Save the Tiger is the story of Harry Stoner, the owner of a clothing manufacturer in Los Angeles, as he tries to keep his company afloat through a season of hardship. He goes to numerous ethically dubious lengths to do so, and worst of all, he spends the whole time pining for the simplicity of his youth, when baseball players would put the spikes of their cleats right in your face and you knew how a plane stayed in the air because you could see the propeller on the wing. Even Jack Lemmon, the most charming man in history, can’t make Harry Stoner’s meandering trips down memory lane anything but annoying.

Then Harry stands at a podium to shill for his company’s new fashion line. He looks out on the crowd and his face turns white. His audience of middle-class drunks have been replaced by a legion of war dead, young men that Harry saw blown to pieces and shot to stillness in the Second World War. They stare at him in total silence. Harry tries to speak, but he can’t.

This is what we talk about when we talk about nostalgia.

Nostalgia has always been a political and cultural football, even before we had a name for it, but it’s become a meaningless buzzword on the Internet. Or worse, it’s become a word overstuffed with so many possible meanings that it’s impossible to talk about with any kind of clarity, because everyone is just projecting whatever they want on to it. Nostalgia is a universal feeling, so we rarely stop to think about what nostalgia is before we make declarations about what it means. But, at the same time as we all engage in nostalgia, we also engage in the ritual public shaming of the nostalgia of specific individuals or groups. Sometimes that shame is warranted, of course, but more often, I suspect, we’re simply accusing other people of lacking our own nuanced or self-aware approach to nostalgia on the basis that we can’t experience their thoughts and feelings, and therefore have no evidence that they’re as wise or reflective about their nostalgia as us.

Of course, on the same basis, we could just as easily conclude that we’re the only conscious beings in existence and all other people are mindless zombies who just seem conscious. But we tend not to do that, and we should tend to not assume other people’s thoughts and feelings are less complex than our own. The law of averages suggests that everyone’s nostalgia is about as shallow or deep as the next person’s, and the fact that so many people who write thinkpieces about nostalgia make uncritical assumptions contrary to that fact about the nostalgic feelings of other people suggests that people who write thinkpieces about nostalgia have an inaccurate and unjustified perception of their own aptitude for critical thinking.

As a person writing a thinkpiece about nostalgia, I’ll try to bear that in mind.

Part 1 – What Is Nostalgia?

The term “nostalgia” originated in the seventeenth century as a medical term for the extreme homesickness experienced by soldiers, derived from the Greek words nostos (“homecoming”) and algos (“pain”). The history of nostalgia’s journey from a medical condition to a universal feeling is long and complicated, but this article by Melissa Dahl in New York gives a decent overview, noting that as late as the US Civil War, soldiers received medical leave to treat it. Nostalgia was also an epidemic on slave ships, driving many slaves to suicide, as Ramesh Mallipeddi discusses in an excellent but sadly paywalled academic essay titled “‘A Fixed Melancholy’: Migration, Memory, and the Middle Passage”.

There is an interesting juxtaposition between Mallipeddi’s account, which convincingly reads broader terms like “melancholy” as stand-ins for what would otherwise have been termed nostalgia, and Dahl’s, which says “we would likely call what happened to [the first person diagnosed with nostalgia] an acute case of anxiety or depression” nowadays. Extreme homesickness is no longer treated as a distinct medical condition (though Dahl notes that it’s received some attention as a contributor to mental health problems in immigrant communities), but there’s a sense from both accounts that that’s less because it was never a medically unuseful term and more that contemporary psychiatry has dissolved its specificity among a number of broader diagnoses. Many researchers now believe that high rates of mental health problems in certain ethnic populations that have experienced historic atrocities (e.g. Native Americans) are attributable not only to the their present conditions, where they often continue to face racial discrimination and violence, but to cultural trauma that continues to affect even those born long after the atrocities occurred. Extreme homesickness may yet see a similar resurgence as a subject of medical concern.

The medical history of the term “nostalgia” remains relevant to the discussion of the emotion we now call nostalgia because it illuminates a key idea: nostalgia is an emotion that arises from a sense of dislocation. Psychological studies such as those described in Current Direction in Psychological Science show that we become more nostalgic in response to negative feelings like loneliness or sadness, even sadness that’s not our own. The prevalence of nostalgia in the general population is known to increase during times of social and economic upheaval, as the society we knew (or thought we knew) disappears from under our feet, or on a more personal level, as people are ejected from their familiar place in society, by unemployment, by new poverty or by the migration, both internal and international, that tends to follow convulsive economic shifts.

This might explain the tendency of much political writing to attribute nostalgia to a base regressive instinct in those who formerly held more privilege in society (e.g. white Christians in the United States) to return to their more privileged past (e.g. before the passage of the Civil Rights Act). But one of the most striking findings in the studies I referenced is that though nostalgic memories were more likely to cause a combination of both happiness and sadness than memories of ordinary events or even purely positive events, nostalgic memories also featured “more frequent expressions of happiness than of sadness and induced higher levels of happiness than of sadness”. We talk about nostalgia like it’s a purely rose-tinted retrospection on a past that never existed and assume that it drives regressive politics like Making American Great Again, but nostalgia is a more complex and nuanced experience, and it actually helps us to cope with the difficult present rather than reject it through what these studies call “redemption narratives”. We’re especially nostalgic for good times that followed bad times and the memory that good times followed bad times before helps us believe that good times will follow bad times now.

While nostalgia is often described as if it has a particularly thorny relationship with historical truth, the fact is that all of our memories are of a past that never existed. Our memories are inherently unreliable lo-fi copies of sense impressions infused with specific emotional perspectives – in fact, some theories suggest that many of our memories may be memories of memories. We might think we remember a day at the beach when it’s actually a memory of a previous occasion on which we remembered it, as if we took a photo of a painting, then cut the painting out of the photo and treated it like the original. We have an unjustifiably greater sense of doubt towards memories we associate with strongly positive or negative emotions – nostalgic or traumatic memories – even though lots of people thought Nelson Mandela was dead for decades before he died without any obvious emotional explanation to pin it on.

