Dennis Reynolds is a bad man. All the characters on It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia are awful people – it’s kind of the premise of the show – but Dennis still stands apart. Like the rest of the Gang, he’s all narcissism, bigotry, and rage, ready to explode at any moment at anyone he perceives to have crossed him. Once, when a guy called him a narc, Dennis’s revenge was getting the guy to chain himself to a tree overnight during a storm while Dennis slept with his girlfriend, and that’s pretty mild when you’re grading on the Dennis curve of bad behaviour. He’s a prolific rapist, and he might be a serial killer.

He’s also one of the best characters in the history of TV.

Dennis is that rarest of things, a satire that is also a rich, psychologically complex character, and doesn’t stop being one to be the other. In an era where “satire” gets used and abused to justify, like, anything that has the faintest glimmer of irony to it, Always Sunny is a truly great satire, uninterested in being subtle or ambiguous. Dennis Reynolds is rape culture: “the implication” might be the best rape joke yet written, masterfully deconstructing the twisted mindset of the rapist who doesn’t think he’s a rapist. He’s pick-up artistry: his D.E.N.N.I.S. system (Demonstrate value, Engage physically, Nurture dependence, Neglect emotionally, Separate entirely) for getting women is a parody of the F.M.A.C. system (Find, Meet, Attract, Close) from Neil Strauss’s The Game. He’s a go-getter who just won’t take no for an answer: “I’m a winner… and winners, we don’t listen to words like no or don’t or stop.” Dennis is the ultimate nightmare version of liberalism, the kind of guy who says that of course black lives matter, but also, all lives matter.

But to the extent that Dennis is the embodiment of all those things, it is because he is the product of those things. Dennis is the offspring of where masculinity and capitalism meet abuse and untreated mental illness. He is a man who wants to be what men should be, and is broken by it.

One of my favourite things about television – and this goes especially for traditional episode-a-week television – is how it is both short and long. It comes in the shape of an hour or half-hour, but it becomes a standing fixture in your life in a way that non-serialised art doesn’t. You watch a film in two hours; you watch a TV show for years. You can grow up with it, and out of it, and shed a tear as it comes to an end, thinking of all you’ve been through with the warm, steady presence of this show by your side. The simultaneous short-and-long-ness of TV allows it to do a lot of neat things, many of which the “it’s like a ten-hour movie” crowd would be wise to consider, but it’s especially good for characters. You get to know them, a slow drip-drip of all the tiny things that make them tick, because you have a standing appointment to hang out with them every week. There are lots of TV shows that don’t take advantage of this – populated by characters that start out as, or quickly become, more archetypes than anything – but it’s something even highly episodic television has the capacity for, just because of how it’s built. Nothing on Star Trek: The Original Series will ever have long-lasting consequences, but that doesn’t mean the episode where we learn that Captain Kirk survived a genocide as a teenager doesn’t colour how I look at him in every episode that follows.

It’s Always Sunny started thirteen years ago, and I’ve been watching it for five. It’s both one of the most thoroughly episodic shows on air and one that, in its later seasons, demands close, engaged watching and a long memory to really appreciate. This structure is set out like a mission statement in season eight’s ‘The Gang Recycles Their Trash’, which consists entirely of recreations of and metacommentary on jokes from the previous seven seasons. It is, episode-by-episode, a show without sentimental moments or emotional epiphanies; the peak of Larry David’s “no hugging, no learning” mantra. But the slow and steady thirteen years of half-hour instalments has made it something moving, that gets to me right in the heart. It’s a drip-drip-drip of empathy.

Which is why when, in the twelfth season, Always Sunny suddenly grew emotional moments and character realisations, it didn’t feel hollow or cheap or even just out of place. It felt right, because the show had spent so many years setting that stuff up. Mac finally came out, and it was small and simple – Rob McElhenney’s brilliant smile and a barely-there piano – and it was, somehow, lovely in a show that I did not think capable of loveliness. It warmed my heart more than a thousand more sentimental moments in other shows. It felt earned, because Sunny had spent a decade earning it.

It’s Always Sunny had long been a show about refusing to face things, about characters that survive on their delusions. There are dozens of examples I could point to, but Dennis summarises it nicely in season ten’s ‘The Gang Group Dates’:

You can’t derive your self-worth from the opinions of others. No! No, [to Mac] you get your self-worth from when you convince yourself that you’re tough and that you’re straight…

[To Charlie] Or that you have got a shot with a woman who we’ve all banged, but who hates you…

[To Frank] Or you, that your penis could ever possibly remain erect for more than a couple of seconds – even with a cock ring on.

[To Dee] Or that you are a powerful woman instead of a dirty, dirty whore who bangs toad people…

Your true power comes not from outside sources but from the delusional stories that you all convince yourselves of. And no one, no one can take that away from you.

(When the Gang asks what about him, Dennis says that he’s “doing great.” That is Dennis’s delusional story.)

