This article is part of the Double Features series, which pairs great films that go great together. Check out previous installments here.

Hey there. It’s been a while.

I write about film and TV all the time. In Current Affairs or Crooked Marquee or Cineaste, for lectures and conference papers and podcast recordings. Sometimes I get paid, sometimes I don’t, but it is (at time of writing) the closest thing I have to a job. When Dean and I started The Sundae eight years ago, I would have said that was an impossible dream: ungraspable, barely glimpsable. Distant to the point of unreality.

I’m glad that it’s come true, of course. But there can be something alienating about it: I only write what I want to, but even to get paid the small-to-medium bucks, I have to shape my ideas around news pegs and audience expectations. When we started The Sundae, the only thing between me and the page was me (and Dean, thank God). And I didn’t have the time or space to decide what I wanted to say was neither clickable nor important – I had to write something new every fortnight, and, for reasons still unknown, everything we wrote was many thousands of words. Being a (semi-)professional is a dream come true, but there is a value in amateurism. Amateur, from the French: “one who loves, lover.” I don’t want to be such a professional that I cease to be an amateur.

When you move away, you still visit home. And as the internet transforms into a graveyard of bots and private equity, The Sundae only feels more and more like my online home. So let me say what every wayward child says and almost always means, even if they don’t follow through: I promise to visit more.

Let’s recommend some double features.

My Cousin Vinny (1992) / Married to the Mob (1988)

I watched both My Cousin Vinny and Married to the Mob for the first time earlier this year. I made it a double bill in large part because in my hazy second-hand impressions, they were basically the same movie. In fact, they have almost nothing in common, but make for a great double feature for the simple reason that they’re both balls of fun.

For reasons I can only attribute to internalised Italiophobia, I assumed cousin Vinny would have mob connections. Not so. My Cousin Vinny is basically Legally Blonde if instead of the protagonist being underestimated for being a feminine blonde woman, they were underestimated for being a working-class Italian-American guy from Brooklyn. Joe Pesci is wonderful in the role, finding an unexpected middle path between the Pesci of GoodFellas and Home Alone. (It’s a role he was sufficiently taken with to release an in-character album six years later.) Marisa Tomei, though, is a glittering Catherine wheel. She deserved that Oscar, and don’t let anyone tell you different.

Married to the Mob, meanwhile, is one of the screwball noirs that Jonathan Demme made his signature in the 1980s. It could be a dark drama about a former mob wife trying to restart her life, if it wasn’t wacky as all get out. Michelle Pfeiffer is irresistible in the lead, a beaten-down mother trying to give her kid a life not soaked in blood. Matthew Modine is the FBI agent sent to trail her, and he is – and I do not say this lightly – an absolute cutie patootie. If Pfeiffer is Married to the Mob’s noirish heart, Modine is its screwball one. So of course they’re meant to be.

Risky Business (1983) / Can’t Buy Me Love (1987)

Risky Business and Can’t Buy Me Love are both 1980s teen movie classics about paying someone to be your girlfriend. But they are, tonally and politically, the total inverse of one another. One is a dark satire about Reagan’s America. One is a goofy teen romcom. Both are a total blast.

In Risky Business, Tom Cruise is a high schooler in the wealthy suburbs of Chicago, a member of the Future Enterprisers club and, if his dad has anything to say about it, a future Princeton student. At home while his parents are on a trip, he ends up connecting with a sex worker, having his place robbed, and rolling his dad’s Porsche into Lake Michigan. When he finds out the cost of repairs, nobody has ever had less of an option to not become a pimp. It has both a scene where Cruise and the girl have sex on the subway while In The Air Tonight plays and does the getting-everything-back-perfectly-before-your-parents-get-home trope. It’s a masterpiece.

Can’t Buy Me Love takes similar narrative terrain and plays it light and breezy. Patrick Dempsey blows all the money he’s been saving from mowing lawns all summer to pay the most popular girl in school to be his girlfriend for a month. Dempsey’s Ronald is both a stunningly bad person and extraordinarily unlikeable: none of his friends should ever forgive him for anything he does in this movie. But Can’t Buy Me Love is so classically made that I couldn’t help but punch the air when he got the girl.