In other words, though nostalgia is typically defined as a sentimental yearning for the past, the reality is a lot more complicated. Many of us experience nostalgia about places and objects from times we’d never wish back. People who had abusive childhoods full of pain and misery still have nostalgic feelings for parts of their past. We are capable of a specificity to our nostalgia – we can be nostalgic for a good moment without being nostalgic for the bad day around it, and we can be nostalgic for the art or the food or the fashion of a time period without being nostalgic for whatever wars or atrocities or systems of oppression coexisted with them. Nor is nostalgia itself a desire to return to the past, though the two feelings can intermingle. More commonly, it is an emotional response to the miserable conditions of our present that actually improves our ability to deal with them.

Importantly, because this is still a pop culture blog, nostalgia is not the same as liking things from the past. My dad’s love of Thin Lizzy didn’t turn into nostalgia at some point between the first time he heard “Jailbreak” and the present moment. He just likes Thin Lizzy. This seems like an obvious point, but how many confused, handwringing articles about why we’re still “obsessed” with art from the eighties have ever taken seriously the possibility that people might have just made a lot of good art in the eighties? I love Thin Lizzy and I wasn’t even born until almost a decade after Phil Lynott died. Similarly, I will go to my cold, cold grave listening to My Chemical Romance, and it won’t be out of nostalgia, it’ll be because they’re the greatest band in the goddamn world.

Part 2 – “Times Have Not Become More Violent. They Have Just Become More Televised.”

As noted in this introduction to the Iowa Journal of Cultural Studies’ nostalgia issue, there is a deeply ironic tendency among those who criticise nostalgia to engage in nostalgia: “back in my day, we didn’t pine ruefully for the past!” I don’t want to be one of those idiots, so let’s consider in what ways and for what reasons nostalgia has changed in recent times, not just as a feeling, but as a social phenomenon. People have always been nostalgic, but they haven’t consistently practiced nostalgia in the same ways throughout history.

Just as many Americans incorrectly believe crime is on the rise when it’s been decreasing for around twenty-five years in part because violent crime receives a disproportionate amount of coverage in the news, so our sense that we live in a more nostalgic time is shaped in part by the perceptions we develop from our interaction with media. We can see a similar effect in the notion that 2016 was a particularly lethal year for celebrities, when it was actually either average or possibly a bit less lethal than most years. But, as this article in the Huffington Post outlines, people who became celebrities in the pop culture boom that followed the 70s are getting older, more and more people can acquire some level of celebrity as the pop cultural zeitgeist becomes ever more fragmented into niche interests and audiences, and perhaps most importantly, social media has changed the speed at which we learn of celebrity deaths, the number of celebrity deaths we learn about and repeatedly exposes us to public grieving for celebrities, all of which combined to make 2016 seem more deadly for the famous than it was.

The pop culture boom is not irrelevant to the question of why the present moment seems more nostalgic – there is more pop culture to be nostalgic about than any other time in history – but social media is the more important factor. Previously private displays of nostalgia have now been moved into a public or at least semi-public venue. Before social media, the main way I experienced the nostalgia of others was my mam saying “they don’t make music like this anymore” when our local radio station played a Culture Club song or something. Now, the main way I experience the nostalgia of others is scrolling through the baffling hell of my Facebook feed until nonsense like this shows up because someone else liked, shared or commented on it:

Memes like this are among the primary forms of nostalgia in the online age, and represent not just the transformation of the private into the public, but the ability of social media to connect the otherwise geographically separated fans of any item of pop culture, no matter how niche. Social media allows them to engage in all the rituals of fandom, including nostalgia, that would otherwise be impossible, or at least substantially more difficult, because they probably don’t personally know a lot of people in their daily lives who love Too Close for Comfort. Our age may or may not be more nostalgic, but if it seems more nostalgic, it’s at least in part because we have more avenues to express our nostalgia than ever before, and we take full advantage of them. Maybe people were just as nostalgic in the past, but either kept it more bottled up inside or created Happy Days.

These memes also represent the commodification of nostalgia. They’re just one small outlet of the sprawling nostalgia industry, using our clicks to make money by sneaking in ads for novelty t-shirts and mugs between the pictures of Power Rangers. But again, nostalgia is not the same as liking things from the past, and that distinction has confused a lot of analysis of the commodification of nostalgia, especially as regards Hollywood’s addiction to remakes and reboots. Lots of discussions of the staleness of Hollywood lump together remakes and reboots with sequels and spin-offs regardless of whether they’re blaming nostalgia or fan boys, even though a combination of dozens of cultural and economic dynamics drive all four in different ways at different times. Even if you ignore the fact that audiences aren’t monolithic and their motivations for seeing films can’t be easily generalised without extensive survey data that no one is collecting, it’s hard to explain whether a film based on an existing property is trafficking in nostalgia or not.

How far apart do sequels have to be for the sequel to be exploiting our nostalgia? John Wick: Chapter 2 wasn’t trying to make money from our nostalgic feelings for John Wick, a film that came out three years ago, but you could make a case that Finding Dory was doing exactly that with our nostalgic feelings for Finding Nemo. The Karate Kid (2010) was an obvious cash-in remake of the still-popular The Karate Kid (1984), but do we really think that Alfie (2004) was an attempt to profit from the public’s enduring love for Alfie (1966)?

