Check out previous installments here.

2023 was a long, long year, and now it’s over. Ciara started lecturing and became chief film critic of Current Affairs. Dean started writing again and became an uncle. We saw Fern Brady at Vicar Street, Fun Home at the Gate Theatre and McFly at the Point. Dean watched more films this year than ever before, but still less than half of what Ciara watched. Ciara has now done enough themed film months to do a whole month of films that didn’t make the cut (July Jumble). Ciara was finally diagnosed with epilepsy after years of struggle against a biased, failing healthcare system, and Dean was finally diagnosed with hypermobility after years of physiotherapists just not noticing somehow. Ciara now lives in a real apartment with rooms and everything, and Dean’s roof doesn’t have a hole in it for the first time in two years.

We did a really fun and very good miniseries for our podcast called Love at Worst Sight and had our first, second and third guests. We talked about Halloween III: Season of the Witch with our friends at The 250, and also recorded an episode on Winnie-the-Pooh: Blood and Honey coming out next year, which does sadly mean that, yes, we’ve both seen Winnie-the-Pooh: Bloody and Honey. Please keep us in your thoughts. Ciara also got published in a bunch more places and presented papers at several conferences, while Dean spent over thirty euro on a taxi to crash on someone’s couch just to see The People’s Joker.

As ever, we’ll be singing the praises of our favourite films released in 2023 in March, for the eighth annual Sundae Film Awards. Right now, we want to look back at the best films we watched for the first time this year, from silent dramas at the dawn of cinema to Jason Statham films released post-COVID. We’ve never had more films to choose from, and whittling them down to just eight each was painful. It was so tough we couldn’t even fit any films from the seventies, and we love films from the seventies. Until next year, here’s the movies we just had to tell you about.

The Outlaw and His Wife (1918)

Dean: “Every year, I watch more Victor Sjöström films and catch myself thinking shit like ‘all cinema is just footnotes to Sjöström’ for weeks afterwards. And who’s to say I’m even wrong? Ingmar Bergman certainly wouldn’t. The Outlaw and His Wife is my favourite Sjöström film so far. Based on the life of Icelandic outlaw Eyvind of the Mountains and his wife Halla, it is both a gripping romantic tragedy and a breathtaking visual spectacle, full of jawdropping shots of the natural landscape of northern Sweden, standing in for Iceland. You can almost feel the chill of the winter winds buffeting the cliff face, the heat of the scalding steam billowing from the geysers.

Sjöström himself takes the lead role, as he often did in his early films, and his performance handily eclipses even his work in Terje Vigen and The Phantom Carriage. His resolute will and righteous fury sear off the screen, which just makes his genuine and lasting love for Halla all the sweeter. But he’s still outshone by Edith Erastoff as Halla, particularly gutwrenching in the scene where their mountain camp is attacked shortly after the birth of their child. I watched this film all the way back in April and I’ve thought about it every day since.”

Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943)

Dean: “I watched Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man as part of my ongoing journey through the works of Béla Lugosi and Boris Karloff, but I loved it because of Lon Chaney, Jr. Despite second billing in the title, this is way more of a sequel to The Wolf Man than any Frankenstein film, and rightly so. Chaney is the only actor to play all four classic Universal Monsters – he’s also been Dracula, Frankenstein’s Creature and the Mummy – but he never gets to flex his incredible gift for pathos quite like he does as Larry Talbot, the Wolf Man, and never more so than in this film.

Larry is always a tragic, pitiful figure, but here his melancholy is the most richly hued, especially in the surrogate parent-child relationship he develops with the gypsy fortune-teller Maleva, mother of the werewolf who bit and cursed Larry in the first film. Despite being one of the first cynical cash-in crossover films in Hollywood history, it’s also a disarmingly thoughtful and moving horror film, with thorny questions of medical ethics raised by both Larry’s quest for a cure and the fate of the degenerated Creature in the last act. It’s a shame the rest of the ‘monster rallies’ aren’t as good, but at least we’ll always have Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man.”