But in the twelfth season, it became a show about finally facing things. On the show where nothing really changes – whose characters are trapped in an endless cycle – everything changed. Mac came out. Charlie slept with the Waitress. And Dennis left Philadelphia to go be a dad.

There’s an episode a few years earlier where the Gang realise what has been obvious to the audience for years, that they’re alcoholics: they stop drinking for a couple of hours and all come down with a terrible “flu” that disappears when they start drinking again. Charlie asks what they should do with this information, and Dennis says to “stuff it deep down inside.”

“I’m a young guy!” Dennis says, passing along the cleaning bottle filled with booze.

“We’re just kids having fun, right?” Mac says. The question’s rhetorical, but not in the way Mac means it to be. They’re not kids, not anymore, not by a long shot.

In season 12, the Gang – other than Frank (Danny DeVito) – are in their forties. They’re not kids anymore, and Dennis is starting to realise it. The Gang go to a water park, and he bonds with a little girl, teaching her how to steal, and I kept waiting for him to do something really, really awful – but his downfall ends up being a sincere paternal instinct towards her.

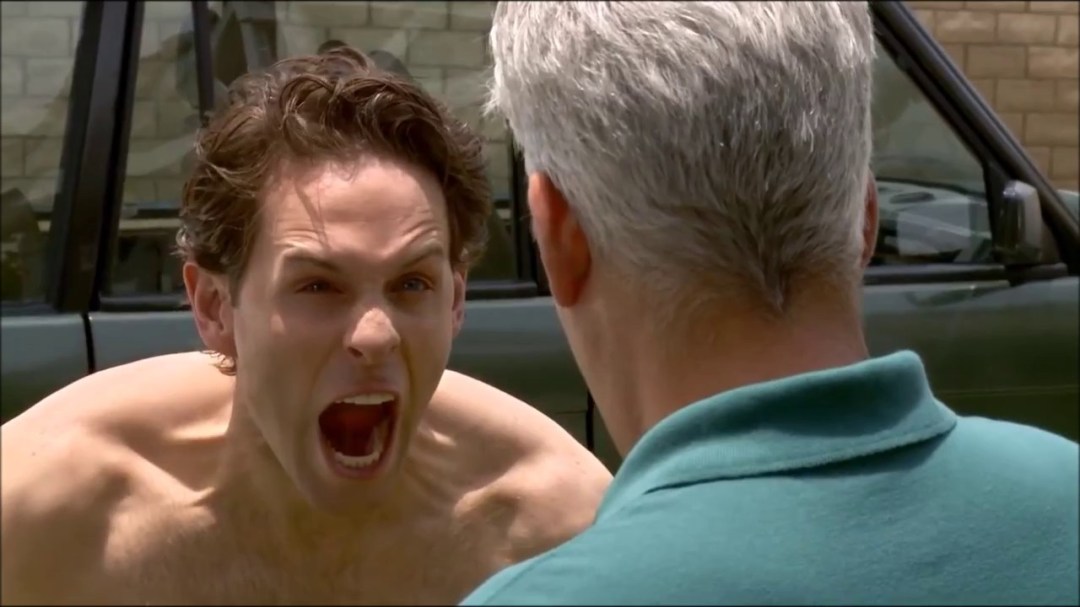

In ‘The Gang Tends Bar’, it’s Valentine’s Day, and Dennis wants everyone to do their jobs instead of their usual scheming, so of course they spend most of their time trying to figure out what his angle is. Mac and Dee both decide that Dennis must hate Valentine’s Day because he (by his admission) doesn’t have feelings, and they extrapolate nonsense from there. At the end of the episode, Dennis screams at them, and Dee, Frank and Charlie speculate that it must be about something else underneath: “We have feelings, and you don’t, and that’s why you hate Valentine’s Day!”

“Stop! Goddammit! I hate Valentine’s Day because you assholes never got me anything!” Dennis shouts, his voice close to breaking, shot through with more sadness than rage for once. Dee, Frank and Charlie stare in him in shocked silence. “Okay, and I have feelings. Of course I have feelings! I have big feelings, okay? A-and it hurts.”

It’s one of my favourite pieces of acting on the show, and maybe ever. It breaks my heart. And it works because we always knew Dennis’s claim not to have feelings was a lie: it’s true sometimes, but just as often, he feels too much. He has big feelings, and it hurts.

Then Mac comes in with a crate. Inside is a rocket launcher – a Valentine’s present for Dennis, ordered off the dark web – and Dennis is choked up and close to tears opening it. It’s not some over-the-top display, proof of his big feelings: his voice is quiet, his words are short, his face is contorted in a bad facsimile of a neutral expression. Dennis asks how Mac knew he wanted it, and Mac says, “Because I know you, man. Also, you casually mention RPGs like a weird amount.”

