastian plays music he doesn’t enjoy for money long before the audience meets Keith, and Keith himself likes and believes in the music he’s making more than he would “playing for ninety-year-olds at the Lighthouse”). Part of this is the weird insistence in some quarters that unless a protagonist is as overtly terrible as the characters of It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, a work of art straightforwardly endorses everything that character believes. We’re supposed to like Sebastian – he’s funny and charming and passionate – but that doesn’t mean we’re supposed to mindlessly agree with everything he says. Everybody knows that in practice, which is why critics of La La Land have no problem calling it an unambiguous love letter to Los Angeles even though Sebastian says that, in LA, “they worship everything and they value nothing.” That you could be supposed to find Sebastian’s self-seriousness comic and still want for him to be able to play the music that makes him happy – that we could enjoy the music Keith’s band makes, but understand why it isn’t what Sebastian wants to do – isn’t any kind of inconsistency.

“Even though it was different from what Sebastian might have done, [Chazelle] wanted it to be a credible path and credible choice to make your career,” John Legend explained, “He wanted the song to be actually good and listenable and enjoyable, but clearly not what Sebastian was aiming for stylistically.”

It’s not a judgment on the film’s behalf about the future of jazz, but a natural reaction from Sebastian’s character, that playing in Keith’s band makes him want to die. He’s doing really well by external standards of society, but he’s deeply unhappy, and his brain and his heart are at war.

“This is the dream!” he insists to Mia, and to himself, “Guys like me work their whole lives to be in something that’s successful, that people like.”

It’s abstracted and impersonal: the dream, not my dream, guys like me, not I.

So many critics of La La Land have re-imposed those same external standards onto Sebastian, furious with him for not being sufficiently happy, locked into a job he doesn’t find fulfilling. “The movie’s big plot involves Seb’s unhappiness at his good fortune.” Some even bring up the cost of the keyboard he plays in the concert scene. It seems spectacularly unfair, to not take Sebastian’s pain seriously on its own terms, like reading The Catcher in the Rye and dismissing Holden’s depression as whining. But even if you refuse to engage with Sebastian’s feelings, the insistence that he should be grateful for the work points to something insidious.

That being miserable at an unfulfilling job in order to pay the bills is a rich white person problem is one of the weirdest assertions to become as ubiquitous as it did during the La La Land thinkpiece boom. The implication was that poor people or people of colour don’t hate their jobs because they’re glad to have them – that not overflowing with gratitude for the opportunity to sell your labour is privilege in action. But lots of poor people have unfulfilling jobs that make them unhappy. It’s a situation that poor people are much more likely to be in, because not taking a job you would find unfulfilling is privilege: I laugh whenever Ask a Manager tells letter writers to think about if they would want to work for a company that mistreats them so, never mentioning that, for most people, that isn’t a question they have the luxury to ask. But, for critics of La La Land, Sebastian isn’t allowed to not enjoy his job: “The exploiting class exploits the oppressed class solely and exclusively in the interest of the exploited class itself; and if the latter fails to appreciate this, and even becomes rebellious, it thereby shows the basest ingratitude to its benefactors, the exploiters.”

There’s a contradiction there, between the insistence that La La Land has a happy ending because the characters are successful in their careers and that being unhappy with your employment is trivial nonsense, but these ideas come up over and over again. The idea is that the sum of a human life is work: that sacrifices made for personal career success are unambiguously worthwhile, and that gratitude is expected for any work you’re given, because not having the opportunity to sell your labour means your life is nothing.

Second-wave feminists rightfully insisted on the right of women to be able to pursue fulfilment outside of the roles of wife and mother. Somewhere along the way – due, doubtlessly, to a combination of wage stagnation from the 1970s onward and the permanent shift rightwards of the goalposts of Western politics with the elections of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher – this mutated into the strangely mainstream idea that work should be the primary source of fulfilment for everyone. That’s always kind of existed, for men at least – who answers the question of “What do you do?” with anything but their job? I remember someone saying once, to make your answer something more personal and interesting, saying “I’m working my way through the Vatican’s list of recommended films” or “I’ve been trying to visit more museums lately.” But if you tried, the questioner would, of course, clarify: “Oh, I meant, what’s your job?”

