M. Night Shyamalan knows that you know who he is – or, at least, that you think you do. He’s the twist guy! His early work, particularly The Sixth Sense and Unbreakable, received such acclaim that Newsweek declared him “The Next Spielberg” in a cover story published three days after the release of Signs. It’s a cliché of latter-day Shyamalan coverage to contrast this praise with the direction of his subsequent career, as the diminishing returns on his work turned him from wunderkind to has-been.

He’s since made a proper comeback, with the runaway success of Split, which sucks, but back in 2015, he was still a joke. A literal punchline, a memetically bad writer and director, whose most recent movie, After Earth, was a sterile, indulgent pile of crap based on an idea by star Will Smith, operating at the height of Smith’s ego. His previous three films – Lady in the Water, The Happening and The Last Airbender – regularly appeared on lists of the worst films ever made. But, most importantly, he was the twist guy. So the story goes, he got so much praise for the genuinely brilliant twists of his early work that he couldn’t stop chasing the same high, trying to outdo himself with each film. It doesn’t matter that this isn’t true – it’s astonishing how many people have made fun of the twist in The Happening, a film that does not have a twist – because it quickly became the totalising narrative of his career. Particularly on the Internet, his shittiness and this specific explanation for his shittiness became the conventional wisdom, in much the same way that memes and groupthink convinced people Nicolas Cage is one of the worst actors in the world, rather than the best of his generation.

M. Night Shyamalan is the twist guy. Except he’s not. But he knows you think he is. So, back in 2015, he decided to play a prank on everyone. It’s called The Visit and it was his best film in fifteen years, so obviously it got wildly mixed reviews. People’s brains just go all wobbly when it comes to this guy, for some reason.