The rocket is missing, so Dennis can’t shoot it, and Mac is profuse with apologies. Dennis has had red-faced, veins-protruding rage meltdowns over a lot less, but not this time: “Mac, I don’t care. I love it. You figured out the one thing I wanted more than anything else in the entire world and you got it for me. And it’s perfect.” There’s one of the show’s handful of soft, emotive musical cues.

The Gang are awful people, but they do love one another, in a way that’s strangely innocent and disarming. There was when they tried to recreate Charlie’s dream book for his birthday, even as they had no idea when his birthday was. There’s the sweetness of Charlie playing Nightcrawlers with Frank when he’s so disorientated and scared in ‘Being Frank’. There’s Mac and Charlie’s tradition of throwing rocks at trains every Christmas. They love each other like children – I suppose because they never learned how to love people any other way. They’re all they’ve got, and always have been.

Mac buys Dennis the rocket launcher, and it’s the perfect expression of the Gang’s love. They understand him – because I know you, man – but it’s the worst parts of him, his darkest histories and his most destructive impulses. They could never want for him to be a better man.

Throughout the show, Dennis chases after an ideal he wants to embody. He starves himself to maintain a “perfect” body. He rapes women and convinces himself that it’s consensual because he believes a man’s worth is determined by his sexual prowess. He’s a winner, and winners don’t listen to words like no. He convinces himself that he’s still seen as upper-class. That he’s beloved and well-respected and God-like.

“We [as a society] celebrate money and we celebrate people with massive egos. Dennis is Donald Trump having failed. Donald Trump is Donald Trump having succeeded,” Glenn Howerton said in an interview with GQ, “…he was taught the same fucking things we are. In a way, you almost can’t blame him. He happens to be the most grotesque version of it.”

The Gang are so insular and co-dependent that it’s hard to imagine how any of them could survive outside of the small, strange world they’ve built for themselves. Dennis tries to assert dominance within it – ordering for the rest of the Gang when you go out to eat – because out in the real world, he’s a pathetic lowlife, just like the rest of the Gang, a scumbag and a loser. And it’s not that the real world is wrong about him, even. But his self-evident authority is the delusional story Dennis tells himself to derive his self-worth, and confronting it is incredibly painful.

And so Dennis, getting older and wanting for some vague amorphous more than this, finds himself trapped.

“Men feel the contours of a box, too, but they are told that box is of their own manufacture, designed to their specifications,” Susan Faludi writes in Stiffed, her book about post-war American masculinity, “Who are they to complain? The box is there to showcase the man, not confine him. After all, didn’t he build it – and can’t he destroy it if he pleases, if he is a man? For men to say they feel boxed in is regarded not as laudable political protest but as childish and indecent whining. How dare the kings complain about their castles?”

Dennis has always been trapped, but he realises it much too late. He’s defined himself against an impossible and destructive ideal, and retreated into delusion to cope with his inability to live up to it. I can almost hear him saying, “The box is there to showcase the man, not confine him.” It’s only when he’s given the glimpse of another kind of life that he reckons with how confined he is in his current one.

On a layover in North Dakota in season ten, Dennis got a woman named Mandy pregnant. In the finale of season 12, she comes to Philadelphia with his son, Brian Jr. – named after the assumed identity Dennis was using – and most of the episode consists of various schemes to get rid of her: Mac wants to pretend to be Dennis’s lover, and Frank wants to pay her 5,000 dollars to sleep with him (he thinks that what made the proposal in Indecent Proposal indecent was that it was too much money). They do get rid of her, just by being so bizarre that she decides to leave, and so the Gang go back to the bar to celebrate.

Everyone else is dancing when Dennis, sitting on a stool with a beer in his hand next to his rocket launcher, says, “I can’t do this.” It’s flat, and he becomes more animated as he continues, as if he’s suddenly aware of his surroundings: “This is crazy. What are we doing? I can’t… I – I can’t do any of this shit anymore.”

He stands up, and the music cuts out, and the rest of the Gang ask him what he’s talking about.

“I’m leaving. I’m gonna go be a dad.”

The Gang protests: Dee says he can’t just leave, Frank says Dennis doesn’t know the first thing about being a dad.

“Well, you know what, Frank, I’ll figure it out, okay?” Dennis says, “Because I don’t want my kid to grow up like I did, with some asshole dad who was never even around.”

(“You talking about me or Bruce?” Frank asks, like salt in the wound.)

The tragedy of it is that we know Dennis will fail. For once, he’s chasing being good instead of grotesquely perfect. He doesn’t want his kid to grow up like he did, because he grew into this fragile, fucked-up man who hurts everyone he touches. But that’s who Dennis is, and it would take so much for him to start to fix himself, none of which he has: years worth of therapy, rehab and treatment for his borderline personality disorder being top of the list. Dennis realised he was trapped, but he thinks he can destroy the box if he pleases.

2 thoughts on “A Mid-Life Crisis in North Dakota”