When we skip past these questions, we confuse the very real issues in the film industry right now. We blame Transformers’ continued success as a franchise on nostalgia for toys and cartoons that we must know, if we thought about it for even a second, almost no one who goes to see Transformers movies even knew about before the first movie came out, by sheer virtue of the fact that Transformers: Dark of the Moon grossed over a billion dollars and there’s no way the pre-existing Transformers fandom was that big or that rich or could possibly have bought that many tickets even if it was. We blame “fan boys” who can’t get over a movie franchise from the eighties for the fact that Disney will make a Star Wars movie every year until the sun explodes, as if we really believe they have the power to direct the studios’ business strategy through the sheer power of their market demand. We ignore how the massive profit incentives of the giant corporations that own all the film studios now drive them to reuse safe intellectual properties they already own to simultaneously cut their bottom line and make movies that can perform well in international film markets, especially China, on the basis of their cultural cache rather than gamble on original ideas with a higher risk of flopping.

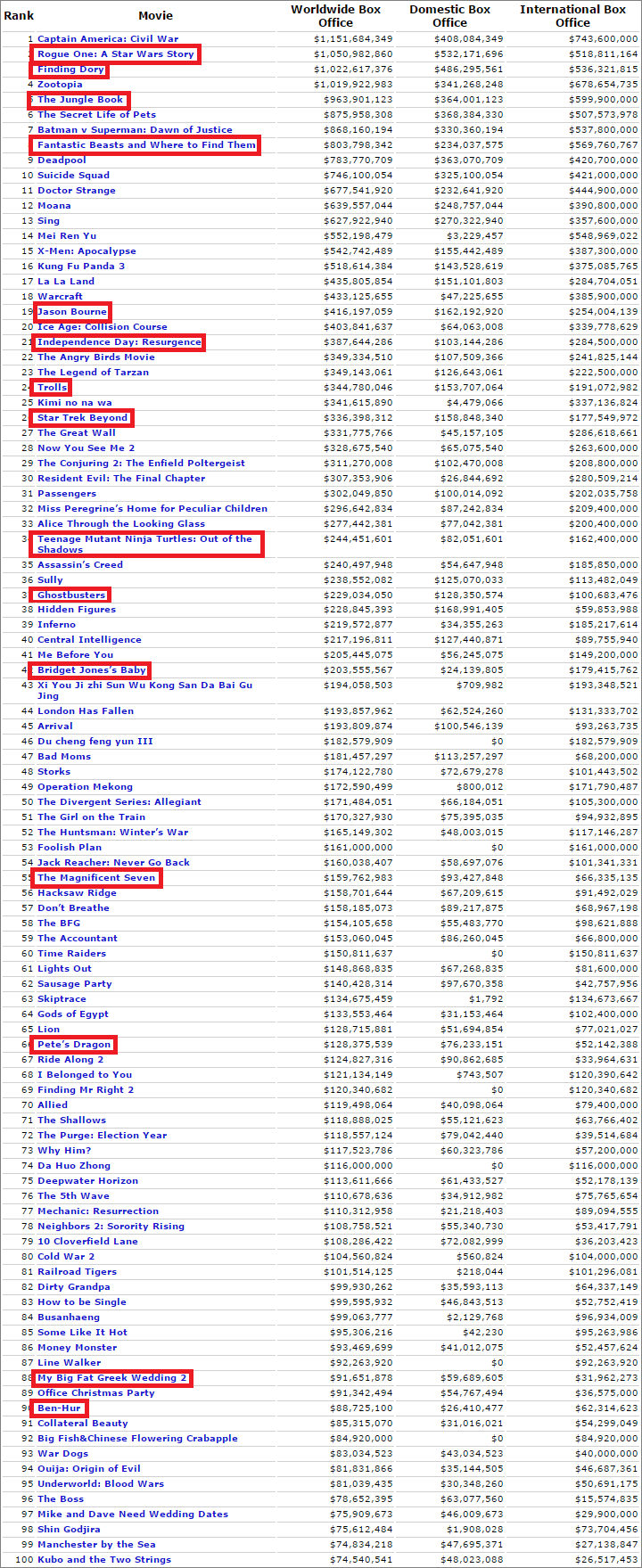

To illustrate the importance of teasing out these distinctions, let’s take a look at the box office figures for last year:

I’ve highlighted the films I think can fairly be said to be exploiting nostalgia to some extent, on the basis of what I’ve called the Alf Rule – films whose main reason for existing is the studio saying “Remember Alf? He’s back! In pog form!”

I’ve interpreted the rule fairly generously, including films like Ben-Hur (2016) and Finding Dory that arguably don’t trade on nostalgia, and even then only came up with 15 films out of 100, two of which, the remakes of Ben-Hur and Ghostbusters, were commercial flops. The list is saturated with sequels, spin-offs, animated films and superhero movies, but nostalgia doesn’t seem to sell as well as thousands of nostalgia thinkpieces would have us believe.

We can see similar results on television: for every successful show like Lethal Weapon or MacGyver, there’s a Minority Report or Limitless or The Muppets or Uncle Buck or Rush Hour or Heroes Reborn or Charlie’s Angels or Frequency, not to mention shows like Cruel Intentions or Beverly Hills Cop that never made it to air. If we look at the big picture instead of cherrypicking famous counterexamples, it looks less like we’ve been turned into nostalgia zombies enthralled to the dark magic of Hollywood and more like giant corporations are trying to shove nostalgia down our throats with mixed results.

Of course, there are more ways that movies and TV shows can trade in nostalgia than just remake and reboot old movies and TV shows. What about nostalgia for the styles and genres of eras past? What about movies that try to be how movies used to be? Yes, I’m afraid it’s time to reawaken the most bafflingly vicious cultural battle of the last year.

Let’s talk about La La Land.

Part 3 – “How Are You Gonna Be a Revolutionary If You’re Such a Traditionalist?”

We pivot now from the popular reception to the critical discourse. If you’re not the kind of person who reads a lot of pop culture writing on the Internet, you might be unaware that after the demand for contrived thinkpieces about Ghostbusters (2016) subsided, its place in the seasonal movie thinkpiece industry was foisted upon Damien Chazelle’s hit musical film La La Land. We at The Sundae are big fans of La La Land, but others have decried it as racist because it’s about two white people, one of whom likes jazz, trying to make it in the entertainment industry when it’s harder for non-white people, or as sexist because it contains a scene in which a man explains why he likes jazz to a woman.