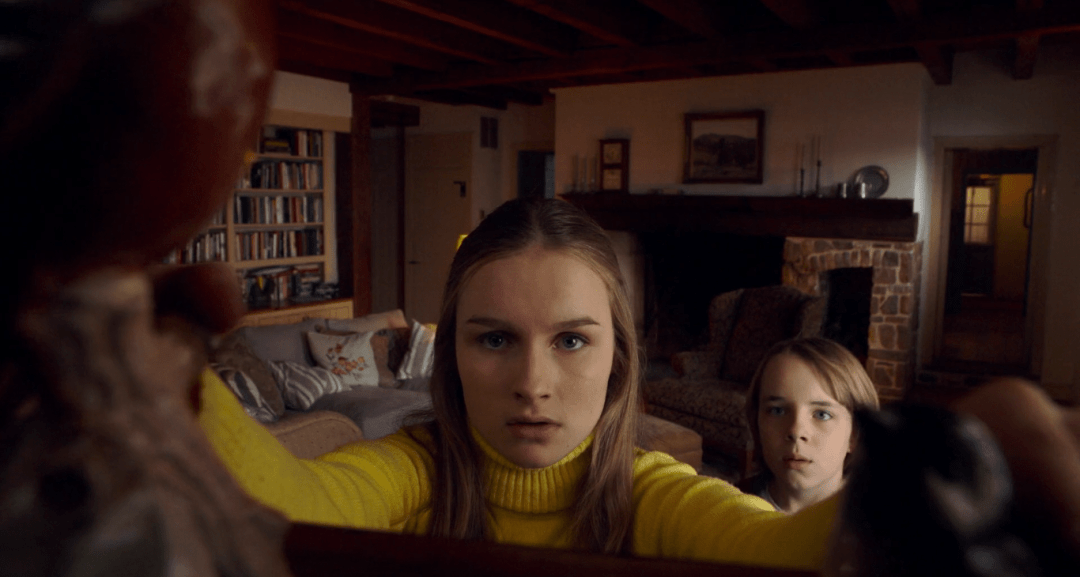

The Visit is, in a lot of ways, a very simple film. Teen siblings Becca (Olivia DeJonge) and Tyler (Ed Oxenbould) travel to a small town in rural Pennsylvania to visit their grandparents, Maria (Deanna Dunagan) and Frederick (Peter McRobbie), while their mother Loretta (Kathryn Hahn) goes on a cruise with her new boyfriend. Maria and Frederick have reestablished contact after throwing their daughter out fifteen years prior, and though Loretta isn’t much interested in a relationship herself, she wants her kids to have a chance to know them. Becca is an aspiring filmmaker, so she brings a camera along to make a documentary about the family reunion. Tyler is an aspiring rapper, but it’s not relevant to the plot, it’s just hilarious. The siblings get spooked by weird stuff their grandparents do and eventually discover that their “grandparents” are two escaped patients called Clare and Mitchell from a nearby mental hospital where their real grandparents volunteered as counsellors, having killed the real Maria and Frederick in order to spend some quality time with and ultimately murder Becca and Tyler. The kids survive, their mother gives them a touching lesson about forgiveness, and then Tyler raps over the credits. It’s hardly reinventing the wheel when it comes to its plot, but it does something really interesting with how it tells its simple story.

I said earlier that The Visit received mixed reviews, but it’d be more accurate to say it got polarised reviews. Some people, like me, loved The Visit and called it, at the very least, a strong return to form, if not one of his best films. Some absolutely hated it, like Mark Kermode, who said Shyamalan “may actually have made a film worse than Lady in the Water”. (Only Christopher Orr of The Atlantic seemed to find it merely mediocre.) And although I found Kermode’s review of The Visit pretty shallow and dismissive, I also understood exactly where he was coming from, because he correctly identified the most pertinent features of the film. He just hated them.

First, the movie is told in found footage style. The Visit arrived very late in the life cycle of the genre, and most negative reviews criticise the film merely for being a found footage horror. But The Visit is really great at being a found footage movie. Cinematographer Maryse Alberti makes it feel as much as possible like a film actually shot by two precocious children, including giving each one a distinctive style, without letting it devolve into the nausea-inducing shaky cam of films like Cloverfield. Most importantly, The Visit constantly draws attention to its genre in a way that enriches its storytelling. Becca is constantly explaining basic precepts of filmmaking to Tyler, and tries to adhere to a strict ethical standard of only filming events she’s participating in. Where Tyler just kind of looks around for interesting things to point the camera at, including the inside of his own mouth, Becca wants to make an effective movie. “We’re looking for visual tension. Things that pull the frame, things that force us to imagine what is beyond the frame.” It’s a cheeky line for a film that clearly wants you to constantly think about what is beyond the frame, not just in terms of the visual information it hides from the audience to preserve tension, but in terms of its genre and its director. The Visit wants you to watch it in a certain way, as a horror film and an M. Night Shyamalan film, so it makes you think about it constantly. Like when someone tells you not to think about elephants, so elephants are the first thing you think about, The Visit’s characters talk all the time about Becca’s film, which immediately prompts you to think of Shyamalan’s.

Second, the movie’s protagonists are children. Kermode finds the protagonists so annoying that it’s hard to believe he could enjoy the film even if the rest of it were to his taste. The kids, in fact, seem to be the most polarising part of The Visit, either charming, genuine and funny or just the worst pair of human beings recorded on motion picture. I though they were great, but regardless, what matters most is that they are children, and that the film forces us, through the found footage genre, to see the events from their perspective, literally and figuratively. Much of the unnerving behaviour from their “grandparents” that freaks them out turns out to be just red herrings. Clare has dementia and suffers from an extreme case of “sundowning”, her symptoms worsening severely at night. Mitchell is incontinent and wears adult diapers, which he stashes in the barn out of embarrassment. The kids get scared by it, particularly Tyler, but then Mitchell (more lucid than Clare) or Loretta or even Becca will point out that it’s just the kind of upsetting stuff that can happen to older people.