The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943)

Ciara: “Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger were some of the best ever to do it, and The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp is my new favourite film of theirs (with apologies to The Red Shoes). Despite its nearly three-hour running time, I’m astonished all that fits into Colonel Blimp: it doesn’t feel like a long movie, it feels like a life. And by extension, the life of two nations – Britain and Germany – across half a century.

During the Boer War, Clive Wynne-Candy (Roger Livesey) goes to Germany to counter anti-British ‘propaganda’ – while he’s on leave. Even though he’s seen battle, he remains a wide-eyed innocent, a good soldier who earnestly believes in Britain. And more, that right is might and the good guys always win. It is in Berlin that he ends up duelling and then becoming best friends with Theo Kretschmar-Schuldorff (Anton Walbrook), the extent of whose English is ‘thank you very much.’ And that he ends up falling in love, but not realising it until it’s too late: Edith Hunter, played by Deborah Kerr, who recurs in a series of different roles like Meg Ryan in Joe vs. the Volcano. He is haunted by this love; she follows him around.

We follow Clive and Theo and whoever Deborah Kerr is playing this time around through World War I and into World War II, as their countries are on opposite sides of greater conflicts than they have ever seen. By the time World War II comes along, there’s something futile, wistful even, in Clive’s stubborn belief that the good guys will win. A sense that there now exists greater foes than he knows how to fight.”

Pillow Talk (1959)

Ciara: “Pillow Talk, Rock Hudson and Doris Day’s first joint together, is a wonder. A perfectly constructed farce nestled in the all-too-overlooked sexual revolution of the 1950s, history’s horniest decade. Director Michael Gordon uses split-screen to follow the letter but not the spirit of the Hays Code in the most audacious way possible: Day and Hudson are both in the bath in their own respective apartments on either side of the screen, sexily sharing a bath through the power of movie magic.

Day plays Jan, a self-possessed interior decorator in New York. She shares a phone line with Brad Allen (Hudson), a playboy who hogs the line to chat up a seemingly endless parade of ladies. Over the phone, she hates this guy. He’s a total cad. When they meet in person – he knows who she is, she doesn’t know who he is – he affects a persona: Rex Stetson, fresh of the boat from Texas. Shenanigans ensue accordingly. There’s a whole extended gag about Rock Hudson being gay. Which I’m sure was funny in 1959, but is even funnier in 2023.

Tony Randall, as he often does, appears as Hudson’s best friend who complains about how hard it is to be rich. ‘You started out with nothing and you’ve really made something out of yourself!’ he tells him, ‘Me, I started out in college with eight million dollars, and I’ve still got eight million dollars. I just can’t seem to get ahead.’ I’m really into Tony Randall now, by the way, that’s my new thing.”