I have no interest in relitigating the vast majority of these arguments, and especially little interest in those arguments that criticise aspects of La La Land that are only a problem when it’s aggregated with the rest of the film industry (e.g. the whiteness of its cast wouldn’t be so much at issue if film casts were generally more diverse) because such problems aren’t solved or even much relieved by having thirty-thousand entertainment journalists, bloggers and critics point them out over and over, but through aggressive economic reform of the film industry that starts with a scorched earth antitrust policy and never looks back.

However, La La Land’s treatment of nostalgic themes and the critical response to those nostalgic themes are an important case study in how the political capture of popular criticism by liberalism has resulted in a chronic inability to grapple coherently with both nostalgia and the entire body of art that predates the most recent three decades at any given moment.

The Whig interpretation of history is the idea that the history of the world is the history of an inevitable progression towards ever greater justice, liberty and equality through the continuous development of human reason in the general population. Bluntly, the Whig interpretation of history is bullshit. Mostly because it replaces the constant struggle of marginalised people to win political victories and change the moral values of society to secure them long-term with an imaginary history where the world got better because people got smarter, but also because history is full of huge setbacks to movements for human rights and social justice. The Voting Rights Act of 1965, which attempted to end the disenfranchisement of black voters in the US, has been gutted piece by piece for decades, culminating in Shelby County v. Holder, a decision by the Supreme Court that effectively abolished the VRA’s enforcement mechanisms. Similarly, the US pro-life movement has spent the past three decades successfully rolling back every abortion rights victory since Roe v. Wade through zoning laws and other legal instruments. There are few countries in the world where a once generous welfare state hasn’t been whittled down to almost nothing by austerity, privatisation and means-testing, and the Chechen regional government is openly committing genocide against its gay citizens. Ireland will soon have a Thatcherite Taoiseach, an equitable peace between Israel and Palestine seems like a more foolish dream every day, and fascism is back as a viable political ideology across Europe and North America.

We’re living in the midst of catastrophic setbacks to human rights right now, and have been for some time, yet the Whig interpretation of history still holds sway within liberal ideology, because to admit the Whig interpretation is wrong would be to admit that liberalism has failed on a massive scale and requires a reckoning with that failure that liberals are unwilling to undergo.

Because the Whig interpretation presupposes the stupidity of people in the past and the cleverness of people in the present (relatively speaking, at least), there is a taboo against ever suggesting that anything in the past was better than the present, and therefore an attitude towards nostalgia that’s dismissive at best and contemptuous at worst, with an arsenal of spurious arguments to discredit the validity of ideas, policies and art based on little more than the time they existed. It’s what’s happening when people use the accurate critique of the racism that underpinned Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal to attack those who support a strong non-racist welfare state in the present day, or to claim such a welfare state is impossible because the right exploited racism to roll it back, even though we’re supposed to be less racist now, so it should presumably go much better this time. It’s what happens when someone comments on a picture of a poodle skirt saying they love 50s fashion and someone else gravely informs them that they wouldn’t like being unable to have a career because in the 50s most women were expected to leave the workforce after marriage. It’s what’s happening when people call La La Land racist or sexist for its nostalgic themes.

Both the kind of musical films that La La Land evokes and the specific musical films it references are from time periods in which many marginalised groups (e.g. black, gay or disabled people) had fewer legal rights than they do now, were subject to more political violence and had worse economic outcomes. Employment discrimination was far more widespread, whole areas of society were legally segregated, eugenic practices like forced sterilisation were common and ethnic minorities were targeted in state-sanctioned lynchings and pogroms. Government agencies worked both overtly and covertly to destroy any organisations working to improve the lives of such people, especially socialist and communist parties and other left-wing organisations like the Black Panthers or Students for a Democratic Society, often in collusion with religious authorities (e.g. the Catholic Church’s long shameful history of opposing state provision of public goods in Ireland) or far-right extremists and terrorists like the Ku Klux Klan in the USA, or the Ulster Defense Association in Northern Ireland. No one can or should separate art from the material conditions of its historical context, and so it’s absolutely true that Singin’ in the Rain exists in part by virtue of Jim Crow, if only because a parallel world where seventy years of legal segregation never existed would be so radically different as to practically guarantee no piece of art that exists in our world would ever exist there. But articles like this piece of crap from Salon try to make an unjustified leap from these obvious facts to spurious conclusions about La La Land by disguising a lack of coherent argument with cheap linguistic tricks.

Take for example the line that says that because Sebastian (Ryan Gosling) loves classic jazz and wants to keep its spirit alive that means “he pines for a time that has passed, both musically and culturally — a time when he might have more easily swept Mia off her feet.” Tons of logical leaps are smuggled in here. Sebastian’s love of an approach to art rooted in a certain historical context and desire to keep that approach to art alive is transformed into a pining for the historical context itself, and then even more specifically for the greater imbalance of power in straight romantic relationships that existed in the same historical context, with no justification in the line or anywhere else in the article for making those jumps, because the article presumes no justification is necessary – after all, everyone agrees the world just gets better and better in every way, so to ever show appreciation for anything from the past is to secretly show appreciation for everything from the past.

