This article is part of the Notes on Failure series, which discusses interesting cinematic failures. Previously, notes on Split.

Sometimes a film is so set up for me to like it that nothing speaks to its failure like my thinking it’s only okay. It might tick a bunch of boxes of things I reliably enjoy, like Hell or High Water, a neo-western about the Great Recession featuring comedic bank robberies and a great performance from Jeff Bridges, one of my favourite actors. It might be targeted at a very specific niche of which I am a part: Mary Magdalene was described as not appealing to Christians because it’s such a different take on the Gospel story, and not appealing to non-Christians because it’s so religious, but I’m a feminist Christian whose favourite film is The Last Temptation of Christ, king of unorthodox Gospel films. It’s kind of heartbreaking, when a film stacks the deck so in favour of me loving it, as if it was made with me in mind, but fucks it up so badly that I think “it’s basically fine, I guess, I don’t know, it has some problems.”

Hamlet (2000) is one such film. Here’s why.

- We tend to talk about Shakespeare in this weird, abstracted and academic way. Shakespeare becomes this difficult, serious, high-culture, nigh-impenetrable thing, that bears little resemblance to the actual works of Shakespeare. This is obviously in part because of the backwards way Shakespeare is taught in schools – where you have to read the play line-by-line before you’re allowed watch a film of it – but also because people who like Shakespeare are snobs who want to maintain the image of Shakespeare as this difficult, high-culture, nigh-impenetrable thing. I saw the Royal Shakespeare Company’s production of Cymbeline broadcast in the cinema, and a man glared at me because I laughed at all the jokes.

- Because Shakespeare is funny and silly and great. He wrote plays for mass appeal, to be enjoyed by all classes of society. The reason they are difficult now is because they’re very, very old, and language has changed so much in the meantime. That, inevitably, creates a gap, but treating Shakespeare with this absurd degree of seriousness widens the gap even more for no reason at all. I don’t really believe in high and low culture, but if I did, Shakespeare wouldn’t be in the high category. “Some are born great, some achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon them” is a dick joke. Titus Andronicus is an Evil Dead-style splatter comedy. Hamlet opens with some guards seeing a ghost and saying to Horatio that he should talk to the ghost because he’s been to college, which is objectively hilarious.

- Hamlet is my favourite Shakespeare play, but like a lot of Shakespeare, I think people take it too seriously. He’s played by actors who are too old, who deliver his soliloquies like they’re philosophical lectures instead of cries of pain. Hamlet is a very sad, screwed-up kid, whose modern descendents are The Catcher in the Rye or The Graduate or any legion of introspective teen movies and YA novels. Hamlet comes home from college to spend his time sneering “you’re not my real dad” at his stepfather and putting off important stuff so he can watch plays and go to the cemetery to touch skulls, which is definitely his period’s equivalent to putting off important stuff to watch TV and play video games. The language in his soliloquies is beautiful, but the sentiments are straight out of an emo kid’s diary, alternately furious with himself and lashing out at the world. He’s depressed (“How weary, stale, flat and unprofitable, seem to me all the uses of this world!”), self-loathing (“But I am pigeon-liver’d and lack gall”) and really hates his mam (“Frailty, thy name is woman!”). Maybe nothing has ever so beautifully summarised the contradictions of teenage feelings than Hamlet saying with total sincerity, “But break, my heart; for I must hold my tongue,” right after insulting Claudius right to his face.

- So I was really excited to watch Hamlet (2000). It’s set in modern times but uses the play’s original language, just like Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet, which is wonderful. It stars Ethan Hawke, who was thirty when the film came out, with Kyle MacLachlan as Claudius, and I love Kyle MacLachlan. I figured that, much like Romeo + Juliet was like a teen movie, Hamlet (2000) would be like one of those 1990s twenty-something slacker Gen X films, like Clerks or Reality Bites or Singles. It sounded like exactly the kind of adaptation of Hamlet I would make.