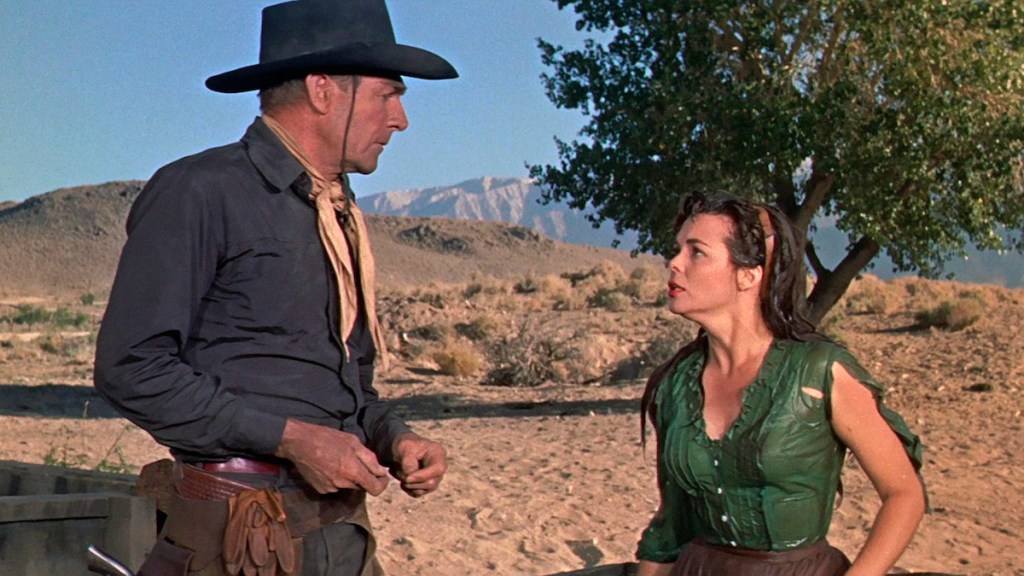

Comanche Station (1960)

Dean: “The last and best of the ‘Ranown cycle’ of westerns directed by Budd Boetticher and starring Randolph Scott, Comanche Station is a classic elegy for the aging gunfighter in a closing frontier, with never-better work from Boetticher, Scott and writer Burt Kennedy. Jefferson Cody (Scott) purchases the freedom of Nancy Lowe (Nancy Gates) from a Comanche war band who’ve taken her as a slave, unaware her husband has taken out a bounty for her safe return. On the way home, they run into a small gang of outlaws led by Cody’s former associate, Ben Lane, and are forced to work together to survive, despite Lane’s obvious intent to double cross them.

There are no true night scenes in the film, just glorious sunlit days and eerie day-for-night twilights that blur together into an uncanny waking nightmare. Every character feels vivid and fully realised, even as Kennedy pushes his already minimalist dialogue into the elliptical. I especially loved Lane’s dim-witted but good-hearted lackey, Dobie, whose moral struggle with the planned murder of Cody provides some of the film’s best drama. Between all the tense confrontations and sinister dialogue, Boetticher shoots transitional and establishing shots of the California landscape like he’s writing an ode. Now that’s cinema.”

The Comedy of Terrors (1963)

Dean: “In the midst of producing his acclaimed series of Edgar Allan Poe adaptations, Roger Corman hired Richard Matheson – one of the three writing geniuses behind The Twilight Zone – and Jacques Tourneur – director of horror classics like Cat People – to take the piss out of them. It’s the only film to star all four of the legendary horror actors who worked with Corman in the sixties – Vincent Price, Peter Lorre, Basil Rathbone and Boris Karloff – and it just might be the most perfect horror comedy ever made.

Price and Lorre take the lead roles of dastardly alcoholic undertaker Waldo Trumbull and his lockpicking fugitive assistant Felix, who defraud grieving customers by reusing the funeral home’s single coffin over and over. The film is both an excellent farce in its own right, dense with gags from start to finish, and a wonderful riff on the tropes and conventions of Poe, especially the deathlike paralysis of cataplexy, one of two ailments suffered by Rathbone’s cantankerous landlord. (The other is performing Shakespeare in his sleep.) Poe is a very funny writer, but he’s never written anything as funny as the buried alive scene in The Comedy of Terrors, which also features a delightful cameo from Joe E. Brown.”

Cruising (1980)

Ciara: “Even before Cruising was released, gay rights protestors were plaguing production, believing that the film was homophobic. At the same time, the MPAA demanded forty minutes – mostly of gay sex – be cut for it to be given an R rating. (William Friedkin says United Artists destroyed the cut footage.) Al Pacino plays Steve Burns, a cop who goes undercover in the gay leather scene to find a serial killer targeting gay men. The police captain (Paul Sorvino) says it’s because he’s a similar body type and colouring to the men killed. But you wonder if the captain sees something else in him that’s similar to the victims.