Except, of course, it’s not, and no one really believes that, which is what makes the way liberal critics talk about nostalgia so utterly incoherent. The Whig interpretation of history is built into their worldview and can’t be rooted out without a revolution in their perspective – to abandon the Whig interpretation is to admit the liberal ideology of technocratic procedural democracy and free market enterprise has failed to reliably improve the world year-on-year. Such an admission entails a reckoning with liberalism’s failure that liberals refuse to undertake, yet it’s a simple fact of life that anyone who cares deeply about an art form almost certainly pines for aspects of how that art form was practised in the past that haven’t survived to the present day, like matte painted backgrounds in film. Nothing short-circuits liberal criticism more devastatingly than this contradiction. Almost any critic would agree popular cinema is in a prolonged state of crisis right now as it continues to be dominated by samey superhero movies, heartless children’s films and cash-ins on any and all recognisable intellectual property, films that are less films than products, but if you dare make a movie that looks fondly back on musical films from a time when musical films were both popular and excellent, those same critics will call you racist (or, if they’re afraid to take on the risk of a strong stance, accuse you of “unintentionally trafficking in worrying attitudes to race” or something similarly qualified), even though they also like those musical films and agree it was better when good musical films were popular cinema instead of Suicide Squad.

The liberal critical commentariat is not just incoherent in response to “nostalgic” art, but also extremely selective and arbitrary in where it directs its ire and what injustices it takes up. Anyone with a decent English degree from an adequate university could tell you how the novel’s existence is dependent on the violent extraction of wealth from the colonies of European empires which created the original middle class of merchants, civil servants and other professionals with both the means and free time to read where previously such luxuries were limited to the upper class, but the book critics of the world have never fueled a seasonal thinkpiece boom with handwringing articles about whether Michael Chabon’s new novel is secretly nostalgic for the heyday of the East India Company. No one has ever responded to appreciation for films from the Golden Age of Hollywood by accusing anyone of secretly being nostalgic for the Third Reich, since so many great directors, screenwriters and actors of that era came to Hollywood fleeing the Nazis. Most of all, appreciation for contemporary works of art is never taken as de facto appreciation for contemporary systems of oppression – Hidden Figures only exists because those who funded its creation own capital at the expense of those who starve, but I’ve yet to see anyone accused of being pro-starvation because they like Hidden Figures. Maybe it’ll happen in fifty years, when an appreciation for Hidden Figures is magically transformed into nostalgia, but it still won’t make sense. Or maybe by then someone will have made a persuasive argument that a fondness for the art of the past entails a fondness for the injustices of the past. No one has made it yet.

What make this all the more maddening is that La La Land is a movie with an extremely complex and ambiguous relationship with nostalgia that struggles with serious questions about art. Sebastian is often characterised in criticism of La La Land as a purist while his collaborator Keith (John Legend) is an innovator, but both are concerned with the same problem: jazz was once a popular art form that’s now considered niche and pretentious. Sebastian wants to open a jazz club where people can come see the music, but Keith points out that the clubs where he plays now don’t attract young people who can form the base of a new age for jazz as a popular art form – why would Sebastian’s own club do any better? He points out that the artists Sebastian loves and emulates like King Clark and Thelonious Monk were revolutionaries in their own time. Then he asks the question at the heart of everything the film wants to say about art:

“How are you gonna be a revolutionary if you’re such a traditionalist?”

Critics of La La Land’s portrayal of jazz often cite this moment as the only time in the film it pretends to think Sebastian and Keith both have a point, because Keith’s fusion jazz band plays bad music and that proves the film is on Sebastian’s side, which is also an example of La La Land’s bad racial politics. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar was “disturbed to see the one major black character, Keith (John Legend), portrayed as the musical sellout who, as Sebastian sees it, has corrupted jazz into a diluted pop pablum” because it’s distasteful that the “white guy wants to preserve the black roots of jazz while the black guy is the sellout”.

This is the most embarrassing misreading of La La Land in a very deep pool of shallow thinkpieces, not least of all because the only song we see performed by Keith’s fusion jazz band, “Start a Fire”, is really good. Mia (Emma Stone) even says she likes their music, she just doesn’t think Sebastian does. Critics who said it was so obviously terrible it proved the film agrees with Sebastian have done less to show that Damien Chazelle is a jazz snob than expose themselves as jazz snobs.

La La Land offers no answer at all on whether Sebastian or Keith is right, since it ends with Sebastian running his club and Keith presumably still in his fusion jazz band and gives no indication that either of them have saved jazz from its present obscurity. It’d be bizarre if La La Land had picked a side one way or the other because everything it says about jazz isn’t just about jazz, it’s about art in the broadest sense, movie musicals and La La Land itself. La La Land is a film where Damien Chazelle asks questions of both himself specifically and artists generally, all of whom are influenced by art from the past. Is it possible for me to preserve and honour and continue what was once great about the form I work in or is it lost forever? Can I bring the magic of the movie musical back to life in the present day or can I only pay tribute? Is it possible to make new masterpieces in old forms or is new art only worthwhile if it pushes the medium forward?

How can I be a revolutionary if I’m such a traditionalist?

La La Land is an attempt to answer that question, but it doesn’t pretend to know which answer it gave. It doesn’t presume its own success at charting a course through these essential debates about art’s relationship with its own heritage. It leaves the final judgement to its audience.

Unfortunately, liberal-inflected criticism has proven itself unable to parse a film that takes the artist’s struggle with their own nostalgia so seriously, because it can’t take the past seriously as long as the distorting lens of the Whig interpretation constrains its understanding. Artists should be praised for ambition and innovation, whether thematic, formal or technical, but there’s little room in contemporary criticism for art that’s simply an excellent example of a form that consensus has dismissed as dated, like the multi-camera sitcom. Even the best-received of recent multi-cams, One Day at a Time, was more likely to be praised for “overcoming” its form than for doing it well, and neither The Ranch nor Superior Donuts received any such back-handed compliments, despite being great in their own right. Critics are quick to toss aside anything they’ve seen before, anything that doesn’t challenge or surprise them but simply does what it does sincerely and well. For my part, I think a blossoming flower is still beautiful to behold even if you know what’s going to happen to it, and there’s a joy in simply watching a great artist execute the form well.