The effect is to put the audience in a position of doubt and uncertainty as to what’s actually a sign of something seriously amiss and what’s scary from the kids’ point of view, but indicates no real threat. When the film already primes us to be hyperaware of Shyamalan and his reputation for twists, it starts to inculcate a kind of paranoia about figuring out what’s going on. The film throws so many unsettling things at the audience, and so much of it is misleading that you begin to feel as confused as the protagonists. Clare chases Becca through a crawlspace under the house and Becca is terrified, but Clare actually is just playing with her, and when the kids mention it to Loretta, she fondly recalls doing the same when she was a kid. Becca walks in on Mitchell apparently about to kill himself with a shotgun, but he reassures he was just cleaning it, and it’s obviously not true, but it also doesn’t do a lot to point you towards the reveal. Clare and Mitchell aren’t planning to kill the kids until the final night of their stay, so lots of apparently threatening things, like Clare asking Becca to climb inside her very large oven to clean it properly, have nothing to do with what’s really happening, but it sends you on a mad scramble for Hansel and Gretel references. The most effective example, for me, at least, is when Clare tells a “story” about tiny aliens from the planet Sinmorfitellia that live in water and spit a substance that “can make you fall asleep, but not die”, I started wondering if she and Mitchell were alien doppelgangers, not just because of what she said, but because she said it as a character in an M. Night Shyamalan film and he’s previously made a movie about aliens where water plays a large role in the plot. It turns out to be relevant because Clare actually believes that story and drowned her two children in a pond, but in the context of so much other weird stuff pointing you in different directions, it doesn’t stick out.

Third, the movie swerves wildly between horror and comedy. Again, some found this off-putting, like the film didn’t know what it wanted to be. Others, like me, loved it, because it played with the close connection between laughter and horror. “Horror is very close to comedy,” writes Sheila O’Malley in her positive review for RogerEbert.com. “Screams of terror often dissolve into hysterical laughter, and [Shyamalan] uses that emotional dovetail, its tension and catharsis, in almost every scene.” He does something similar in The Happening, applying the rhythm of comedy to scenes of horror – like a chain of people killing themselves with a revolver – to produce that special “laughing, but I know I shouldn’t be laughing” kind of humour. The Visit takes it in a different direction, featuring so much humour for its own sake and turning so many scary moments into funny ones that you kind of start to doubt you’re watching a horror film at all.

The jokes mostly come from Tyler, not just his dumb, funny rapping, but also stuff like his decision to reduce how much he curses by saying the names of female pop singers instead of swear words. It’s an extremely stupid running gag and it’s hilarious and has nothing to do with the plot. Also, his rap name is T-Diamond Stylus and sometimes Mitchell calls him that in complete seriousness and it makes me laugh every time. Meanwhile, in terms of moments that uncomfortably straddle the line between horror and humour, you have the aforementioned oven-cleaning and Clare’s obliviousness about how creepy she’s coming off, or the crawlspace scene. It’s scary at first, but when Clare comes out from under the house laughing, you immediately question whether it’s a hint of horror to come or just…an old lady messing with her “granddaughter”. Even with the weird way Clare went about it, it’s still totally within the bounds of normal behaviour. Adults run after kids pretending to be monsters all the time. It’s a bit odd to do it to a teenager, but, when we still think Clare is their grandmother, it kind of comes off well-meaning and a little sad, like she was trying to catch up on the kind of playtime she missed when they were estranged. There were plenty of moments in The Visit where I started to wonder if maybe the twist wasn’t going to be that there was nothing sinister afoot, so I understand Mark Kermode’s confusion over whether it’s supposed to be a horror or a comedy to a certain extent. The film deliberately tries to make you question if it isn’t actually a dark comedy. I’m just not sure why he was still confused when the film ended.

But I think you can find a clue in his later review of Split, where he says he’d be more forgiving of the film if it was made by an up-and-coming filmmaker rather than an established director who’s made great films in the past. Shyamalan’s shadow looms large over The Visit and he knows it, but rather than be doomed by his latter-day reputation, he leans into it and tries to use it as a way to get one over on the audience. You start The Visit knowing – or thinking you know – that there’s gonna be a twist. For some, like Kermode, that prospect is treated with a kind of dread. But when approached with curiosity, the mystery propels you into the character’s headspace, this position of anxiety and confusion that leaves you doubting yourself and your intuitions. That’s how the movie was for me and friends of mine who watched it. The difference of experience seems to be heavily informed by one’s disposition toward Shyamalan himself, and, of course, that’s exactly what The Visit depends on. It wants you to watch it in a certain way. It wants you to watch it as an M. Night Shyamalan film.

For better or worse, it succeeds.

One thought on “What is Beyond the Frame”