- If you just watch films casually, you probably don’t think a lot about what the director does. Writing and acting are easy to identify as elements of a film, but direction is something a bit more slippery. I first really thought about what the director does when I was sixteen and got really, really into The Social Network, the film where I learned how to see all the moving parts, and how seeing all the moving parts can contribute to your experience of the whole. I thought about shot composition and colours and camera movements and editing, and I could probably talk for twenty minutes about the scene where Eduardo takes two beers out of the fridge and then Mark gets his own, but in lieu of that, here’s Jamie Bell talking about it for 54 seconds:

- But before that, I only really thought about the director’s job in terms of telling the actors what to do, and maybe casting. On those measures, Hamlet (2000) is brilliantly directed: Ethan Hawke is close to perfect as Hamlet, Kyle MacLachlan is really good, Bill Murray is Polonius, which is great, and Julia Stiles does a good job as Ophelia. But the director has other jobs besides hiring good actors, and Hamlet (2000) makes a mess of a whole bunch of them.

- Firstly, some good points: making Hamlet a film student is really smart, because it allows the meta elements of the play to work in a different medium – play-Hamlet is really into plays, film-Hamlet is really into films. Turning some of Hamlet’s soliloquies into pretentious little films that he makes and watches over and over is great. Having him give the “to be or not to be” speech in voiceover while he wonders around a video rental place looking absolutely wrecked is probably the most sincere attempt to capture Hamlet’s depression I’ve seen on screen.

- The best is when he watches Rebel Without a Cause and gives the “what’s he to Hecuba?” speech, that in the play is about a visiting actor, about James Dean, which is probably the moment the film most earnestly engages with Hamlet as part of a tradition of young adult angst, and it made me smile really hard.

- It also does a pretty good job with Ophelia. We’re allowed see her frustrated and depressed in a way adaptations sometimes deny her. Ophelia’s tragedy perfectly mirrors Hamlet’s – her father is murdered by someone close to her, and then she, unlike Hamlet, really does go mad – but sometimes adaptations treat her as a prop in the same way the characters in the play do. I like the scene in the film where Polonius tells Claudius and Gertrude that Hamlet is in love with Ophelia, because Ophelia is visibly angry and tries to grab Hamlet’s letter away from him. When it becomes clear he won’t listen to her, she imagines drowning herself in the pool.

- But the film also makes a bunch of completely stupid decisions for no reason. The most bizarre: giving Horatio a girlfriend. A girlfriend character is written in and then given absolutely nothing to do, except occasionally stand next to Horatio while he’s talking to Hamlet. She’s supposed to be a genderswapped version of Marcellus, a minor soldier character, but they cut the most important scene that Marcellus has anyway. The only possible reason that I can think of for this is to make sure nobody thinks Horatio is gay, which, I mean, is stupid and terrible on its own terms, but is mostly completely pointless because Ethan Hawke and the guy who plays Horatio have no sexual chemistry whatsoever. They’d already zapped all the homoeroticism from Hamlet without needing to write in Horatio’s girlfriend, so it just seems like rubbing it in at this point, like when Star Trek (2009) gave McCoy an ex-wife just to clarify that EVERYONE IN SPACE IS STRAIGHT, DON’T WORRY.

- Hamlet (2000) has the blandest dramatic score I’ve ever heard. It plods along endlessly and is completely at odds with the best parts of the film, namely, Ethan Hawke being upset. Here are just some of the things that could have made a better soundtrack:

- Nine Inch Nails

- Grunge

- Eighties new wave, á la a John Hughes movie

- British post-punk

- Literally anything an angst-ridden teen might have listened to alone in their room

- The score is by Carter Burwell, who has done some of my favourite scores, especially his work with the Coen brothers. But the Coen brothers are able to integrate what might sound like pretty traditional dramatic scores in ways that don’t undercut the humour. In this film, the score overwhelms any other indicators of tone: at Ophelia’s funeral, Hamlet is bragging about how he’d eat a crocodile for her, and that’s at least sort of a gag, if a sad, bittersweet one. But there’s this bland score that’s been at peak seriousness for an hour and a half, and it robs the gag even as it fails to make the moment emotional.

- But mostly it plays when Hamlet is walking around, looking sad, and it makes those scenes a thousand times less interesting. Saying a film has a boring score sounds like a really abstract complaint, but the score has a huge effect on how the film feels. A great score can elevate a scene, like the running on the beach in Chariots of Fire or the shower scene in Psycho, and by the same token, a bad score can suck all the life out of a scene. I don’t mean a bad piece of music, necessarily, but a piece of music that doesn’t work with the film on an emotional level. Hamlet (2000) has the most generic dramatic score you could imagine, and so it not only fails to make me feel something, it makes me feel less than I otherwise would.