La La Land is doomed to be misunderstood as long as popular criticism remains trapped in the prison of liberalism, unable to honestly deal with questions that at least raise the possibility there might be things from the past that aren’t around anymore but might be worthwhile. This disregard for the treasures of our past is a poison that rots everything liberalism touches, whether it’s the deep ignorance of how radical political struggle helped to combat the AIDS crisis among young LGBT rights activists, the disinterest in reviving anti-trust laws among the liberal political class or the dismissal of any art form that’s not judged as sufficiently boundary-pushing, from multi-cams to pop punk to screwballs. It’s part of what motivates the liberal critic’s contempt for art that deals seriously with questions of faith because faith is seen as quaint and antique in the liberal imagination, yet leads them to valorise formally innovative art while never engaging seriously with its themes.

Modernity is an island in time where we’re so disconnected from our collective past that we write panicked screeds about how the Trump presidency is an unprecedented assault on American democracy as if there weren’t decades when US intelligence agencies were engaged in massive conspiracies to disrupt, imprison and murder political protestors in their own country. Or worse, we know our history, and pat ourselves on the back for knowing, but sit so comfortable in our surety that the world is getting better that we never think to ask if this history we know has any lessons we could learn. We are the Irish who know the Great Famine was only so deadly because the British government didn’t intervene out of a fanatical belief in the free market, but never allow ourselves to be moved by our history to end starvation in our country now, because that would mean raising taxes. In a few years, the unprecedented world-ending catastrophe of the Trump administration will be deemed a blip in history, a wobble in the otherwise smooth arc of the moral universe and no one will have to ask uncomfortable questions about how liberalism could fail so drastically to keep fascists out of the White House. Yet sometimes we’ll call a movie that evokes the movies of the 40s racist because there were less roles for black actors in the 40s, and not because of any particular racist content.

If only there was a film about this troubled relationship with the past.

Part 4 – “Where I Come From, The Past Is Something to Forget, But Here It’s All You Talk About.”

T2 Trainspotting is the poorly-titled sequel to Danny Boyle’s Trainspotting, one of the most iconic films of the 90s. Reviews were generally positive, including some good notices for its nuanced exploration of nostalgia, though some critics interpreted it as a shallow nostalgia trip for Gen-Xers. Mixmag concluded it was unlikely we’d “still be talking about this film in 20 years…or two months, even”, which turned out to be true, though not, as they suggest, because T2 is not worth talking about. Once again, a film that dares to deal seriously with nostalgia gets a consistently unserious response, with faint praise that it’s “surprisingly fun” despite being less “ambitious and provocative”, or that it’s only half “nostalgic shite”. Many reviews commit the stupid error of criticising nostalgia while being nostalgic, critical of T2 for not being more like Trainspotting when it’s very much the point that T2 is a different film, or bungle the comparisons between the first film and the sequel with nonsensical readings like “Carlyle’s Begbie was a rebellious cowboy in the first film; here he’s a cipher for unrestricted rage” that betray a narrow, skag-tinted lens.

T2 is the film that inspired this entire article and that’s because it knows better than any film I’ve ever seen that nostalgia arises from a sense of dislocation. Renton (Ewan McGregor) returns to Edinburgh after a heart attack and before an impending divorce, and interrupts a suicide attempt by Spud (Ewen Bremner), who ended up back on heroin when his ignorance of Daylight Savings Time caused him to lose his job, his dole and his visitation rights with his son, Fergus. Begbie (Robert Carlyle) escapes from prison and tries to resume his career as a criminal with his son, Frank Jr, who just wants to do well in his hotel management course. Sick Boy (Jonny Lee Miller) has moved from heroin to cocaine and makes a living by blackmailing middle-aged men with tapes of his girlfriend Veronika (Anjela Nedyalkova) pegging them. He’s the most vocally critical character in the film when it comes to nostalgia, but only because he’s been stuck in place for twenty years and so has less to be nostalgic about.

“Nostalgia, that’s why you’re here,” he tells Renton when they travel to the countryside with Spud to pay tribute to Tommy (Kevin McKidd), who died in the first film. “You’re a tourist in your own youth.” He points out that Tommy died a drug addict because Renton gave him his first hit, as if Renton doesn’t already know, as if Renton didn’t come out of a sense of duty to the friend he killed. Renton shoots back that Sick Boy let his own baby die because he was too doped up to pay attention to her. T2 and its characters mine their history by all means, but rarely is it the kind of masturbatory callback that pollutes films like Ghostbusters (2016) or Jurassic World, references that listicles call “Easter eggs”, a term that once described messages or jokes hidden in video games by their developers that players were challenged to uncover, but now apparently applies to explicitly casting Jimmy Smits to play the same character that he played in the Star Wars prequels in a film set between the prequels and the original trilogy. T2 knows its existence leverages nostalgia for Trainspotting, but it uses that as an opportunity to ask interesting questions about nostalgia.

T2‘s version of the “Choose Life” monologue juxtaposes the callback to the previous film with a vicious reversal of the original monologue’s cynicism, with Renton moving from blithe disdain for a timeless consumerism (“Choose handbags, choose high-heeled shoes, cashmere and silk, to make yourself feel what passes for happy”) to more recent cultural maladies (“Choose live-blogging, from your first wank ’til your last breath; human interaction reduced to nothing more than data”) to real contemporary social problems tinged with personal pain (“Choose a zero-hour contract and a two-hour journey to work. And choose the same for your kids, only worse, and maybe tell yourself that it’s better that they never happened”) before concluding with heartbreaking earnestness:

“Choose unfulfilled promise and wishing you’d done it all differently. Choose never learning from your own mistakes. Choose watching history repeat itself. Choose the slow reconciliation towards what you can get, rather than what you always hoped for. Settle for less and keep a brave face on it. Choose disappointment and choose losing the ones you love, then as they fall from view, a piece of you dies with them until you can see that one day in the future, piece by piece, they will all be gone and there’ll be nothing left of you to call alive or dead.”