Watching Cruising in 2023, it didn’t seem homophobic in the slightest. It is, for one, profoundly homoerotic: we’re seeing these sex acts through Steve’s eyes, and the heart of the conflict in his character is that he finds it erotic. More importantly, the film makes clear that the leather scene is a pretty small slice of gay life, even for the men in it: Ted the aspiring playwright in a steady, monogamous relationship with Gregory; Skip the waiter who is vaguely baffled by the mildest of kink; the PhD student grieving and refusing to grieve his father; sex workers coerced into giving police officers’ oral sex. This variety of sympathetic gay characters is sharply contrasted with the monolithic, malevolent way the cops view LGBT people: as, if not monsters, than close to it.

Ted says when they find the killer they’ll put him on the vice squad. Maybe he’s already on it.”

Popeye (1980)

Dean: “I decided to watch this film before I went to see Barbie after hearing many comparisons of the two films by critics. Very early on, I was so smitten with it, I started to ask myself if this was the greatest film Robert Altman ever made. But then, as it went on, my feelings slowly began to change, until I started to ask myself if this was the greatest film anyone ever made. There is a special kind of wonder in films that manage the impossible alchemy of not just translating, but transmuting cartoon logic and visuals to live action, and Popeye might be the best to ever do it. Better than The Mask, and maybe even better than Speed Racer.

But above and beyond all its other virtues, nothing in this film – or most others – is as transcendent as Robin Williams as Popeye and Shelley Duvall as Olive Oyl. Each gives one of the best performances ever captured on screen – Duvall was put on this Earth to play Olive – but together their chemistry is nothing short of miraculous. I get choked up any time I think about their love duet, ‘Sailin’’, and I think about it a lot. Masterpiece feels like too small a word.”

Sleepaway Camp (1983)

Ciara: “I can’t tell you how Sleepaway Camp ends, but Sleepaway Camp is defined by how it ends. It reframes everything: a ‘What the hell? Of course!’ of the best twists. It is the most subversive and radical film of its kind even as it forces the audience to live with ambiguity. Maybe the ambiguity is the most radical thing about it. It is empathetically not the ambiguity of unwillingness to make a statement. That shot – you know the one – might be the best one in cinema, and it’s one hell of a statement.

But let’s put that aside. Even if it didn’t have that ending, Sleepaway Camp had already established itself as one of the greatest slasher movies ever made. Its balance of John Hughes-ian teenage-realist dialogue and gruesome, well-choreographed kills is what slasher movies were made for. It somehow has room for awkward, lovely, tentative romance and an upsettingly real depiction of teen-girl bullying. It is a movie in which, like Allison says in The Breakfast Club, when you grow up, your heart dies: the adults at the camp are so willing not to give a shit when it’s the path of least resistance, and when the adults are in charge, the path of least resistance is to not protect the kids – whether they’re showing up dead or whether workers are molesting them. The ending reframes everything, but it doesn’t reframe any of that.”

Metropolitan (1990)

Ciara: “’You know the French film, The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie?’ Charlie (Taylor Nichols) asks during one of his political-philosophical spiels, ‘When I first heard that title I thought, finally, someone’s gonna tell the truth about the bourgeoisie.’ What a disappointment.’ Metropolitan is a movie about the discreet charm of the bourgeoisie. Its characters are so posh that they seem unstuck in time, living nineteenth-century social lives in the 1990s: the last days of a civilisation gone with the wind.

The Sally Fowler Rat Pack spend Christmas and New Year’s going to debutante balls and having bullshit conversations about politics and literature. There’s Nick (Christopher Eigeman), whose sparkling wit should make him a talk show fixture. Audrey (Carolyn Farina), whose favourite Jane Austen is Mansfield Park. Charlie, whose in love with her, when he’s not busy defending the class interests of the untitled aristocracy. Fred, whose passed out drunk most of the movie. Our way in is the merely upper-middle-class Tom Townsend (Edward Clements, who surely deserves a Wikipedia page, you scoundrels): a committed socialist, but a Fourierist, not a Marxist, who meets these people after going to one of these things one time on a whim. Audrey, of course, falls in love with him.