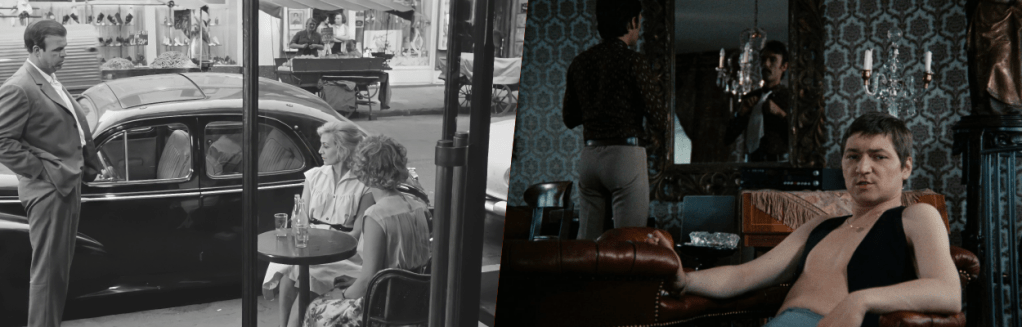

Le Signe du Lion (1962) / Fox and His Friends (1975)

Le Signe du Lion is a film about a rich man who does not know how to be poor. But poor he becomes. You become intensely aware of every penny, shouting in anguish about him buying a baguette and way too nice cheese. Then eventually he can’t muster up a Franc for a basket of gone-off fruit that they’re going to throw away. It feels like The Tramp’s origin story: the explanation for why the Tramp is such a fancy man, despite his circumstances. It’s a film about how poverty is self-perpetuating, spiralling, coiling like a vise. Anxiety twisted my stomach to pieces.

Fox and His Friends is almost the inverse of Le Signe du Lion, but it didn’t untwist my stomach any. Fox (played by director RW Fassbinder) is a working-class gay man who wins big on the lottery. Like how the gentleman in Le Signe du Lion doesn’t know how to be poor, Fox has no idea how to be rich. His new boyfriend is from a wealthy family, and makes out like he’s helping Fox – sweet, earnest Fox – use his money well, integrate into upper-class circles. Really, he’s bleeding him dry. It would be easy to tell this story with a satirical, acidic tone, but instead it’s devastating, unadulterated tragedy. It’s a film whose heart is as open and vulnerable as Fox’s, but it cuts as sharp as his so-called friends.

The Tall Target (1951) / Time After Time (1979)

The Tall Target is about John Kennedy attempting to foil a plot to assassinate Abraham Lincoln. Time After Time is about HG Wells chasing down Jack the Ripper. Only one of them involves time travel. Take a guess which one.

Xanadu (1980) / Grease 2 (1982)

I like Grease as much as the next guy, but that’s for normies. If you like Grease but like a bit of chaos in your life, check this shit out:

Grease 2 is a wicked funny genderswapped parody of Grease that has the crowning gag of being an official sequel to Grease. Michelle Pfeiffer plays the John Travolta role, and Maxwell Caulfield from Dynasty is the geeky British exchange student. (You can already work out who the mysterious motorcyclist Cool Rider, with whom Pfeiffer is enthralled, turns out to be.) It’s ridiculous and delightful. Every song in it is both hilarious and a bop. We’re Gonna Score Tonight? Do It For Our Country? Reproduction?! Why are we still living a world where I have to explain that Grease 2 is good, and not a world where the consensus is that it’s better than the original?

Xanadu, meanwhile, is set in a world of audaciously gaudy wipes and Electric Light Orchestra bangers. Olivia Newton-John plays a muse who begs her father Zeus so she can come to earth to help a failing artist achieve his life’s dream, nay, his destiny: opening a roller disco with an elderly Gene Kelly. Not a single film critic understood this in 1980, but dancing on roller skates is pretty much the best thing you can capture with light on film. It’s why Heaven’s Gate rocks. It’s why Roller Boogie rocks. And it’s why Xanadu rocks.