Nostalgia arises from a sense of dislocation and increases in times of social upheaval, just as drug abuse increases in times of social upheaval. When your life is overthrown, even the worst of your past can gain a fresh warmth in your mind. You might have been a heroin addict whose friends died, but at least you had friends. When Renton first stops Spud from killing himself, Spud screams at him: “You ruined my life, and now you’re ruining my fucking death too!” But minutes later, he’s reassuring Renton that he won’t try to kill himself again, not while his best friend is in town. Later, Spud is standing alone in the street after a failed attempt to replace heroin with boxing on Renton’s advice. In one of the most breathtaking images I’ve seen in a film, he watches himself and Renton running down the same street as teenagers, shortly before they’re nabbed for theft and Spud is sent to prison for the first time. Even in this moment just before one of the many events that led him to this low place, Spud finds a kind of beauty in the memory, and it’s part of what inspires him to take Veronika’s advice later in the film to start writing down the tales of his youth, to grapple with the story of how his life was ruined in a time that nonetheless contains some of his happiest memories.

Spud’s hand-written reminiscences become pivotal to the film both narratively and thematically. Begbie comes to Spud’s apartment in search of Renton and lives vicariously through his young self as Spud reads him the bar fight from Trainspotting (“That lassie got glassed, and no cunt leaves here ’til we find out what cunt did it!”). He reflects on his failure as a father when Spud recounts the day they ran into Begbie’s alcoholic father living in the derelict Leith Central Railway Station, a scene from the original novel that inspired its title, but wasn’t included in the original film. Momentarily quelled, Begbie’s desire for revenge against Renton is reignited when Spud’s final story reveals that Renton secretly left some of the money he stole behind for Spud. Begbie sets out to kill his old friend, though the memory of his father inspires him to first pay Frank Jr one last visit, apologise for his failure and wish him well at his college course. Nostalgia invigorates Begbie, trauma haunts him, and grievance enrages him.

During the final confrontation, when Begbie has him trapped in an unfinished booth in the construction site for Sick Boy’s brothel, Renton tries to appeal to their shared history.

“I remember my first day at primary school. My very first day, and the teacher, she said ‘Good morning, Mark. You can sit here, next to Francis.’”

The camera switches to an overhead view. Renton and Begbie are momentarily replaced by their childhood selves, who look up to the ceiling. The camera cuts back to the adult Begbie, his face mournful.

“Mind that Franco? You were older, you’d been kept back.”

Begbie remembers.

“I mind that well enough.”

Renton thinks he’s getting somewhere. “Aye. We had it all before us, didn’t we? Had it all still to come.”

The camera cuts back to the overhead shot of Renton and Begbie as children, their places in the frame swapped.

“And now here we are,” Renton concludes.

“Aye, you’ve done all right,” responds Begbie. “World’s alright for smart cunts, but what about me? What about fucking men like me?”

Renton has fucked up. A sweet memory for him is a painful reminder for Begbie that he’s never lived in a world where he had a fair chance to make a good life.

“What do I get?” Begbie continues. “What I can take with my bare hands, or I can get with my fists.”

He picks up a sledgehammer.

“Is that what I fucking get?”

He hammers a hole in the wall of the booth and sticks his head through.

He growls at Renton.

“Who’s a fucking smart cunt now?”

T2 is an anti-nostalgia film that treats it as a feeling with the potential to be as addictive and destructive as drugs, but it doesn’t condemn those whose nostalgia, or drug addiction, arises from pain for seeking out salves to sooth their souls. T2 understands that nostalgia is a way of processing the relationship between our present and our past. As Danny Boyle put it in an interview with Consequence of Sound:

“Well, nostalgia is a much maligned word. We imagine it as weakness or sentimentality. In fact, he gets accused of it. It’s a great line. Everybody quotes it: “You’re just a tourist in your own youth.” Of course, what it is, as well, if you rename it – it’s the past that’s alive in all of us. Our past is alive in us. You cannot erase it, and people who do are very, very dangerous people, who refute the past and rewrite history. Be careful. There’s a terrible road that leads from that.”

Halfway through T2, after Renton and Sick Boy have lectured Veronika on the cultural significance of George Best’s tenure as a striker for Hibernian F.C. (we don’t hear their full explanation, just snippets like “the end of austerity” and “the first McDonald’s opened in the UK”), she responds in Bulgarian that “where I come from, the past is something to forget, but here it’s all you talk about”. It’s the only part of the film that rings a little hollow, because even in post-communist Eastern Europe, there is nostalgia, especially in recent years when capitalism has failed to deliver on its promises to the former Soviet bloc, and especially in Bulgaria. We all need to reckon with how our present moment has failed to live up to expectations, and reckon with how the failures of our past as well as our abandonment of its successes has brought about this present state of prolonged, managed decline, “unable to imagine or countenance any ambition beyond tinkering with the present hell, committed only to the endless dogmatic repetition of the sameness of the world”. It’s fitting that T2 ends with Renton, Sick Boy and Begbie back where they started, while Spud is moving forward with hope, because he’s the only character who’s really taken stock of his life and history.

Naturally, liberal critics have largely failed to appreciate the scope of T2’s inquiry into nostalgia, or offered befuddled responses. The review that said T2 was only half “nostalgic shite” also claimed that the characters returned with “a clearer self-understanding of their place in society” but two sentences later that “there’s even less place in society for these downtrodden characters”. The Telegraph managed to muster a superficial overview of how the film portrays shifts in the dominant cultural expression of masculinity over the past two decades. Even glowing reviews like Mark Kermode’s did little to touch on its grander social themes, despite some occasional gestures toward acknowledging it contained any at all.

But at least if liberal criticism is doomed to always botch its engagement with nostalgic themes, its viciousness towards the past surely means it never lets anything off the hook, right? Right?

Right?