- If someone who knows about sound editing would re-cut those Hamlet-walking-around scenes with some angsty teenager music, I’d really appreciate it.

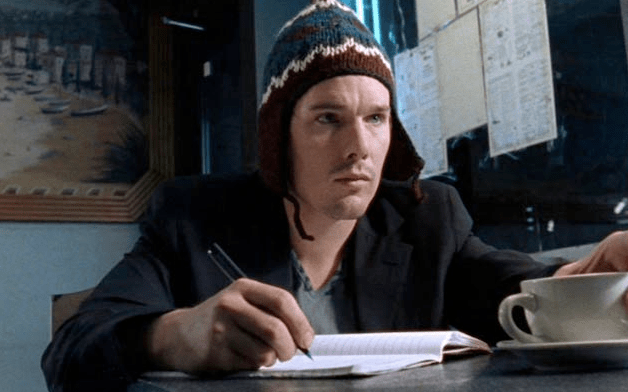

- There’s this hat that Ethan Hawke wears a lot in the film:

- Most of the time this is fine. I like it a lot, actually, certainly more than the blazer he wears so much despite being an unemployed twenty-something who hates authority and business. (In the film, Claudius is a businessman, rather than a king.) I assume it’s supposed to evoke Holden Caulfield’s red hunting hat, though I might be looking for things that aren’t there.

- But when Gertrude tells him to take off his mourning clothes, he’s wearing the hat. And a red polo shirt and orange sunglasses. I don’t think about costumes much, but I don’t think the people who made Hamlet (2000) thought about costumes much either. There doesn’t seem to be any kind of coherent idea behind Hamlet’s clothes. It seems obvious to me that you would dress Hamlet in a lot of black, but short of that, he seems like a guy who would be into counter-culture? Like he’d want to dress in a way that would piss people off. Maybe they were going in that direction by making him look all rumpled all the time, but he still looks like a very rumpled businessman in a funny hat. He doesn’t look like a film student, or the kind of guy who would have a breakdown watching Rebel Without a Cause, or the kind of guy who would watch videos about Buddhist philosophy (which, in this film, he does). But it’s not like they’re subverting anything with his outfit either, because his outfit doesn’t really give a lot of cultural signifiers – he just looks like a guy who got dressed in a hurry. I’d call it a wasted opportunity, but because film is a visual medium and we spend most of our time looking at Hamlet, it’s actively weird and confusing. But short of all of that, surely in the scene where they tell him to stop wearing black all the time, he should be dressed in black?

- The reason I was excited to watch Hamlet (2000) is I wanted to see Hamlet the way I see it in my mind’s eye: as a story about a sad young man who feels isolated, depressed and overwhelmed, who hates himself and fucks things up and who can’t find it in himself to take action. I saw Kenneth Branagh’s Hamlet in secondary school, and I hated it. I hated seeing Hamlet – back from university for his dad’s funeral – played by someone who, to me, seemed so old. (Branagh was thirty-six when it came out, but he looks every second of it and older, especially with the beard.) I hated how epic it made his soliloquies seem, especially the one where the music swells while he stands on a mountain. Shakespeare is serious business, and that means elevating Hamlet’s problems to serious, grown-up ones, not taking his feelings seriously on their own terms.

- We watched the Branagh Hamlet at school, because it’s the one that keeps all the lines from the play – even that weird speech about how terrible child actors are – and the way we teach Shakespeare means having all the lines makes something a better adaptation, even if the spirit of the thing falls through the cracks.

- But Hamlet (2000) misses the spirit of the thing, too, without any of the mitigating circumstances a more traditional adaptation might have. Ethan Hawke is brilliant, and plays Hamlet as I’d want him to be played, but everything else in the film does its best to drown him out. Shakespeare is serious business. In Romeo + Juliet, Baz Luhrmann manages to make something really fresh and unique that is really thoroughly its own thing. Hamlet (2000) never quite gets out from under the weight of what it thinks a Hamlet is supposed to be like. And Hamlet, we’ve convinced ourselves, isn’t supposed to have Nine Inch Nails on the soundtrack.

2 thoughts on “Notes on Hamlet (2000)”