Metropolitan reminded at once of John Hughes teen movies and War and Peace, set amongst people at the wrong age and in the wrong time to star in either. Things that threaten dramatic stakes – Tom’s class impostery, or the Charlie/Audrey/Tom love triangle – do nothing to disrupt the purity of its hangout movie vibe. Right until the Rat Pack is down to the rats.”

Ghostwatch (1992)

Dean: “On Halloween Night, 1992, the BBC broadcast Ghostwatch for the first and, so far, only time. Presented as special live coverage of an allegedly haunted council house in London, it featured the face of the BBC, Michael Parkinson, as its host, with Sarah Greene and Craig Charles reporting on the ground, and Greene’s husband Michael Smith overseeing calls from the public. Drawing on elements of the legendary Enfield haunting, a single mother and her two daughters have been tormented by a sinister poltergeist they call ‘Mr. Pipes’, and the BBC are here to either prove or debunk the existence of the paranormal, with Greene and her crew staying in the house for the night.

If it’s not quite found footage, it’s still the only film I’ve ever seen to compete with The Blair Witch Project for bloodcurdling verisimilitude. All the presenters do an absolutely incredible job of selling the events as real, and I especially enjoyed how late into the night Craig Charles is still cracking jokes about how he thinks ghosts are nonsense, unaware of how poorly Greene’s evening is going mere yards away. I don’t want to give away too much, but suffice it to say, any lovers of horror who leave Ghostwatch out of their lives are missing out on something truly special.”

Gladiator (2000)

Ciara: “You guys hear about this movie Gladiator? Revisionist historical epic as sports movie. A general who becomes a slave who becomes a gladiator who becomes an icon of hope, who dies to restore the Roman Republic. He’s the hero in a Shakespeare history play, and he’s Stone Cold Steve Austin fighting Vince McMahon. He’s Maximus, and he’s played by Russell Crowe, and I love him.

His villainous foil is Commodus, played by Joaquin Phoenix as young as I’ve ever seen him. Phoenix arrives fully formed: creepy, clawing, at once sinister and feeble. His Commodus is snivelling, pathetic, hungry for power that he imagines will fill the holes inside him where his father – Marcus Aurelius (Richard Harris), the emperor – wouldn’t, or couldn’t. Or hungry for the next best thing, fucking his sister.

It’s about wrestling, it’s about dancing, it’s about sport. Being a great fighter doesn’t make you a great gladiator. A great gladiator knows how to play to the crowd, how to put on a show. Oliver Reed is the trainer who used to be a gladiator, and this is what he has to teach. Through Maximus, he rediscovers his love for gladiatoring as something that means more to him than just cash, like Paul Newman in The Colour of Money. If a great gladiator can get the crowd to root for mercy, maybe he can save Rome. Save it from itself.

Rome in Gladiator has an obvious analogous relationship to the US. The shining city on the hill. An empire that was founded as a republic, sunk into corruption and violence and horror. It feels like a pointed post-9/11 allegory, even as the calendar insists that’s not the case. Or maybe it’s a story about how it’s been this way before, over and over and over again.”

The Lord of the Rings (2001-03)

Ciara: “It turns out, long after he was the splatter comedy king of the southern hemisphere, but before he became a documentary filmmaker/professional Beatles fan, Peter Jackson adapted The Lord of the Rings. Apparently it was a pretty big deal.

I don’t need to tell you about the Lord of the Rings movies, because you’ve seen them. Everyone’s seen them. I think every film critic or cinephile of my generation tells the same story of learning to love film in no small part by watching the behind the scenes featurettes on Lord of the Rings DVDs. I don’t have a particularly good excuse for why I hadn’t seen them. I don’t even have a bad excuse.

But, dear reader, the rumours were true. The Lord of the Rings movies rule. They are majestic in scale in a way perhaps only possible in that brief window where CGI made impossible dreams real without becoming the flatly-lit all-over sludge it is too often today. They feel like Peter Jackson movies, my Peter Jackson, the guy who made Braindead, who I found it vaguely incomprehensible made the Lord of the Rings, right up until I saw it. And it deftly handles its huge ensemble, never sacrificing psychological richness even as it maintains such an epic scale. It is, when you get down to it, a story about a good man dogged with temptation. I would die for Sam and Frodo, probably.