Your work is your life, which is why you see such distain for people who take the breaks they’re entitled to and don’t do unrequested overtime, or the concerns of young professionals having to stay late regularly and be constantly on-call getting dismissed with a “welcome to the working world.” In the US in 2014, fifty percent of Americans in full-time employment worked more than forty hours a week – twenty-one percent between fifty and fifty-nine hours, and eighteen percent sixty or more hours a week. There’s nothing wrong with finding fulfilment in your work, but work as the default centre degrades so much else of value in human life: friendship, family, romantic relationships, charity, an assortment of hobbies and entertainments, religion, art. Where does it fit in if you work more than forty hours a week, plus commuting, email-checking, housework? Where does any of it fit in if you’re a so-called gig worker who needs to make yourself constantly available for work that might never come?

A.O. Scott wrote that La La Land shows that “the drive for professional success is, for young people at the present time, both more realistic and more romantic than the pursuit of boy-meets-girl happily-ever-after. Love is contingent. Art is commitment.” He’s not wrong, but I think a film can show something to be the case without endorsing it.

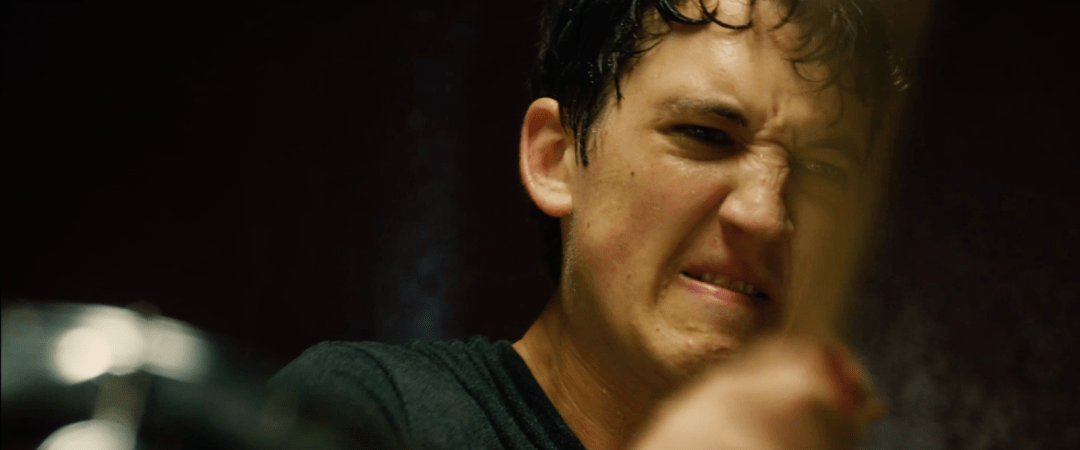

In Whiplash, Andrew (Miles Teller) makes his entire life about jazz drumming, and he’s crushed under the weight. He breaks up with his girlfriend with a robotic lack of emotion. The single-minded pursuit of artistic greatness leaves his body and mind scarred, and his life empty. “Andrew and Fletcher are all competitive id. They aim for greatness,” Colin Biggs wrote for Cut Print Film (in one of the few articles that seems to read La La Land the same way that I do), “Everything else, including human contact, is secondary.”

It’s less dramatic a statement in La La Land, because Sebastian and Mia aren’t in Andrew’s extreme circumstances. La La Land isn’t against artistic ambition inherently: that would be ironic because it is, itself, an ambitious work of art. But it is, in a small way, a cautionary tale. Mia and Sebastian both orientate their lives around a single goal – her, to be a film star, him, to own his own jazz club – because that is what is expected of them, of anyone who is seriously about the pursuit. They say you gotta want it more.

But in a better world, Mia and Sebastian could have dared to ask for a richer life. In the fantasy sequence, the main point of departure is that Sebastian can turn down Keith’s offer of a job – a job he took because he was ashamed of his unemployment – and can go to Paris with Mia and play jazz. In the fantasy, he doesn’t get his jazz club, but it doesn’t matter, because the fantasy is in a world where he can play the music he loves anyway.

3 thoughts on “All We’re Looking for Is Love from Someone Else”