Part 5 – Against Stranger Things

Stranger Things is the most heartless, vapid, cynical, repulsive television show of the last year. If ever a piece of pop culture deserved to be crucified in the public square for its cheap, plodding, hollow rehash of beloved movies from the past, this is it, a dull and nasty show that scrubs its source material of all social context and regurgitates it piece by piece without even the added flavour of its own bile. The worst thing about Stranger Things is that it has neither the ambition to be innovative nor the passion to be excellent. Instead, it is a punishingly mediocre artwork that should warrant no reaction except immediate deletion from our collective memory. I understand the pleasures that Stranger Things offers to a viewer. It’s a well-paced jog down memory lane that lets you see a badass little girl flip a van in the air with her mind. Most of the performances, especially those by the child actors, are genuinely compelling and it even has one neat idea, when Will tries to communicate with his mother through her Christmas lights. Taken as a whole, its popularity is not that surprising, but its critical reception is baffling.

This perfect encapsulation of everything that liberal critics say they hate about nostalgia received universal acclaim. “Stranger Things Is Nostalgia That Works,” declared Time, though the reviewer struggles to actually describe why it’s good. He calls it “a show whose fondness for its own source material makes its nostalgia warm and inclusive”, which is a heck of way to make the most uncritical nostalgia porn ever made sound like it has a heart. This Salon review is nothing less than a masterpiece of self-deception, in which a reviewer publicly talks himself into pretending Stranger Things has any artistic value, even conjuring up a deeper meaning to its appeal out of thin air:

“Yes, the “Stranger Things” creators pillaged my beloved ‘80s pop culture. But despite all the pointed shout-outs the Duffer Brothers crammed into the story, the series never feels like a soulless knock-off or a pointless nostalgia trip.

Forget my initial grumpiness. I truly love the show, and so should you. Yet I wonder if there’s more to its appeal.

Perhaps the Duffer Brothers didn’t want to only create an homage to vintage pop culture. They’ve recreated a world when things were simpler (and yet at the same time, much more complex — see: “the upside down.”) To create a story-space for Millennials to journey back to the pre-digital, tactile world before the Internet, before smartphones, Tinder and Pokémon Go. A time before helicopter parents over-scheduled their children’s lives, when “afterschool program” meant the freedom to ride your bike to a quarry or a junkyard and get into trouble, or just hang out with your buddies in the basement, scheming.”

The review concludes, as so many do, with a weak gesture toward acknowledging its shallowness (“the 1980s weren’t all that simple”), but no serious criticism of its portrayal of the time period. This absence is a recurring theme of Stranger Things criticism, even or especially in the rare dissenting takes. Stranger Things is never particularly bad, it just represents the evil of nostalgia generally with its pleasantly white world with just enough female characters and token minorities (exactly one) to assuage the liberal conscience. Stranger Things is never criticised for ignoring racism in a show set four years after the 1980 Miami riots against police violence, and just a year before the Philadelphia Police Department bombed and burned a black neighbourhood to the ground in a standoff with a black liberation group resisting arrest on trumped-up charges, even though 80s films are commonly and fairly criticised for their whiteness and disinterest in racial issues. Stranger Things is never criticised for papering over class-based conflict and bullying among schoolchildren and teenagers with the cool kids vs losers bullshit typical of the post-Clueless films that replaced the class-conscious teen films of the 1980s like Pretty in Pink and Dirty Dancing. Stranger Things is never criticised for its genuinely weird gender politics, with the androgynous Eleven becoming more humanised as she allows the boys to visibly gender her as a girl with a dress and wig that make her looks like a doll, perhaps the only makeover in the 80s more stupid and ill-considered than Allison’s in The Breakfast Club. The only review I could find that even hints at the possibility there might be some specific worrisome political content in Stranger Things worth thinking about is this New Yorker article and even that bases all its claims on Stranger Things’ relationship with the works of H.P. Lovecraft, and not on the content of the show itself.

If nostalgic art is so inherently racist that La La Land is fascist propaganda, then Stranger Things should have been cast down as a personal tribute to Hitler, but just as we assume our own nostalgia is so much more nuanced and self-aware than others, we also assume any art that appeals to our nostalgia is harmless without really examining its nostalgic elements critically. Stranger Things was not cast down and it will not be forgotten, but will persist for many years to come, churning out the same tired artless crap it did in its first season and getting praised for it every time, with the exception of the odd contrarian take about how it should have been a miniseries. It will neither push the medium forward nor pass any commentary on the films it draws on. It will never be a new masterpiece in an old form, and it will be praised nonetheless for the mild dull pleasure it provides, the artistic equivalent of soaking in a lukewarm bath. But it will also remain an anomaly, as hundreds of authors spin gold from thinkpieces criticising the nostalgia industry or reviews dismissing the value of art because it’s nostalgic at all and not because it’s nostalgic in any particular way. Worst of all, these authors and their editors will never own up to the fact that they’re trying to profit from nostalgia as much as anyone, because for every “mindless” nostalgia lover who clicks on a listicle of “20 things you’ll only remember if you grew up on the outskirts of Ljubjlana in the 1970s”, there’s an equally “mindless” nostalgia hater who’ll click on your explanation of why some film is racist because it evokes the weepy genre, and the weepy genre is from the past, and everything about the past is bad.

In Save the Tiger, Harry Stoner is nostalgic for the past because he’s been torn away from it by bullets and bombs and blood. He hasn’t been able to carry forward the good and leave behind the bad. It’s all gone. I hate to think of how Save the Tiger would be received today, because it’d take the form of a thousand thinkpieces about how it critiques white masculinity by showing Harry pathetically yearning for the past and being mocked for it by his wife and peers. I don’t even think they’d be totally wrong, though a little callous and not that interesting. But they’d never stop to ask if maybe he has a point, if maybe there was something precious lost when the baseball players stopped putting the spikes of their cleats right in your face.

I don’t know if he does, but it’s worth taking the question seriously.

3 thoughts on “What We Talk About When We Talk About Nostalgia”