And Bilbo asking at the end if Frodo ever saw that ring he used to have? Art.”

Universal Soldier: Day of Reckoning (2012)

Dean: “I didn’t care for the original Universal Soldier all that much, but I heard the direct-to-video sequels by John Hyams, son of the first film’s cinematographer, were great a long time ago, so I finally gave them a whack this year. The first, Universal Soldier: Regeneration, is a great little action-horror film with more than a little Predator in its DNA. But Day of Reckoning is something else altogether. I rolled my eyes when I saw people have compared it to the works of David Lynch, but by the end, I was like, yeah, fair enough, this, again, direct-to-video Universal Soldier sequel is Lynchian as fuck. It was also instantly one of my favourite movies ever.

This is a film where the main character doesn’t notice he’s been superhuman this entire time until over an hour in, and all the better for it. This is a film where a po-faced Jean-Claude Van Damme gets visibly Jokerfied by blood splashing over his mouth in a rictus grin. A disturbing, haunting vision of a masculinist terrorist uprising against the fascist military-industrial state that created them to serve as black ops supersoldiers, as bleak and brutal an action-horror film as ever existed. And it’s a direct-to-video Universal Soldier sequel.”

The Wolf House (2018)

Dean: “Colonia Dignidad was an isolated religious commune of German immigrants established in Chile in 1961 by a Nazi child molester who governed it as a fascist cult leader for over three decades. If that completely true sentence already seems dense with horrifying details, consider it also doubled as a concentration camp for victims of the Pinochet dictatorship for over ten years, where dissidents were tortured, raped and murdered by state security forces. The Wolf House presents itself as a film made by and for residents of Colonia Dignidad, a stop-motion fable that evokes the classic Soviet fairy tale cartoons of Soyuzmultfilm, the surreal claymation of Jan Švankmajer and the oppressive psychological atmosphere of 1984. The result is an astonishing collage of mixed media and methods, a film so eerie it made me queasy.

It should go without saying The Wolf House doesn’t play its premise straight, but one of the most fascinating things about it is how it subverts it in ways that echo the defiance of animators operating under the umbrella of Soviet censorship. The plausible deniability of fairy tale and allegory, the use of visual composition to speak the unspeakable. I’m also just a huge fan of paint-on-glass animation and there’s a bit where the main character throws a ball that just knocked my socks off.”

Wrath of Man (2021)

Ciara: “Let me tell you a secret. Two years ago, one of the greatest films of all time was released. You’ve never heard of it, and not because it’s some obscure indie movie from Eastern Europe. In fact, it starred the only true contender to Tom Cruise’s title of the last movie star: Jason Statham, the son of a dancer and a street seller. It was directed by Guy Ritchie, the only director on earth with the good sense to look at Jason Statham and go “this motherfucker can act.” I’m not even sure Guy Ritchie knows that Statham can do high kicks or whatever.

Instead, Statham has the quiet menace of Alain Delon at his coolest (in both senses of the word). The tight-lipped power and presence of Clint Eastwood at his most vengeful. The qualifying score for the shooting test is 70, and he gets 70: and you know, deep in your bones, that he didn’t just scrape qualifying, he’s so good he got the qualifying score precisely. Wrath of Man – I know, awful title – is a heist movie with a non-linear structure, but there’s nothing Reservoir Dogs here, even as Ritchie is perhaps the Tarantino rip-off-er par excellence. Instead, the non-linearity is elegantly used to reveal that the heist movie we thought we were watching is inside a bigger, tenser, more moving revenge movie. There’s nothing of the blokey, jokey, quick cuts, snappy voiceover vibe of Ritchie and Statham’s earliest collaborations. It’s steady, clear-eyed, serious. Substantial. But still fizzes with fun when the moment comes.

Also, Post Malone shows up for two seconds and gets shot in the head. Five stars.”